Читать книгу Beyond Truman - Douglas A. Dixon - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

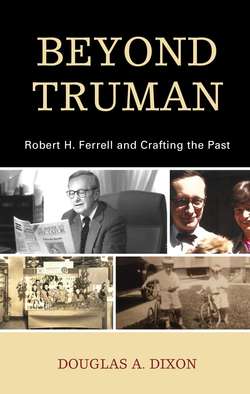

Robert H. Ferrell (1921–2018) earned the title “Distinguished Professor of History” at Indiana University in 1974. Some might honor him with a more colloquial moniker such as the Midwest’s best Ivy League storyteller. But in an era when the media emphasizes dramatic and overstated claims suggesting that someone is the best at anything will likely evoke skepticism, so it deserves explanation. Ferrell could claim to be the best Midwestern historian on any number of counts. He wrote or edited sixty books, many after his retirement; the writing continued into his eighties.1 The first volume, Peace in Their Time, came in 1952 and won top prizes at Yale and the American Historical Association. The most recent book, published in 2011, very likely showed a marked progression in subject focus in the eyes of postmodern critics—African American troops in the Great War, Unjustly Dishonored. Ferrell’s correspondence, however, reveals that his concern for others’ mistreatment did not come late in life.2 He also guided a record number of dissertations to completion as published books, perhaps seventeen at one count, and shepherded males and female students alike, despite a more Victorian-era view of women’s roles. On the basis of scholarship alone few Middle West historians of any stripe can best Ferrell.

The qualifier best could also attach to Ferrell’s omnipresence among colleagues, whether editing their work, founding or serving historical organizations, contributing as a highly sought-out publishing consultant, authoring a top-selling American Diplomacy textbook, and as importantly, serving as a friend and mentor to many in the field. The adjective best also may allude to a certain moral insight and behavior. Ferrell was an Eagle Scout, with a true compass that pointed the right way, in the Lincolnian sense, as God gives us the ability to see it. His moral rectitude flared in his role as historian as well as democratic citizen. U.S. presidents, senators, and military brass got the Ferrell treatment as did well-known fellow authors, academic or otherwise; David McCullough or Merle Miller are good examples of the latter. Ferrell called for President Clinton’s resignation after the pitiful dalliance with the well-known intern, and he had plenty of thoughts on Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower, and Richard Nixon. This best historian also found critical words for other notable figures, Collin Powell or Margaret Truman.

From another vantage point, former Ferrell students attributed their professor’s exceptionalism to the helpful, if paternalistic, attitude he displayed as one found his or her way into that sparse Ballantine Hall office on the seventh floor. Surrounded by books and dressed in a clean, iron-pressed pin-striped dress shirt, Ferrell always had the appearance of professionalism and that of a busy scholar, more often than not facing a manual typewriter, yet he always found time for students. A former student of his, presently serving as an executive associate dean at Indiana University’s School of Global and International Studies, shared an apt illustration: One day I relayed the difficulties of student monies arriving after the semester started, which each year put me in a probationary status with finances. Professor Ferrell picked up the phone, called the Bursar’s Office, and solved the problem on the spot, then turned to me and said, now let’s focus on your interest in history. The present author can attest to the enormous energies Ferrell expended across three independent-study history courses and the marked-up papers to prove the point. These experiences are hardly uncommon. Into the present decade, the Indiana University Alumni Association continues to find him a “favorite professor” in polls conducted and anecdotes shared.3

In addition to his respected professional status, or better said, infusing it, Ferrell represents the Midwest in birth, career attachment, and in many ways, outlook. Born in a Cleveland, Ohio, hospital May 8, 1921, he and a younger brother, June, and parents Ernest Sr. and Edna, faced the volatility rooted in the economic swings of his age, living at times near urban environs, then on a family farm (a savior from bank collapse), near Custar, Ohio. As with perhaps the majority of heartland faithful Americans, the budding Bob Ferrell attended a Methodist church in his early years. Teachers of the Good Book, family and friends, inculcated a lifelong, evangelical orthodoxy that continued with extended family, including endless correspondence with Aunt Ocie. Ocie, a sister of Ferrell’s mother, alongside Uncle Mark, spread the Gospel as missionaries in China, and the message was rarely lost on Ferrell in the letters passed to him. Ernest Sr. and Edna made the evangelical tie indelible by assigning the middle name Hugh to their son, the namesake of a missionary in China, Hugh Hubbard, a cousin. One might say, Ferrell’s genealogical roots grew from white, Anglo Saxon, Protestant soil (the derided WASP to many postmodernists), and, by extension, he consciously or otherwise internalized Midwest breadbasket conservatism, that of close family ties with fealty to faith and farming. Ferrell grew out of the family shell to become more iconoclastic in outlook and values than his progenitors.

The zig-zag in other-than-Midwestern birthright came twice for the future historian, and these were significant changes of scenery. Ferrell packed his bags for the Second World War after three years at Bowling Green State University (1939–1942), a school just a few miles from his home at the time. The war years would expand the horizons of Ferrell, which led to momentous decisions afterward, namely the focus on history and away from music education. The second Midwest variance came with acceptance to Yale, the Ivy League school in New Haven, Connecticut, and history graduate studies (1947–1951). Much will be said about this fortunate connection, and it certainly colored his world, to his benefit. New Haven trumped a Bowling Green pedigree, and Ferrell capitalized on the former. After graduation, the Yale alum with distinction unhappily held a one-year appointment to an Air Force intelligence job in Washington, D.C. The Pentagon work reintroduced the war veteran to the Washington-based bureaucracy he came to abhor as part of his service. By the fall of 1952, Ferrell found his way back to the Midwest—this at Michigan State College (later university) by means of Yale mentor Samuel Flagg Bemis’s former school chum. The move permitted the final leap to Indiana’s flagship state university the following year, another Yale network advantage. This is where Bob Ferrell found fertile ground, in one of those “I” states that Midwestern outsiders can never keep straight (not Illinois or Iowa), but in some ways very similar to them along with Ferrell’s native Ohio, thus, the title the Midwest’s best Ivy League storyteller.

NOTES

1. Robert H. Ferrell, “Contemporary Authors Online,” Gale, 2018. Biography In Context, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/H1000031397/BIC?u=loc_main&sid=BIC&xid=2d7b177a. Accessed October 2, 2018. Ferrell’s Unjustly Dishonored, published in 2011, is not included in the citations.

2. Letter to Murf, Marion, Karl and Stephen, February 25, 1952, Box 84; letter to Bob and Kit, July 12, 1953, Box 44; letter to Chris and Bob, September 15, 1953, Box 44; All correspondence referenced is housed at the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, unless otherwise noted. Letters cited are from Robert H. Ferrell unless otherwise identified.

3. “Favorite Profs,” Indiana University Alumni Magazine (Fall 2013), 11.