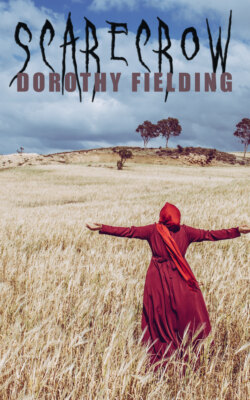

Читать книгу Scarecrow - Dorothy Fielding - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER I.

THE FARM OF THE GOLDEN GOAT

ОглавлениеTable of Contents

"JACK you're infernally lazy." Florence Rackstraw, hands on narrow hips, looked at Inskipp with an air of impatience. "Come along. The walk back will do you good."

It was now nearly five o'clock.

"I don't need to be done good to," murmured Inskipp, his felt hat tilted over his eyes. "I'm perfect."

"Same here," said Elsie Cameron drowsily. She was seated on the rocks beside him. "Don't let us keep you, Florence."

Florence shot Inskipp an angry look. He caught it and closed his eyes promptly. Her brother joined the little group of three on the Menton promenade.

"Well, haven't we dallied long enough in Babylon?" he asked, shifting a handful of stones to another pocket.

"In Bosio, you mean," chaffed Elsie. Honoré Bosio keeps the best cake shop in Menton, and the Rackstraws loved a good feed.

"Shake a leg, Inskipp," adjured Rackstraw. "I want to discuss an episode in Haroun with you."

Inskipp yawned. The two were writing a scenario. They were to share the profits of the film between them, and each talked as though they had a gold mine under their hats.

"Haroun is tired," announced Inskipp firmly. "Very tired. He won't be at home to visitors until to-morrow. Besides, Elsie and I are going to drive up to the farm with Norbury."

"You are an idler," said Florence with a nip-in of her thin lips, as, with a wave of the hand that looked angry instead of friendly, she led the way at a good pace along the Promenade du Midi to where the road started that would bring them after a three hours' ramble to Norbury's farm, La Chèvre d'Or, high up in the hills behind Menton. The four were his paying guests.

Elsie and Inskipp watched them disappear.

"There, but for the grace of God—" murmured Inskipp unctuously.

"I don't think any one should be as ugly as those two are," said Elsie. She spoke meditatively, objectively. She was an artist, and, incidentally, a very pretty girl.

And as though to give her another look at them, the brother and sister suddenly reappeared, walking briskly towards them. As usual, Florence Rackstraw was in the lead. She was very tall. Her head was too large for her bony body, and seemed to be all face, a face the colour of mottled mahogany. Her hair, straight as that of a mouse, was looped in two curtains over her ears and gathered into a tight little bun on her long, scraggy neck. Her eyes protruded. Her chin retreated. Her nose was hooked. Her mouth consisted of two thin, pale lines that slanted up to one side.

Her brother resembled her closely, with rougher features, and a still harsher voice. He, too, had her air of absolute self-satisfaction.

"As you're driving with Norbury, take these up for us, will you." The coats were tossed at the two before they could reply. Then the Rackstraws wheeled and strode off once more.

"You're treading on dangerous ground when you talk of ugliness to me," said Inskipp meaningly. And he certainly could not be considered handsome.

"But you're honest," objected Elsie at once. "You're straight, You can't be ugly when you look that. That's what I'm trying to get at, I think, that it doesn't matter if you look ugly, as long as you don't look as though you really were ugly—you yourself—in yourself."

"That's a bit difficult to grasp," said Inskipp with a grin that showed his strong teeth. "That's too much in Laroche's line for me." Laroche was a Frenchman, a writer of psychological studies, who was also staying at the Golden Goat.

"What I mean is that I think only ugly thoughts can make faces so plain. The Rackstraws look mean and malicious—and I think they are both those things."

She spoke with her eyes on the incredible blue of the sea in front of her. Inskipp altered his position to face her more directly. He was a young man, and Florence Rackstraw' had made a dead set at him when he had first come to the farm two months ago. He had drifted into a quasi intimacy with her before he saw his danger and struck out for safety.

"They're very intelligent," said Inskipp a trifle awkwardly. "Very clever."

"They are," agreed Elsie in a tone that said that that quality counted for little. "But they could be very dangerous, both of them."

"In what way?" he asked.

"I haven't the faintest idea," was the prompt reply. "I don't reason about people. I feel them. And never, never make a mistake," he finished with mock solemnity.

"Never when I dislike people. It sounds cynical, but it's true. It's only when I like people that I may be all wrong."

They were lounging on the Promenade du Midi, that broad walk that runs along the sea at Menton, sometimes with neither parapet nor railing to protect it from the water. A grand walk when the sea is rough, and the green waves come roaring in over the foundations of the wall. White wings were wheeling and circling over their heads. One gull, more adventurous than his mates, nipped the bread from Inskipp's fingers in his swift glide past, banked—a lovely flash of silver—and came back for more. The hot sun flooded everything. The air was cool and fresh. The sea ran in broad washes of deep blue and bright green. The sky was the true sky of Menton, high, and blue, and soft, and deep. The donkey and ponies, kept at a corner of the casino for children to ride, stamped a little. They were as bored as Inskipp felt. A few notes from the orchestra playing outside the casino reached them. It was all like a scene at a theatre, Inskipp thought, something which he watched, but in which he had no part. As for Elsie, she was at grips with a curious, a quite contrary feeling to his. It was as though something were trying to rouse her to a sense of the moment's importance. She got up, ostensibly the better to watch the gulls whirl overhead, in reality to give herself room. What was this sudden impulse which was sweeping through her as the gulls swept through the air around her—an impulse to fight and win the man beside her, a sudden awareness of powers within her which, if used—of qualities which, if shown—would draw John Inskipp to her side and keep him there. He was a lonely man. She knew herself to be his complement. Should she make him realise this? She could. She knew that she could. What she did not know was that the fate of Inskipp depended on that moment—that Atropos with her shears paused for a second to wait for her. Had she obeyed her innermost craving Inskipp would have been saved. But, unfortunately, Elsie came of a race of women who were won, not who did the winning. She told herself the truth, that she cared for him much more than he did for her. She flung off the odd feeling that the moment held some opportunity which would never come again—and turned to see a man hurrying towards them along the promenade.

"Here's Du-Métri," she said in a welcoming voice.

"Two-Yards" was the nickname of the Norburys' factotum. A tall wiry figure, he came swinging along the Promenade from the nearby Halles. "Ohé!" he hailed, and waved a long, lean arm. Elsie liked the man. Two-Yards was a character. She sat smiling as he strode up and made a jerky little bow. "Il padrone sends this message," he said, drawing himself erect. "Not to wait for him here, as he must go to Gorbio. He will have to pick you up at the old Carnoles Olive Mill."

Two-Yards looked as though carved from pliable teak, his features were so salient, his colouring so uniform and dark a brown. His lean, clean-shaven face was good looking, with regular features, and dark eyes that were at once keen and veiled. He knew every star that hung in the Menton heavens, and he knew their courses, the hour of their rising and the time of their setting. He knew all the flowers of the fields, and the birds in the woods, as he knew his own herds. Born in the hills behind Hyères, Two-Yards was steeped in Provençal legends and folk-lore. It was from him that Inskipp had first heard the legend of Haroun, the Moslem Corsair who had turned Christian for love of a captive maid.

"Are you coming up to the Mill, too?" Inskipp asked.

Two-Yards threw up his chin in sign of negation. He had still some purchases to make for the farm, and would follow later in the day in the farm cart. His eyes on the horizon, he stood a minute looking out to sea.

Leaning far out of a boat painted green and yellow, a fisherman was beating the waves with all his strength, and at the full stretch of his long arms.

"To drive the fish into the net," Two-Yards said in reply to Elsie's inquiring look.

"Is there anything you don't know, Du-Métri?" she asked him.

"Yes. I don't know who gives my Sabé her silk handkerchiefs," he said suddenly.

Sabé—short for Isabella—was his daughter. She was a flirt, and Du-Mari was a Spartan parent.

"Well, I must be off." And he took his cap off again, while Elsie laughed silently.

The two caught the next Gorbio bus and were whirled along to the old mill at its opening.

Green and cool and very lovely, the road wound past gardens where geraniums hung in thick mounds the size of cartwheels on the stone walls, or climbed half-way up the trunks of the palms, where roses and carnations filled the air with fragrance, where the bougainvillea covered walls and roofs with its magnificent purple. They got out at the Old Mill and sat down to wait for Norbury on the rocks which dot the entrance to the little hamlet. The ruined Maulesséna Castle was to one side, the great new sanatorium was hidden by a group of olive trees fifty feet high. Where they were sitting, they had pines on one side and palms on the other. It was typical of this corner of the world. The rustle of the palm fronds sounded like heavy rain in the breeze. Below them lay Menton looking what architecturally, as well as historically, it was—pure Italian, as it curved around the Gulf of Peace, a horseshoe of emerald and cobalt. Eastward, two lines of lavender and violet mountains carried the eye to Bordighera, whose houses glittered like dice on the farthermost spur of land. Up here, one even caught a glimpse of the Gulf of Genoa on the other side of the first line of purple hills, like a stroke of sapphire. To the west, the green ridge of Cap Martin ran an arm into the sea with one white hotel catching the light.

Elsie drew a deep breath. Things must surely come right between her and Inskipp in such a world. And if that was not to be, then beauty such as this can fill the heart like love. The sunshine flooded all her being, luminous and strong and vital.

She crumbled some of the earth between her fingers. "It's wonderful soil. You've heard, of course, of the man who, by an oversight, left his umbrella sticking in the ground hereabouts. When he went to look for it a week later, he found it a small tree in full bloom."

Inskipp laughed outright.

"Did Two-Yards tell you that one?"

"No. Mr. Norbury." Getting to her feet, she looked about her, her felt hat in her hand.

"I don't think there's anything in the world more beautiful, in its own way, than is this region." Her eyes were shining, her whole little face alight and glowing. It was a whimsical, irregular face under a mop of tawny hair that had streaks of red, like flames, in it.

"I suppose not." After a pause Inskipp added. "But it doesn't mean anything to me. Does it to you?"

"Mean." She was puzzled, and her transparent, candid face showed it.

He made a vague gesture. "It's lovely—as a set scene at a theatre is lovely. But it's not real—to me. Palms—they can't take the place of beeches. I'd rather look at an oak than an olive, any day—"

"And you'd rather watch rain than sunshine—is that it." she laughed. "Nothing like patriotism!"

But he was not laughing.

Inskipp's sallow face was a melancholy one. Something about it suggested the seeker who had never yet even caught sight of anything worthy of his search, the visionary who had never yet had a vision. In age, he was under thirty.

His brow was narrow and low, not the brow of a clever, or even of a well-read, man. His dark, deep-set eyes were his best feature; they were unsatisfied looking, but well cut and well opened. His nose was thin, with generous nostrils, his mouth also suggested generosity as well as firmness, his chin was dogged and masterful. Elsie's quick eyes had put it down correctly as the face of a dreamer; but Inskipp did not look at all like a dreamer who could not be wakened. You might fool him without any great difficulty, possibly, but most assuredly you would have to pay for it afterwards if he learnt the truth. He was under medium height and slenderly built, with a narrow chest which was the reason for his being out of England. A bad attack of pneumonia had sent him to Menton, and a chance stroll up among the hills had suddenly brought him, some eight weeks ago, to a low Provençal farmhouse. Twin cedars stood at the gateway—one standing for Prosperity, one for Peace. Its roof was of the red, fluted Provençal tiles, its garden hedges were of rosemary and juniper and lavender.

Inskipp had spelled out the farm's name on the gate, and wondered at it: >La Domaine de la Chèvre d'Or. Two-Yards had seen him, and promptly asked him to hold the gate open for a pig which was intent on double-crossing him. In the pig-hunt which followed, Inskipp, Two-Yards, the pig, and a tall, rangy man of middle age who swore heartily in English, all got thoroughly well mixed up. When the pig was back where he belonged, instead of where he wanted to be, the Englishman introduced himself as the owner of the farm, and asked Inskipp in to taste some of his new wine. Inskipp met the other guests who were staying at the place, and had promptly arranged with Two-Yards to fetch his things from below. He had not regretted it. The farm was simple, but it was cheap, and the scenery was magnificent.

Inskipp liked Mrs. Norbury, too. So did Elsie Cameron, who had been at the farm since early spring. She, also, had to spend the winter in warm and sheltered nooks, and the farm was securely tucked away alike from Bise or Mistral.

Norbury's yodel came ringing down the green valley above them. Inskipp answered with one of Two-Yards' strange shouts. Such a shout as the Provençal herdsmen give at dawn and at nightfall. A shout which has come down from the Phoenicians, said Laroche. It stirs the hearer strangely. Some old tumult of the blood beyond our present-day reason or understanding answers it. Elsie never listened to it without a feeling that the enemy tribes were at the stockade, that javelins were flying around her.

Norbury drew up his Ford close to them.

He was a big, sunburnt man in the early forties, with a pleasant enough but very non-committal face, out of which would come at times a glance, chill and keen as a north-easter.

They clambered in over bags of flour, sugar and salt. Then they were off.

"How's the marketing been?" asked Inskipp as they had to slow down for a herd of cows.

"So-so," was the reply. "They say the weather is going to break. Hope it won't, or it'll be a bad look-out for my oranges."

Norbury had not many oranges on his farm, but he overlooked no source of profit, and an orange-tree bears easily three thousand oranges in twelve months, and choice ones yield four times that.

It did not take long to reach his Domaine, or farm, and for a moment the three of them looked down at a sea of grey-green olives which hid the lemons and vines planted below them.

Norbury's chief source of income was from his lemon-trees. The Mentonais claim that Eve's last act when leaving Paradise was to pick a lemon to carry with her. She decided to give it to the most beautiful country which she and Adam should find on their wanderings. When she came to Menton, she flung it on a terrace, telling it to grow and multiply and turn the land into another Garden of Eden, which—according to the legend—it promptly proceeded to do.

Norbury called for a couple of the farm hands to help him unload the car, while Elsie and Inskipp walked round a corner to the house. As they did so, a good-looking young couple came sauntering up to the open door. The woman in front, with something very graceful, though weary, in her gait. Edna Blythe always walked like that, though she never seemed to go farther than the nearest sunny corner. She was a tall, slender woman, not pretty, exactly, but with something about her rather sad, very bored-looking face that suggested that she could be pretty if she chose. She was fair, with fine brown eyes, and a low forehead. Her features were well cut. A straight nose, a small, curiously tight mouth which yet looked as though when relaxed it could be very sweet, an obstinate little chin, and a firm jaw. Her hands were nervous and suggested illness.

Her brother, who followed her in, was tall and fair, too. Otherwise there was no resemblance between them.

Mrs. Norbury joined them with one of her ginger cakes which she wanted to put out of doors to dry off. She rated Norbury sharply for letting the car cut across the grass. Inskipp sometimes fancied that her big burly husband was a little afraid of his dot of a wife, and indeed Mrs. Norbury could be very forthright and unbending at times. There had been that affair of the Italian count and the lady he called his wife just after Inskipp's own arrival. Mrs. Norbury had learnt from the young man himself that he and his companion were not yet married, though they intended to have this done soon. The car took the two down to Menton the same day, Mrs. Norbury driving, and looking calm and unflustered, in spite of the fact that the count and future countess on the back seat seemed to have turned into two geysers.

"If you tolerate a thing, you aid it," was her only comment on the matter, in answer to a chaffing remark of Rackstraw's, who thought her attitude distinctly comic.

She asked Inskipp and Elsie about Menton as she carefully set the cake level.

"It was very close," said Inskipp, "and very enervating."

"As always—" threw in Elsie.

"And as always," he went on, "full of Voronoff's patients, or would-be patients."

"We women score when it comes to old age," said Mrs. Norbury meditatively. "We accept it more placidly."

"Not while there's a paint-pot to be had!" retorted Elsie, laughing.

"A woman has to accept so much," Mrs. Norbury maintained, "that old age seems a trifle." She spoke bitterly. Her voice was bitter, too. But, then, Mrs. Norbury did not have a pleasant voice at any time. Over the telephone, that tester of tone, it sounded very hard always, and could sound distinctly grating.