Читать книгу The Boys of '93 - Eamonn Coleman - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

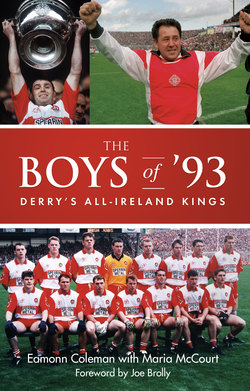

ОглавлениеFOREWORD

by Joe Brolly

When we won the All-Ireland my father painted ‘SAM 1993’ across his oil tank in the yard. Every now and again, he touches it up. When the squad or a few of us meet up, it is always there, unspoken. We don’t talk about the games, or who did what. We talk about the fun and the frolics. And we talk about Eamonn, who was the heart of the group.

‘Wee men can’t drink big pints,’ he roared once at a team meeting, after Johnny McGurk, all 5’ 6” of him, had said there was no harm in a few pints. ‘I could drink big McGilligan under the table,’ said Johnny. ‘Could you fuck,’ said McGilligan. Eamonn burst out laughing with the rest of us, and the temperance lecture broke up in confusion.

For a man who wasn’t academic or well read, he was a superb orator with terrific emotional intelligence. In 1991, we beat Tyrone in a bad-tempered National League final. Seven days later, we met them in the first round of the Ulster championship in Celtic Park. The terraces were bulging. Coleman stood in the middle of the changing room, eyes blazing. Some players he left alone altogether. Others sometimes needed a perk up. ‘Tony Scullion,’ he said, shaking his head in disgust, ‘wait to you hear what Mattie McGleenan said about you in the paper today.’ He opened a newspaper and began to read what the young Tyrone forward had said about Tony. That he was surprised how lacking in pace Scullion was when he marked him in the league final. That he was over-rated. That he was done and that he would make sure he finished him off today. ‘That’s the respect he has for you Scullion, one of the greatest defenders ever to play the game. That’s the respect he has for you,’ he roared, shoving the paper into Scullion’s face. Tony, normally mild-mannered, was enraged. He stood up, roared, and punched the door hard. We rumbled out onto the pitch like marines landing on the beach. Tony was superb in a total shut-out, never giving Mattie a kick.

Afterwards, when we had showered and were leaving, I spotted the paper, scrumpled up under the bench in the corner. I went over and lifted it. I read the interview, smiling and shaking my head. It was nothing only compliments from Mattie. A privilege to play against Tony Scullion and so on. Coleman had made it all up.

He once asked me to come over to the Rossa pitch in Magherafelt the Saturday before a championship match, but told me to say nothing about it. Patsy O’Donnell and Eamonn’s son Gary were there, already togged out. ‘Jody’, he said, ‘I want you to test these two men out.’ I went to full forward. First Patsy picked me up. Half a dozen times the ball was put in for me to run onto, take him on and try to score. Then it was Gary’s turn. Afterwards, Eamonn beckoned me over to the sideline. ‘Well Jody, which one of them would you pick at corner back tomorrow?’ I thought about it for a second, and said, ‘Have we nobody else?’ He tried to keep a straight face, but quickly burst out laughing. ‘What are we going to do with you, Jody?’ he said, as he walked away, ‘what are we going to do with you?’

In 1992, Donegal and ourselves were invited to a civic reception in the Guildhall to celebrate our National League title and their All-Ireland. We were all there, but Donegal sent their sub goalie. Coleman was livid, and viewed it as a deliberate insult. Before we played them in the Ulster Final the following year, he was delivering one of his blistering motivational speeches, not that it was needed. In the middle of it, he roared, ‘That’s how much they think of you. You’re shit under their shoe. They sent the sub goalie to the reception in the Guildhall. Their fucking sub goalie.’ Don Kelly, our sub goalie, put his hand up. ‘What is it, Don?’ ‘I just wanted to say thanks a million, Eamonn.’ The changing room, including Eamonn, exploded into laughter, yet another team meeting ending in confusion.

After we had won the All-Ireland, he invited one of the Biggs brothers into the panel. Gary and Gregory were good dual players and had been making a name for themselves. Biggs arrived for his first session, into this ultra-competitive, seasoned group of All-Ireland winners, led by Henry Downey, who would have intimidated Roy Keane. After the warm-up, we did ten 100m sprints. Then, it was into an A v B game. There was no sign of Biggs. Colm O’Kane, the groundsman, said, ‘He went home after the sprints.’ Coleman called Tohill over and said, ‘Anthony, I think I brought the wrong wan.’

It is no exaggeration to say we loved the man. Maria McCourt’s beautiful book captures a beautiful spirit, and for that we thank her.