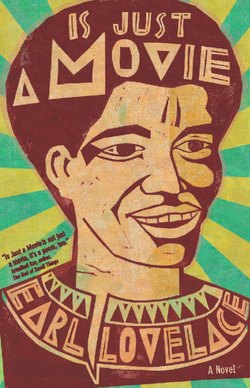

Читать книгу Is Just a Movie - Earl Lovelace - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеRouff Street

Before he came to stay by his grandmother in Cascadu, Sonnyboy lived with his mother at Rouff Street in Port of Spain, up the hill, behind the bridge, between the sounds of the goatskin drums from the Shango Yard by Ma

Trotman, the shouts and pleas breathed from Mother Olga’s Shouters church, the staccato of cussing, the grumble of anger, and the screams of grief that would lodge in his brain and give him his ear for rhythm, so that later, when he started to beat iron in the steelband, what he produced was not the insistent percussive sound to keep the band on the beat, but the discordant chiming clanging clataclanging that opened up the belly of the music to make woman start to wine, young fellars square off to fight and big men put their two hands on their head and weep.

Childhood polio had made one of his legs shorter

than the other, and had given him a slight hop-and-drop walk that was in tune with the music in his belly; and he balanced himself with the awkward elegance of a king sailor on the unsteady deck of the world, out of time with its rhythm, wondering, as he walked through Rouff Street, what disaster had brought him to this place where his ears always ringing, his head always hot, his mind thinking to

get a penknife to cut, a stone to pelt, a bottle to break, trying to understand how he was to be Christian and human in

this mess.

At Escallier RC, where he went to elementary school, his surliness brought him to the attention of the headmaster Mr. Mitchell, who called his mother in to complain about his inattention, the hostility inside him that set him fighting, that make him one afternoon take up the school bell while classes going on and start to ring it, balang! balang! like he summoning a set of dangerous and rebellious spirits. After Mr. Mitchell call her in for the third time, she put Sonnyboy to sit down and explained to him what Mr. Mitchell in his way had tried to tell him but didn’t have the language to get across:

“They put you here in this boiling heat to live, not because this is some wonderful cleansing fire out of which they expect you to emerge productive and restrained. They put you here to kill you. For you to dead. To give you so much pressure that you will turn their brutality against your own brother so that their prophecies would be fulfilled. And the reason why you must listen to what Mr. Mitchell tell you is not because your obedience will bring down blessings from The Most High, either in this life or in the one to come. And not because the mighty will unleash their harshest punishment on you if you break their commandments. They doing that already, and you have done them no wrong. The reason you must stay Christian and human in this place is because, for all the sermons they fling in your direction and the tears they shed in your name, they so expect you to fail, they have a cell and a number waiting for you in the prison and a place to bury you when you dead. Yes, they counting on you to turn up in their jail and on their gallows. Your mission, if you decide to take it, is to disappoint them. Let them claim their victory somewhere else. Leave them with their money and their baubles and their Babel. Leave them with what they have. Don’t give them the pleasure of seeing you inhabit their prison or their hospital or their grave. Do not let them see you vagrant in the road begging them for the crumbs of their pennies. Stay up, so you could watch the surprise in their eyes when they see you still here, when they see they ain’t kill you, when they see that you not dead. Let them marvel, ‘I wonder how this one escape?’ The world is a more than beautiful place. It doesn’t belong to them more than it belongs to you. Yes, to you. Wickedness can flourish, it cannot reign. Things can change. And if all you have to fight with is yourself, don’t do their work for them. Stay strong. Don’t drag down yourself with foolishness.”

She put her arms around Sonnyboy and hugged him to her bosom and he put his arms around her neck and he stay there, hearing her heart beat, feeling her body heave, tasting the tears dripping down from her eyes onto his face before she break away, blinking and laughing: “Go and eat your food. Hold up your head. Look at me. Look!”

Sonnyboy had looked at her live these lessons, herself scrubbing and washing and wrestling the two rooms they lived in into a home, with red lavender in buckets of water, with gully root and sweet broom and blue soap, the four corners of the house smoked with incense, the floors brightened with linoleum, the windows with curtains, the furniture with varnish and the walls with paint, the troughs of earth in the little space in front the house planted with aloes and ginger lilies and wonder of the world, with marigold and zinnias and croton and Jacob’s coat, the plants at her front door flowering with a joy as fertile as the faith she expressed in her singing and her contagious laughter: the scandal of her jokes doubling over the women fetching water or washing or bathing at the single standpipe on the street, lifting them in these magical moments above the mud and the rubbish gathered in the drains, to a height from which to look squarely at the world that looked down on them, the women holding their bellies with two hands to keep from bursting with the sweetness of the pain of the dotishness that flowed from human beings, all of them joined now to a sense of community. Among them the wonderful simplicity of human exchange, plants for their front gardens, remedies for illnesses, consolation for the mother of the girl who get catch with a belly, compassion for the mother of the boy gone off to jail, the exchange and generosity: a dress, a pair of shoes, exchanged, one keeping the children for her neighbor so she could go and release the pressure, dancing to the music of Fitz Vaughn or Sel Duncan; his mother waiting her turn, returning fortified from the standpipe by which she had to bathe, with a bucket of water, her petticoat dripping, the form of her body outlined underneath it, without apology to anyone except perhaps Sonnyboy’s father, the man she had enlisted to help her save herself and him. From her own strength, doing her all to prevent the place from weighing him down, seeing that his shirt was ironed without a crease, that his food was secure, protected from flies underneath the wire netting of the safe, giving him the last of the cocoa or coffee and she and the children drinking teas from shrubs in the yard, vervine, carpenter grass, and Sonnyboy’s favorite, fever grass, consoling him when the fella he was working with as a mattress maker and upholsterer of chairs wouldn’t pay him the money he work for, agreeing with him that “Lance, man, you not cut out for this shit. You have too much talent. You too good-looking to take this set of pressure. And, boy, you have a good voice, you could sing.”

She watched other women watching him when they went to a dance, her mother babysitting the children. He and she in the same color and styled shirt and pants, dancing, her two hands round his neck and the comfort of her bosom against his chest. She watched him move among people with his movie-star smile and relaxed stance, confirming her thinking that no, this cell and prison of Rouff Street is no place for you, expecting him to take off and go away and get out of this place and praying for him to stay, no family to help them, the four brothers of his, each with his own battle to fight, the one older than him who fancied himself a singer, setting out every morning, decked in his white ruffle-fronted shirt with the puff sleeves red, his guitar round his neck, to the Botanic Gardens or the Lady Young Lookout to find tourists to sing them verses of popular calypso or made-up ones of his own on the beauty of the tourist woman, the cleverness of her husband, the loveliness of the island. After they give him some change, going back in time to clip tickets for the 12:30 show at the Pyramid cinema where he held down a job as a checker; another brother, George, the saga-boy, dapper, pants seam cutting, shirt collar upturned, gold chain on his neck, gold teeth in his mouth, every time you see him is with a new woman holding on to him as if she fraid he will fly away if she let go; Calvin, the sportsman, good at cricket and football, going every day to the savannah to play one of the games, sometimes with a bat in his hands, always his wrists bandaged, a knee band or ankle band on, walking with a limp to draw attention to his dedication to sports as well as to his heroic survival; Bruce who coulda been a heavyweight boxer find himself in prison for beating, one by one, seven fellars who sampat him after a dance; and Lance, he, Lance, the one with such good looks and talent and all the promise, stay anchored here making mattresses and upholstering chairs, not, as she thought at first, because of her and the children. Because of a steelpan.