Читать книгу A Life of My Own - Donna Wilhelm - Страница 13

ОглавлениеExodus to Arizona

Remembering

In the 1950s, Americans avidly read newspapers and listened to the radio; nearly everyone watched popular TV shows. In 1956 the United States Supreme Court ruled illegal segregated busing in Montgomery, Alabama, and the SS Andrea Doria sank off the coast of Nantucket. The NY Yankees won the World Series, and Marilyn Monroe married Arthur Miller. Elvis Presley appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show, and his hit single “Don’t Be Cruel/Hound Dog” made number one on America’s music charts. Also notable that year, I graduated from E.B. Kennelly public school in Hartford as salutatorian of my eighth grade class. June 1956, how did a girl who feared the spotlight manage to deliver a graduation speech about patriotism to hundreds of people staring at her from the audience? She pulled it together, gave the speech, and the rest was a blur.

Although my transition to Bulkeley High School must have been challenging, I forgot most of the details, except for one event—the summer of 1957—that changed my life.

•

Don’t Trust the Mythmaker

“Yoo-hoo, it’s me!” Edith, waving both arms in the air, stood next to her 1950s Ford wagon at the bottom of the driveway. “Is anyone there?” she hooted. Edith didn’t believe in giving advance notice about when she’d show up in Hartford. That year, she auspiciously arrived at the beginning of the summer.

Poking my head out the kitchen window, I shouted back, “It’s just me here!”

Edith switched from dramatically waving to aggressive pointing at the wagon.

“Okay, okay … hold your horses,” I mumbled, trekking across the kitchen, down the stairs to the back door and across the lawn to greet my sister. Edith’s visits irritated me because they generally meant I’d be at her beck and call. She behaved like “Free Spirit of the Desert,” a nickname she was given by Hartford relatives who’d never seen the desert but fantasized about it. She dressed like a not-so-young Hopi maiden in ankle-length, pleated broom skirts or long-sleeved buckskin dresses, arms and chest draped with Old Pawn—antique Indian turquoise and silver jewelry. Around her waist she wore a heavy silver concha belt.

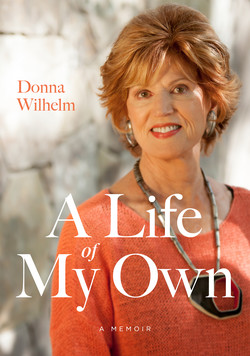

Edith, “Free Spirit of the Desert,” 1958

Edith’s turquoise skirted bottom was sticking out the wagon’s open tailgate. “Help unload!” came a muffled order that I pretended not to hear. The car’s exterior was encrusted with the grit of 2,500 miles of Southwest desert sands, Rocky Mountain red dust, prairie rainstorms and New England mud. I peered through the grimy side window. Usually the wagon arrived fully packed. This time, there were no stacks of Arizona Highways magazines or boxes full of prickly pear cactus jellies. Just Edith’s leather suitcase and her thin bedroll wrapped around a sleeping pillow wedged behind the front seats. The back seat, down flat, was littered with empty paper bags—nothing new about that. At rest stops and parking lots, Edith typically fed herself from sacks of canned food and dehydrated meals packed at start-up, and she took her naps in the wagon. Free Spirit didn’t believe in wasting money on motels or buying meals at roadhouse restaurants.

“Time to hose down the wagon.” Edith’s bottom emerged and the rest of her stood upright. I’d learn that Edith took better care of that car than she did the people in her life. Gathering up the accordion hem of the broom skirt, she tied it into a fat knot high on her hip, a way to proudly show off the long legs that, unlike much of her body, had not been scarred in that accident years ago.

Edith handed me a big sponge. “Scrub it good,” she ordered and pointed to a stack of frayed towels on the floor below the passenger seat. “Use them all!”

While I scrubbed and sweated, Edith poured cool water from the hose over her legs as if she had nothing else on her mind. We were mismatched in age, looks, and behavior. Edith and I didn’t have much in common. Until—

“Donna, you’re fourteen years old now, pretty grown up.” Edith suddenly stopped hosing. “Isn’t it time to cut off your long hair?” That got my attention. “If you come back to live with me in Arizona, you can have a whole new life.”

I couldn’t see Edith’s eyes, hidden behind the tinted glasses that she wore day and night.

“Think about it—freedom and independence!” Edith untied the broom skirt and let it cascade over her damp legs. “You can be a star at Sunnyslope High with Reggie!”

How did the sister I saw only once a year, with whom I’d never shared personal stuff, know that I secretly yearned to be a free-spirited woman?

Edith and I teamed up for a brilliant sales pitch to Mother and Dad. Edith made eye contact with Mother and jabbed at me. “Donna will finally learn how to take care of herself!” She assured our parents that, under her guidance, I’d make a healthy adjustment to desert life and enter my sophomore year at Sunnyslope High School with my cousin Reggie. Remarkably, they agreed to everything. I’d leave Hartford and drive with Edith to Arizona.

That night in my bedroom, I thought about what I knew and what I didn’t know. Reggie had red hair and lots of freckles. We were the same age. Hartford relatives gossiped about our ages being a “strange coincidence?” But what was coincidental about that? I wondered about the car accident that ended Edith’s future as a concert violinist. What did it do to Edith’s mind? Carl, according to Aunt Mamie, was a “real good dancer.” In their desert home, did he and Edith twirl around in their house doing fancy dance steps? If I went to live with them, would I truly become liberated and turn into the free-spirited woman I longed to be?

Mid-June 1957, the wagon was packed and the back seat flipped down to receive our supplies. Mother shoved an insulated aluminum chest into the car. It was filled with Polish dill pickles, ham sandwiches, potato salad, and thick slices of poppy seed cake. “Eat good for couple days,” she said.

Wedged next to the cooler was Edith’s large, leather suitcase that held her Hopi style wardrobe. My much smaller Samsonite was only half full, Edith having culled my Connecticut clothes. “We’ll get you all new outfits in Arizona,” she promised. By special concession, I was allowed to take my plastic bin of art supplies and one square cardboard box filled with my drawing notebooks. The so-called free space in the wagon was only sufficient for two sets of rolled up bedding. Little did I suspect that most nights we’d be sleeping crunched up like stowaways in the wagon.

On the awning-shaded porch, Mother and Dad stood together and watched their two daughters leave them. From the passenger side, I waved and attempted to stop the unexpected tears that blurred my vision. Hania and Juzo were holding hands, something I’d never seen them do before. In the driver’s seat, Edith backed the wagon out of the driveway and shot up a cursory wave. She made a sharp turn, and the wagon lurched onto the street. The figures of our parents grew smaller and smaller as 360 Fairfield Avenue disappeared from view. Not until much later did I acknowledge the conflicting emotions I felt that day: resignation that I would never again walk through the glass-paneled front door of Boarding House #2; and anticipation about my liberated future.

How many days and nights did it take road warrior Edith at the wheel of the wagon and me in the passenger seat to drive 2,500 miles across America? I had no idea. My assignment from Edith was to learn how to read US roadmaps so that I could track all the tourist attractions—so that she could bypass every single one.

Carl and Reggie were left to wait and guess when we’d arrive. They got only erratic reports from Edith shouting in public phone booths next to highway gas stations. On impulse, she’d call home and come clean—about where we were, that is. Only once, when we began to smell really bad, did Edith rent a room so we could take showers.

“Almost there!” Edith poked at me slumped and snoozing in the passenger seat. I sat up to views of flat and arid landscape, interrupted by Saguaro cacti, clusters of other desert plants and distant surrounding mountains. Driving past isolated homesteads, there were no boundary fences. Who owned what land was revealed by painted family names on hand-hewn mailboxes atop wood or metal posts along the road. Desert craftsmen apparently got inspiration from local lore. Giant scorpion bodies, tubular Saguaro cactus, Hopi rain fetishes and cowboy paraphernalia decorated wacky mailboxes big enough to hold family mail, daily newspapers, and bulky Sears Catalogues. During my year in the desert with Edith, I’d meet desert folks who were as quirky as their mailboxes.

Suddenly the wagon swerved off the road, bumped down a rocky driveway and halted. Flinging open the passenger door, I staggered out. Heat of at least 115 degrees blasted me like a wide-open furnace. Edith was immune to heat. Maybe dressing like a Hopi maiden in long-sleeved buckskin served both as mythical allure and as sun protection. Leaning on the horn, Edith sent obscene hoots into the desert silence.

Within seconds, Carl and Reggie rushed from the house, he as tall and skinny as she was short and plump. At most I’d seen Reggie four times in my life on the rare visits when Edith “tolerated” her company for a trans-America road trip. Having stolen Edith three decades before, Carl never returned to face Mother in Hartford. Not that I blamed him. We met, for the first time, in that desert driveway.

“Glad you’re home.” Carl’s quiet voice held little emotion. “We’ve been waiting.”

Reggie ran to the driver’s side window. “Mom, it’s good to see you.”

Edith pushed open the door, extended her long legs and stood up with no apparent effort or physical strain from the long drive. “You can help unload the wagon,” she said giving Reggie a brief hug. She didn’t bother with Carl and marched into the house, leaving the three of us behind to unload and scrub down the wagon.

My first impression of Carl would turn out to be accurate. He was patient, tolerant, and submissive to Edith as boss of everyone. Like mother, like daughter.

Reggie and I would be sharing the guesthouse over the garage, a space she’d previously had to herself.

“Take the back room, you’ll get a closet that way,” she said to me, leaving out a few details. The front room had a picture window with panoramic views of the desert and a direct-entry staircase. The back room overlooking the driveway had a window so small I could barely poke my head out, and the closet was merely a concave wall niche with no door.