Читать книгу Scarecrow - Dorothy Fielding - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER II.

INSKIPP HEARS OF MIREILLE, AND LEARNS

WHAT THE GOLDEN GOAT STANDS FOR

ОглавлениеTable of Contents

FOR Inskipp, the next fortnight was one of outward peace and inward battle. He won. At the end of the time Florence Rackstraw treated him as a very unpleasant insect, and Inskipp was glad. He had found it harder than he thought to get out of the atmosphere of the suitor in which Florence had very subtly wrapped him and all his words. He had had to be really rude at the last to cut the cord which, she insisted, linked them. Elsie had watched his struggles with approval, but with no overt help. She told herself that, as he had got himself into the false position, he must get out of it by himself, too. But when he was out, he was no nearer to Elsie.

One night, when the other men were off helping to drive some young bulls to Castellar, whence they were going to be sent to Arles and Nimes for the bull fights, he and Mrs. Rackstraw had sat talking on the verandah. Oddly enough, Mrs. Rackstraw had been Inskipp's secret ally in the struggle with her daughter. Inskipp had thought more than once that she had no love for either of her children. Had he known the story of her life with their father, and how much these two resembled that unpleasant gentleman, now dead and buried, he would not have been astonished. As it was, after Inskipp, beguiled by the singing of the nightjar in a nearby tree, and by Mrs. Rackstraw's words on companionship had drifted into what was practically a description of his ideal woman, Mrs. Rackstraw had said significantly:

"I know a girl who fits that description of yours, Mr. Inskipp. All but the loveliness, which you think means a beautiful soul—and that's Elsie Cameron."

Florence Rackstraw, who had slipped unnoticed into a chair in the corner, sat very still.

Inskipp was amused. How little people understood, he thought. Here had he been indiscreet enough to give a glimpse of his heart's ideal, and what he showed had been identified with Elsie Cameron Elsie was a nice girl, a very nice girl. He would be a lucky chap who would win her one day for his wife; but as to her resembling the dream creature he had described—Inskipp gave a suppressed smile, then he made for his own room. He wanted to jot down his impressions of the herd of bulls this evening as they had gone roaring, stamping, snorting down the valley. Just such an incident could have happened at the castle of Anna's father—Anna was the Christian maid who had converted Haroun to Christianity, said the tale. Inskipp had never up till now written anything, but he was bored at the farm, and boredom is the best incentive to writing.

He had worked for about an hour, when a knock came at his door.

In answer to his curt "Entrez," Florence Rackstraw came in.

"I've got something that would fit wonderfully into your film," said Florence. "It's in a book on Provence castles—an old French book that I picked up in Menton last time we were there. I've been reading it."

A week ago Inskipp would have made an excuse but she had altered—she had retired defeated, and he followed her without another thought to the large room which the Rackstraws used as a sitting-room.

"Light your pipe, and I'll get it," said Florence as she stepped on to her own bedroom. "Matches are on the mantel—" she called back. Her tone was friendly, though detached.

Inskipp strolled to the fireplace, where some logs of olive wood were still smouldering.

He suddenly picked up a photograph standing by the clock. He had never seen it there before. He had never seen it anywhere before. This lovely oval. This beautiful small head set so proudly on its slender shoulders.

He still had it in his hand when Florence came back.

"Isn't she beautiful? She's my greatest pal! And she wants to go into a convent when she has secured her divorce!"

"It's the loveliest face I have ever seen," he said slowly.

"And as good as she is beautiful," Florence said warmly. "I want her to come here. It would do Mireille good to have to interest herself in the affairs of this life for a while. She is too unworldly."

"Mireille." Inskipp repeated questioningly. What a charming name, he thought.

"Yes. Mireille de Pra is her name. Madame de Pra. She was married some three years ago, but she never lived with her husband. He had a fit as they were walking down the aisle after the wedding; he rolled right off the steps, they say—I wasn't there—and for a while they thought he was dead. But unfortunately he wasn't. For when he came round finally he was raving mad, and has remained mad ever since. Isn't it terrible!"

"It's a crime—marriage such as that." Inskipp was fairly stuttering.

"I have another photograph of her. Would you like to see it?"

Florence felt in a drawer and handed him a portrait as lovely as the other, if not more so, for it showed a figure as beautiful as was the face. It showed the same girl—she looked barely nineteen—in what seemed to be a convent garden bending over a great spread of Madonna lilies. Inskipp's heart contracted, and expanded, and did all sorts of queer things inside him.

He said nothing, only looked at the two photographs.

"She has to stay in the convent in Brittany for the present," Florence went on. "But, then, frankly I'm not keen on Harry meeting her. He isn't her sort at all, and it might spoil our friendship. I usually keep these photographs safely tucked away for that reason. He doesn't know about her, and—well, I don't see why he should. He may have left here before she comes."

She put the photographs carefully into a drawer. Then she showed him the book with the descriptions of the old castle that had interested her. Inskipp barely understood what she was saying, but he thanked her effusively, and, taking the book, went out of the room, his head in a whirl. He felt like a man who has most unexpectedly stumbled on a treasure. A sense of excitement filled him, an impatience for the weeks to pass till that wonderful creature should stand before him in the flesh as she stood in the photograph. He felt as though the world were a marvellous place, as though to each of us had been offered a ticket in a wonderful lottery. The feeling stayed with him next morning when he woke up. But as he dressed, and when he sat down to his writing, doubts began to rise. He told himself not to be a fool. Girls such as that one in the photographs would not give him a second glance. Or even one. He laughed aloud in scorn at his ugly, dull self.

"Glad you're in such a cheerful mood, Inskipp," said a voice behind him. "The fact is, I was wondering whether you would help me out again—just for the next few days. I don't like to keep the Norburys waiting."

Rackstraw had come in through a side door.

Inskipp took out his pocket-book. A bit over two hundred francs should settle Rackstraw's debt to the Norburys. Inskipp was anything but a wealthy man, but he had set aside a thousand pounds for odds and ends when he had invested the remainder of his money. So far, he had spent very little of it. Money could not buy happiness—could not prevent acute loneliness, for bought companionship is no companionship. Inskipp had tried that out thoroughly already.

"I'd ask the Norburys to let it run on for a bit," Rackstraw said, "but they're having a hard time to make ends meet, let alone lap."

Inskipp said that this was news to him.

Rackstraw made a little face.

"It wouldn't be if you slept in my room. Mrs. Norbury wants the money back that she put into the farm, and Norbury can't run to it."

Inskipp handed over the notes now, but he had an uncomfortable feeling that Rackstraw was meditating a further request for a loan. Something biggish. He fancied that Rackstraw had been trying to get up his courage for it for some days.

He slipped away out of doors. The orange trees were too compact and tidy for his taste. Inskipp preferred lemon trees. By the back door was a charming specimen. A sudden desire to paint it came over him. He could sketch in an amateurish way in water-colours, and he went indoors now for his sketching-block, and box of colours. He chose his pencil carefully, and set to work.

Not for him was the one-line of the real artist, but by patient work he achieved a very accurate drawing of the little tree. Its beauty grew on him as he studied it. Its airy grace, the delicate spacing of its fine leaves which decorate but never hide branch or fruit. Its shape as it grows older is much like that of a pear tree, but the abundant, daffodil yellow fruit hangs so clear of branch or leaf, that it, seems to be backed only by the bright blue of the sky, and against that sky the effect is enchanting.

Inskipp enjoyed the work. Unlike the writer, the artist, however poor, finds that if he is patient he enters into a life within life, a world within the world. Colours become more than something seen by the eye—they have a meaning—they have a magic—

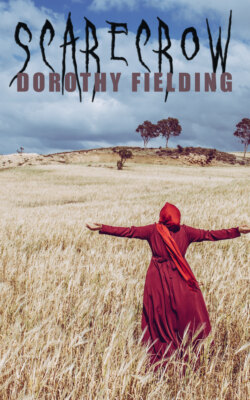

Inskipp decided to put in the kitchen door, the maize field with its tassels and the scarecrow that stood in one corner, and a tiny lemon sapling which grew at the base of the second lemon tree, with its little fruit the size of an acorn, but perfect in colour and shape, dotted like fairy lamps all over the slender branches.

"Tiens! You sketch? Well, perhaps?" It was Monsieur Laroche, sipping a glass of Chateauneuf du Pape. As for the local stuff, Laroche maintained that it was not wine at all, but merely vinegar in the making.

Monsieur Laroche repeated his remark. His mother had been Irish, and he spoke English as though born in Dublin.

"Why should I not sketch?" Inskipp asked, putting his drawing away.

Laroche had a way of making him feel as though he were under a microscope, than which there is no sensation more distasteful to a Briton.

"I agree that it is in character." Ah, there he was again I Laroche could talk by the hour on what was in a man's character and what was not.

Miss Blythe came towards them.

"Has the noon-gun gone yet?" she asked. They all set their watches by the cannon fired from Menton fort.

Inskipp thought she had a pretty but rather vacant face. She was very dull to talk to, very heavy in conversation, and she had a habit, which embarrassed him, of listening with her eyes rivetted intently on the speaker, as though she would never see him again, and the memory of each feature and of each expression might make all the difference to her own future.

The gun boomed. Miss Blythe set her watch, and passed on.

"What's her character?" he asked Laroche under his breath as the Frenchman stared meditatively after her.

"Ah!" said Laroche between his teeth. "That is the thing she hides with all her skill. But I have my ideas!"

Inskipp was amused. Poor quiet, dull Miss Blythe!

"I can't think what you see of interest in her," he said truthfully.

"I see a most uncommon sight," said Laroche almost sadly. "I see a person afraid of themselves. Yes, just that. Not, as I thought, merely afraid to show herself to others, but afraid of some weakness—or some impulse—in herself. I suspect drink," he said finally.

"Mind you," said the writer apologetically, "that is only a guess. Chiefly because of the choice of this farm. No temptations here. Mr. Norbury keeps no cellar. His eau de vie is only useful as an embrocation. The farm had its own still, a perfectly respectable farmhouse appurtenance in France, where every windfall finds its way ultimately into it. "I wish I could dear her up," he added, "but it might take years."

"How about asking her brother?" suggested Inskipp.

The Frenchman considered a moment, then he shook his head. "I think not. He is born a bully under his varnish of the public school. And, by the way, how he avoids saying what school he was at."

A sound of voices made them look up. Rackstraw and Du-Métri were walking together towards them. Mrs. Norbury was behind them.

"Another painter! Here's Du-Métri with a pot." Laroche stepped aside to avoid its swing.

"For the Golden Goat," said Two-Yards, with a gleam of his strong teeth, making for the gate, where he began to repaint the name. As he did so, he started one of his songs of which the refrain was:

Apres aco, su anac. (After which I left.)

Laroche listened to it with delight. He wondered what Mrs. Norbury would say if she could understand the words of the Rabelaisian old ditty.

Mrs. Norbury, as it happened, was thinking of the painting that was being done, not of the song.

"I do so dislike the farm's name." She looked at the gate frowningly. "I wanted to change it to Lou Lavandou, or Las Mimosas. Provençal names, too, both of them, but you can't change things in Provence. Not even though the last owner was gored to death in a field over there by one of his bulls."

"But the name wouldn't alter the luck, surely." Inskipp's voice was amused.

"It's supposed to be unlucky," said Mrs. Norbury shortly, turning back into the house, "but my husband doesn't believe in luck."

"I thought La Chèvre d'Or is a beneficent creature who guards the hidden treasures left by the Saracens," said Elsie, who, together with Rackstraw, had come out after Mrs. Norbury.

"And I thought he was the defender of Provençal relics, butting away the archaeologist who got too close to anything interesting," said Rackstraw.

"One of its duties, certainly," allowed Laroche. "That Chèvre d'Or is evidently in the pay of the Department of Public Works. But he has another side. A more mysterious side. He is also The Unattainable. The Impossible-to-realise. And to see that Chèvre d'Or is to die shortly afterwards."

"They would get that side of him from the Greeks, who settled all this part of the coast and built their temples and theatres here," said Rackstraw, who was an archaeologist.

"Yes, in many places he is Pan. But he is other things, too. A blending of many old superstitions." Laroche made a gesture as the luncheon bell sounded. "Unless you are a Provençal—and even then—it is better to leave the mysterious creature alone."