Читать книгу The Boys of '93 - Eamonn Coleman - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

SOME BOY

by Maria McCourt

Red, white. Silver. That’s how I see it through his eyes as he leaves the shores of Lough Neagh. The red and white of Derry. The silver of the Sam Maguire. Blue, grey, green, black … red, white. Silver. The blue of the lough, the lane from his bungalow, up through the fields to the asphalt road. To Croke Park, boys … Croker. The silver of the Sam Maguire. The cathedral of Gaelic football awaits the ‘third Sunday in September’ faithful but today is just the third Saturday and the pilgrimage has yet to be made.

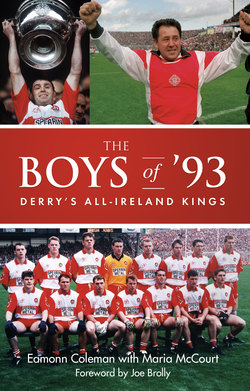

He is Eamonn Coleman, my uncle, my godfather and friend. But to them he’s the Little General, the Boss, the Leader, the Man. For only the second time in the county’s history – and the first in thirty-five years – the senior footballers are in the All-Ireland Final, the Championship’s ultimate stage. By his side is his son Gary, a key player in this ’93 team. The warm words from his aunt as he leaves: ‘Don’t come back here without Sam’. She’s not renowned for her sentimentality, my grand aunt Eliza Bateson, but she has been here in their South Derry home since Eamonn was a boy.

‘She came to look after the house when my mother was very ill. She did all the heavy work, for mammy was weak, ye know.’ He tells me this during one of our chats. We’re pals and I’m proud to be so. Possessed by football, at just thirteen, he had ‘not a clue’ how ill ‘mammy’ was. When she died – in the early summer of ’61 – he missed her, ‘Ach, I did surely but it was worse for Eileen and Mae.’ Eileen is the eldest and his senior by nine years, then two years below her is Mae. She is my mother and despite being his big sister, she has always seemed, to all of us, the baby. ‘They kissed her and touched her in the coffin but I couldn’t. I didn’t even cry.’

His father Tommy had little interest in the GAA but his mother was ‘football mad’. He doesn’t believe it’s in the genes, though: ‘All oul’ nonsense that. Ye take football after nobody; you’re either good enough or you’re not.’ So, the All-Ireland-winning Derry minor, and All-Ireland-winning U21, is now a successful county manager, in the final with his footballer son – his All-Ireland-winning Derry minor and Ulster U21-winning son.

On the surface, gruff and closed, he has ‘no truck’ with introspection and is famously a terror with sports journalists across Ireland. But, the more abuse he gives them the more their copy purrs. ‘The High Priest of Irreverence’ is ‘roguish’, ‘charismatic’ and ‘shrewd’. But Christ he can give them a lick – and anyone else should they rouse his ire. He’s not bad tempered by any means, full of fun and craic and chat, but his passion for the game is messianic and there’s no mercy – no mercy – for blasphemers.

‘Youse boys knows nathin’ about futball’, he crowed to three unlucky scribes after his team hammered Down on the way to the Ulster Final, the crucial provincial landmark on their All-Ireland championship charge. Against the conquering Mournemen of ’91, the nearly men of Derry hadn’t a chance. ‘Look at the scoreboard, boys. How could yis get it so wrong? Youse can’t know anything about football, youse can’t.’ I know this – the country knows this – as they report their roasting post-match. Out of the sports pages the following day I can hear his voice rising on the ‘can’t’, his South Derry brogue crackling in fury and triumph.

But seven weeks later I am at his side in Clones after Derry’s Ulster Final win. In fact, I’m round his neck and his shoulder and his back, and we’re up to our ankles in the mud of the pitch. I don’t know how I got to him through the victory-crazed throng but we’re jumping and hugging and shouting, delirious with delight. His sisters and my brothers are scattered all around but I’m off into the field and I reach him, just before the gathering press pack. ‘Coleman’, ‘Eamonn’, ‘Eamonn, how does it feel to be Ulster champions?’

‘Get away to fuck outta that will yis? Sure what do you want to talk to me for?’

And they fold with laughter, not with nervousness or embarrassment but with like, ‘Ah here comes Coleman’s craic’, the elite of Ireland’s sports writers facing this Ballymaguigan bricklayer. They soothe, cajole and coax, ‘Ach Eamonn, now, come on’, and I’m jostled back among the microphones, the jotters and the bustling pens. He’ll give them what they need but first he’ll give them hell.

‘Why do they put up with you?’ I ask as we relive the thunder of Clones. It’s a few weeks after the game in my tiny north Belfast home. We’re watching tapes of the great eighties Liverpool teams and talking about Brian Clough.

‘Must be the nice smile, I have’, turn of the head, flash, grin. He does that, he disarms you, devilment dancing from every pore, his smile is full frontal enamel and his green eyes wrinkle and spark. But on the sideline, he’s a demon, pointing and effing and roaring. He’s in front of the disciplinary committee so often, they tell him, ‘Just take your usual seat.’ But not this year, this year he has the best disciplinary record of any manager in Ireland because this year he has the best team. In the semi-final and five points down against the mighty Dubs, the roar of the Derry crowd lifts him out of his boots.

‘Aw God man, it was tarra’, he had thought, ‘it’d be no good if we didn’t win’.

I’d looked down the seats at my uncle, my mammy, my brothers, my aunt. They’re ashen with fear and I pray to my Granda, dead since the November before, ‘Ah Christ if you’re there, Tommy, do something’. A committed non-believer, in desperation I’m a devotee. Derry get their miracle and my family praise the day.

One month later we’re back in Croke Park for the All-Ireland Final against Cork. This time it’s standing room only and I can see nothing through the heaving mass. On my tiptoes, I twist and stretch, smiling frantically at a harassed steward, ‘Are there free seats around the ground anywhere?’ Fifty All-Ireland Finals he’s marshalled and someone always needs a better seat. ‘See that dark-haired man down there?’ I plead, ‘That’s my uncle Eamonn.’

He finds me a seat – among the Cork fans – and laughs, ‘I hope you’re as happy when you come out.’

I am. For the first time in 106 years Derry are All-Ireland kings and my uncle, my godfather and friend is the man to have them crowned. What a feat, what glory, what pride, I babble when I see him after the game. ‘Bullshit this about managers’, he says, ‘the players is the men.’

The victors stay in Dublin for their gala celebration and we file off into the homeward-headed hordes. Out of the capital into Louth, we’re the heroes along the way; the hunters home from the Hill. Kids fly makeshift Derry flags; we honk and beep horns in reply. On the steps of the convent in Drogheda, nuns wave cushion covers of red and white; across the border into Down and an elderly man flies a Supervalu bag, no doubt trailed from a kitchen drawer – the first red and white banner he could find. We know now that thirty-one counties have been at our backs all the way and as first-time winners of the Sam Maguire, they are letting us have our day.

For Eamonn, the next day’s triumphant return proves to be more precious than the trophy he coveted: ‘To come up through Tyrone with the Sam Maguire, I could’ve driv’ up the street again.’ We wait for hours in Maghera with the tens of thousands of others. Red and white. Then … silver. As the victory bus inches towards us, Sam is the masthead at the front. We see Eamonn on the top deck, turn of the head, flash, grin. Then he’s lost in a tumultuous sea as his boys carry him to the stage on their shoulders through the crowds and the crashing waves of unbridled joy. Not one for public speaking, we can hear little of him above the din except, ‘We needed this All-Ireland more than Cork ’cos they already have six.’ Red, white … silver. It’s all black and white to him.

But the elation soon fades to grey – he misses the training and the boys: ‘You feel there should be more, you should have someone else to play. It’s something you dream about all your life and then when you get it, your dream has gone.’

When the Championship of 1994 arrives, the All-Ireland champions are drawn to face Down. ‘One of the best games of football ever played’, he declares after Derry have lost their crown. For the first time in my life at a football match, I’d sank to my hunkers and cried. ‘You never celebrate enough when you win the way you grieve when you lose’: words of his I’d taken little notice of until that sunny day in May. He is more philosophical, although strangely cowed. ‘We were spent; we’d got what we wanted. Down beat us in a brilliant game. It wasn’t as sore as when we’d lost before for we knew we’d be back again.’

‘I always get the dirty jobs’, the county chairman whined as he sacked him. Just three months after that stunning game and Coleman was out the door. Men who he thought were his brothers-in-arms were still in and he was out. He had learned a bitter lesson. ‘I’d have trusted them with my life.’

The coup was followed by a mutiny when his boys refused to play, wouldn’t pull on the red and white or wear the Oak Leaf on their chests. Rumours spread throughout the country, speculation galore: ‘He must have done something’, ‘Ye know Coleman’, ‘No smoke without fire’.

‘Aye that’s how they wanted it.’ He’s gutted, ‘Saying nothing but letting all be said.’ This is a side I’ve never seen to him – bewildered and betrayed. His squat fingers splay in emphasis, the scar on his lip snarling into his cheek.

‘If they’d sacked me because I’d failed then, I’m a big boy, I could take it. But winning forty games from forty-seven, a National League and the All-Ireland, they couldn’t come out and say that; they left a cloud of suspicion hanging over me.’

He challenged them in the press, to their faces and through the GAA. The National League kicked off and still his boys refused to play. Then he blew the final whistle on it. He knew when he’d been beat. ‘If it was me, I’d go back’, he told them, ‘there’s no one person bigger than Derry.’ The officials won their battle but Derry lost the war, it’s twenty-five years later and they’ve never come close again.

A decade after his sacking and the phone rings on my office desk. My older sister Bernadette asks, ‘Can you come and sit with Eamonn?’

‘There’s not a trace of cancer in your body’, the doctor had insisted but now she’s on the phone telling me the doctor had been wrong.

‘He’s got non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Maria.’

‘Non-what? What’s that? Lymphoma?’

‘Yes.’

My brain scrambles to make sense of it. Non is no, which is a good thing, right? ‘That’s a good thing, right?’

‘It’s not good; it’s cancer. Can you just come down? He wants me to go and tell Mae.’

Bernadette waits at the hospital and is standing stock still by his bedside when I arrive. He is upright in the bed, staring straight ahead. His eyes don’t move towards me and there’s a thickness in the room. I’m reminded of an explosion I got caught in as a schoolgirl; the bomb sucked the air out of the street. That’s what it feels like here and I start to gabble to fill the void.

‘The doctor will be round soon … We have to ask about your bloods … We need to find out who the consultant is … What does he think? What’s the next move?’

He’s had enough and snaps, ‘The only thing we have to ask is am I gonna live or am I gonna die.’ My mobile tolls in the vacuum. I leave the ward to take Bernadette’s call. When I come back, he asks, ‘How’s Mae?’ I nod gently, ‘She’s OK.’ He knows that I am lying and then he starts to cry.

After the initial terror, the family machine flicks to ‘on’, through the chemo and the sickness, the waiting and then the reprieve. He takes a holiday to the US and gets engaged to his partner Colette.

‘Engaged’, I congratulate him, ‘at your age, you fuckin’ eejit?’

‘I’m only fifty-eight. I’m thinking I might adopt a child.’ Turn of the head, not quite a flash but he’s still there with that brilliant grin.

Six months later, he feels lumps in his neck. ‘Stem cell treatment’, urge the doctors.

‘What if it doesn’t work?’ asks Mae but I shush her in irritation. It’s devastating what he’s had to go through but it’s not like he’s going to die.

On a perfect June GAA Sunday, I go to Casement to watch our team. At half time the announcer asks us to pray for ‘a great Derryman and Gael’. He’s in the City Hospital just down the road where I’m heading after the game. I tell his partner, his children and his sisters how they chanted his name around the ground but none of it really matters now, and the following day he dies.

On Tuesday afternoon, as our family cars trail the hearse to South Derry, I notice a long line of cars filling the hard shoulder of the motorway. One by one they fall in behind us, the Oak Leaf county bringing him home. And for the next three days they descend; the mourners seem to pour from the skies. Over the brow of the hill they come, across the fields and down the lane. Minibuses are run from the clubhouse to his simple Loughshore home. The pitch where he was forged is now the car park for his wake. It’s like his hallowed St Trea’s grounds are paying homage to their most glittering prize, not the Sam Maguire but the local boy who brought him home: the man who carved a footnote for them in the history of the sport they were built to serve.

There’s coaches from Cavan and Athlone; they come from Kerry, Cork and Down; there’s Mercs with politicians and bigger Mercs with priests. There’s one man in a wheelchair who has no time for football but for ‘the man who, every Sunday, helped me into my car after Mass’. His club mates and his townland take his memory in their arms and they allow us as a family to feel, already, the legacy of the man. On the morning of the funeral, the club’s youngsters line the lane and the boys of ’93 lift him on their shoulders once again.