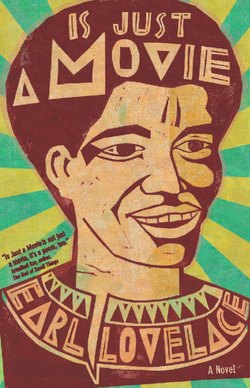

Читать книгу Is Just a Movie - Earl Lovelace - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеRemember the Singing

Rooplal and the Cascadu Years

In Cascadu, Sonnyboy would get a work first on the Carabon cocoa estate, where he would do some cutlassing and weeding, addressing his tasks with a sullen labored care, slower than nearly every other worker, but twice as neat, the grass he cut piled in different-sized artistically shaped heaps, the hedges trimmed neat, the tools washed clean after use, his mouth pushed out, his face severe, his manner abrupt, as if he needed a mask of grumpiness to compensate for the extraordinary diligence of his work. He would carry his slow spiteful thoroughness to the variety of odd jobs that fell to him thereafter, as a yard boy at Choy’s grocery, as a helper at Tarzan’s tire shop, as a laborer at the building sites, where he mixed cement and sand under the impatient supervision of his uncle McBurnie who found his thoroughness commendable Yes, but, Jesus, man, at the rate you working you will put me out of business. Sonnyboy happy to leave that job for one in the sawmill where he could take whole day to clean the machinery, tidy up around the building and bag sawdust for sale. Later as he grew in strength and years he would take his ceremonial thoroughness to the grappling of logs, and canting them, mora, crappo and tapana, onto the platform to be cut into boards or scantlings, as dictated by the owner. On a Saturday afternoon he would head for the river that flowed through a lullaby of bamboos, where with the same labored care he would wash the sawdust out his hair, excavate the sawdust out the cup of his ears and from underneath his fingernails, and fresh and clean set out for the Junction with the tiptoeing walk of a king sailor, muscles rippling, his chest outlined in the new jersey he had bought from what remained after he give his grandmother money from his pay, arriving at the corner to stand and watch cars pass and to smoke a cigarette and drink a beer with Gilda and Terry and Dog, and if he still had money left, cross the road and join the fellars gambling under the Health Office building. And when – not if – he lost, return to the consolation of the Junction to listen to Dog talk about the exploits of badjohns from the city, Gilda tell again the story of To Hell and Back and Shane, Gilda demonstrating the action and whistling the soundtrack to Shane, becoming Audie Murphy crawling on his belly through a hail of bullets, or Jack Palance, with the smooth stutter of a footballer taking a penalty kick, getting off his horse in Shane. He would draw closer to the circle of fellars listening to hear Terry, with subdued laughter, his hand over his mouth at the choicest parts, tell of his adventures with the women he had encountered in the hot dimly lit gateways of the city, detailing the time he and Ralphie meet this woman in a gateway and after haggling with her over the price of her company, following her on tiptoe up some rotting stairs into a dingy room on George Street where, with a lighted cigarette burning in her mouth, she lifted her dress and perched herself open-legged on a stool, blowing out smoke leisurely from the cigarette between her lips while Ralphie did his furious business between her thighs. When it was Terry’s turn and she saw the equipment he was toting, her eyes opened wide and her voice rose in rebuke, “Where you going with that?” And, in a sterner voice, “You not putting that here, you know,” closing her legs, getting off the stool, fixing her dress, I better get out of here, clattering down the steps, grumbling with an intimidating fierceness about their inconsiderateness, their money tucked away in her brassiere.

With nothing sensational to contribute to the evening’s entertainment – he did not have the gift of retelling movies, and the intimate experience he had with women was almost nil and so not something he wanted to reveal – Sonnyboy found himself telling of the first time his father went on the road with the steelpan he had tuned and was attacked by the police, of his own astonishment and outrage as he watched the people unable or unwilling or afraid to retaliate, establishing that episode as the basis of his own resolve, I not fucking taking that, a declaration that even the fellars recognized as his way of sharpening his determination to stand against humiliation from any agency, be it individual or the state. They didn’t burst out laughing like at Terry’s salacious tales or feel the need to draw imaginary guns from their hips as at the adventures of Shane. They listened somewhat uneasily, sensing that Sonnyboy was waiting for the occasion to prove how ready he was to confront the world and they took note to make sure not to be the ones to give him the provocation they believed he was seeking.

And he went on growing into his manness, nurturing his resentment at the world, waiting for it to provoke him, ironing and seaming his trousers and stepping out with what would become his trademark neatness, his long sleeves folded at the cuffs, his handkerchief flapping over his back pocket, his hair in a muff, a little face-powder to take the shine off his forehead, making his way to the fêtes in the RC school, daring the girls to refuse to dance with him, waiting for a fella to oppose him and so provide the confrontation he was inviting. But he was lucky, and the only trouble he get in was a few skirmishes with fellars over gambling and a few over girls at a dance, nothing major, until the stupidest thing get him the trouble his grandmother tell him he was all the time looking for.

One night he and some fellars see this drunk Indian man by the shop, one of them search his pocket and they shared the few dollars found on him. Robbery with violence was the charge. His grandmother couldn’t save him. That was the first time he went to jail, to the prison for youths where he would learn to box, would discover his aptitude for drums and his ability to wring a thrilling delighting power from his favorite percussive instrument, the iron. When he got out two years later, he had this nervousness about him as if he was spoiling for a fight, with a kind of aggressive listening and an ear tuned to pick up any slight, and it would be that keenness of hearing that would get him in the next set of trouble. Some obscenity about his mother. In this one, Marvel had a bottle and he had a knife. Marvel get cut. When he come out of jail, he had added a greater deliberation to his movements and stillness to his stance. He became a fella who although he did not appear to be looking, took note of everything around him. Later, this alertness would grow to become the foundation of a new sense of ease that helped him to control his aggression and banished his nervousness when he began to speak. For this development he had to thank Victor Rooplal, a dougla fella, who the first day he appeared in Cascadu, approached the Junction with a sense of ease, his two empty hands swinging, the pale flabby muscles of his arms displayed in a sleeveless merino, with a tailor’s measuring tape hanging around his neck, and beside him, but not looking at him or speaking, as if they were having a disagreement that they had not resolved, a good-looking, brown-skinned woman, a Spanish, with long black hair, Marissa, a thin noisy battleax of a woman, who could have been at least ten years older than him, carrying in one hand a paper bag with what the town of Cascadu would discover later contained the few clothes she had hurriedly grabbed when she made up her mind to run away with him before the man she was living with came home from work and in the other hand a cage with a young parrot that Rooplal had won some days before in a dice game from a woodsman in Navet, Sonnyboy and the fellars looking out from under the Health Office building where they were playing the gambling game wappie, uncertain of any connection between him and the woman until she stopped, reached into her bosom, took some money out of her brassiere and give it to him without a word and continued walking toward the gas station where it was discovered later a relative lived, while Rooplal crossed the road to the Health Office building, in his hand five single-dollar bills smoothed out and packed together to make them look like a million, fellars seeing him coming, thinking he’s easy pickings made a place for him. He find a place to sit down and begin to call his bets with the careless confidence of a man who know what he doing, and by the time the sun went down that evening he had everybody money in his pocket. Next weekend he would do it again, win-out everybody, leaving fellars to wonder if he was all that lucky or if he had a system of marking cards that nobody could detect. So that after that Saturday the only ones to bet against him were strangers and thirsty, impatient young fellars like Sonnyboy, who initially refused to be intimidated by his apparent skills, but who would in time discover that betting against him was throwing away money.

Rooplal settled down in Cascadu in a little house not far from the RC school, making a living gambling and ministering to distressed women needing help in matters of love, the steady stream of them going to him for bush baths and love potions, women talking of him in whispers, his notoriety spreading among them as an obeah-man, a seducer, whose magical charms none of their gender could resist, and the young fellars of the town holding him up as their authority on women, politics, gambling and race.

Rooplal was of mixed blood, African and Indian, this happy convenience making him welcome in each camp, entitling him to shower abuse on members of either group with a coarseness they tolerated from no one else, no side able to accuse him of prejudice since he shared his heritage with both; in his case, the two bloods canceling out each other, as equally potent warring and destructive poisons whose only virtue was to produce an offspring that was acceptable to both and that could be claimed by neither. Under his influence, Sonnyboy told the story again of the incident with his father, but where in earlier recounting he shared the blame between the people and the police, under Rooplal’s prompting, he now put the responsibility almost solely on the people. Rooplal, it turned out, was also a tailor of some reputation, but had to leave his sewing machine behind because of the circumstances in which he ran away from Navet. By judicious management of his funds, Marissa saw that he paid down on a new sewing machine and did her best to encourage him to give up obeah and gambling.

He worked at tailoring for a little while, but he couldn’t sit still for long in what was his tailor shop while card was playing out in the town, and eventually he spent most of his time gambling and the rest of it dodging men who came looking for him to get the clothes they had paid him to sew. Marissa, who had to bear the brunt of their anger because she was the one they met when they went to his home, now began to appear at the gambling place to call him, with some sternness, to come and complete the work he had accepted down-payment on. She was also not happy with his relationships with the women. She herself had gone to him for help to get her husband to pay her more attention and had ended up leaving the man and running away with him. The less Rooplal listened to her, the more she nagged. She began to reprimand him in public and to do everything in her power to shame him into becoming the man she wanted him to be. They were well matched in the department of stubbornness, he with the ability to ignore her and she with the tremendous power to nag again. She would leave him eventually after years of pulling and tugging, the final straw discovering he and a woman, both of them naked, in a secluded area on the bank of the river, in what he insisted was part of a ritual of healing. That night during an argument with him she burnt herself attempting to lift a pot of boiling water off the fire to pour on him. After that, he became very uneasy in her presence, and their relation went further downhill. One day after another quarrel, while he was under the Health Office gambling, she gathered up her belongings and put them in a paper bag to publicly display how little she had profited from being with him, next, she poured kerosene over all the clothes he had in the house, piled them in the middle of a room and left a lighted candle in the midst of the pile so that by the time it burnt itself out and caught the clothes on fire she would be far away. In a rush of spite she opened the cage and let out the parrot that Rooplal had come to treasure since he had fed it hot peppers to make its tongue flexible and had taught it to use obscene language, but the bird flew around the house for a while and then returned and stood on top the cage. In the end she put it back into the cage and took it with her to the taxi-stand where she stood waiting for a taxi and relating to anyone willing to hear all the intimate business that went on between Rooplal and her, while the parrot who answered to the name Cocotte went on cursing in its cracked voice the private parts of everybody’s mother, until a policeman came. He couldn’t do nothing because the woman was not cursing and there was no law under which he could arrest a parrot. And she went on telling to the crowd that had gathered the terms of endearment Rooplal had used to woo her, the darlings, the sugarplum, the ointments with which he would anoint his body, the places on her own that he would kiss, what he would do with his tongue, where on the bed he would place her, her helplessness in the situation because of the powers to charm that he possessed. She was still carrying on when her taxi came. She had just put one foot in the taxi when the onlookers were attracted to the appearance of a stream of white smoke in the air, somewhere in the vicinity of the RC school. Thinking that it might be a fire, people moved toward it to be sure of what was going on. Marissa coolly completed her entry into the vehicle, the driver moving off slowly, to give occupants of the car the opportunity to see if it was indeed a fire and Marissa the occasion to wave cheekily at what was now becoming a blaze, then, speeding away in the direction of Cunaripo.

After Marissa left, many of the women of Cascadu saw Rooplal as a man to avoid and forbade their female relatives to look him in the eye. For protection against the force of his magical charms, they bathed in water perfumed with sweet broom and red lavender and doused themselves in prevention powders they got from another more reliable obeah-man, kept their heads straight so as not to meet his eyes and fingered their rosaries when they saw him passing. But to another set of women, Marissa’s revelations had added to Rooplal’s mystery and appeal and his homelessness now offered an occasion for their solicitude. After she left, there was a steady stream of women of all levels of maturity who came by with rosaries or ohrinis or religious tracts, about them the soft grace of angels of mercy, shyly asking directions to where he might be found. Many of them offered him temporary accommodation, others offered him food, and some brought clothes. He accepted the full package of accommodation, food and clothes from Miss Zeena, a widow, a soft-spoken big-eye Christian woman with long hair and a body not so much weighed down as propelled by the sincere and muscular roll of a formidable bottom. After six days in which no one in the town saw him, he moved out of her place and settled into a two-roomed house behind the gas station.

With Marissa no longer there to harass him, and without the sewing machine to distract him, Rooplal gave up tailoring, but exposed the town to his other skills. He spoke on the political platform of any candidate who came to Cascadu and who would pay him. He made or pretended to make counterfeit money, and endeavored to find every means of making money without the inconvenience of orthodox labor. He linked up with Alligator Teeth, a loudmouthed big-eyed fella, a mouther whose claim to notoriety was his fearsome-looking teeth, loud voice and his boast that he was not too squeamish to scratch out the eyes or bite off the parts of any man who was so foolish as to get into a fight with him. With him, Rooplal roamed the countryside presenting himself as a maker of counterfeit money and trying to sell people the idea that there was treasure buried in their yards. In support of his claim, Rooplal produced two gold coins, which he said had come from a certain piece of land nearby, from treasure buried in the seventeenth century by Blackbeard the pirate. For a small fee, he was prepared to unearth the treasure. Some people chased him out of their yards, but there were the few who believed they were getting a bargain and paid him to dig, which he did, until they turned their back and he and Alligator Teeth disappeared with whatever money they had been given.

By the time Sonnyboy fell in with them, they had pretty much given up those moneymaking schemes and were focused on the more legitimate activities of gambling. Rooplal’s disregard of the consequences of his actions on himself or on others was what principally fascinated Sonnyboy, and as he listened to Rooplal’s stories of his escapades, the cards he marked, the women he fooled,

the people he fleeced, Sonnyboy glimpsed in that approach to life something liberating, and Rooplal, sensing a willing apprentice to his methods, drew Sonnyboy to him.

Soon Sonnyboy became one of the party, going with them to whatever festivity was taking place in the town and its surroundings: to wakes, with two decks of marked cards and two packs of candles to provide light, at village fairs and sports meetings and harvests, with a folding table on which to play Over Under and Lucky Seven, or the Three Card game, with he, Sonnyboy or Alligator Teeth taking the role of the lucky punter, the decoy, pretending to be the one who could spot the Queen. They took their crooked games also to the various venues for horseracing, the savannah in Port of Spain, Santa Rosa in Arima, Skinner Park in the south of the island and at the open-air venues for Kiddies’ Carnival. They went to Tobago only once and were chased away from setting up a game of their own by the Tobago hustlers and they ended up bathing in the sea and eating crab and dumplings from vendors on the beach at Store Bay. And so he had gone on, guided by the philosophy of how to get his own way and what it is he had to do to end up with a dollar in his pocket.

For Carnival, Rooplal and Alligator Teeth continued their hustle in more artistic vein, taking the role of Midnight Robbers, Rooplal adopting the persona of “The Mighty Cangancero” and Alligator Teeth that of “Ottie the Terrible.” They left Cascadu and headed for Port of Spain, stopping at towns along the way, engaging each other in mock confrontation, drawing audiences at every street corner and coming away with purses full of money.

Hear Rooplal, The Mighty Cangancero:

Away from the dark lagoon of gloom came I the Mighty Cangancero, the most notorious criminal grand master.

With my every step, I cause the earth to tremble, my smile brings rain.

My laughter causes the heavens to rumble, trees to fall, rivers to overflow, animals to stampede and human beings to look for shelter.

I am known in Mars, Jupiter, Saturn and the planet they call Uranus,

I am the intergalactic bandit whose face is on the Most Wanted list of bank robbers, kidnappers, plunderers, assassins and bounty hunters.

I traffic in precious metals, rubies, diamonds and pearls.

For I am the most notorious criminal that was placed upon the face of the universe. Everywhere I go the police and secret services of the planets are on the lookout for me.

I am Public Enemy numbers one two and three.

So bow, Mook-man, and deliver your treasures unto me.

And Alligator Teeth, Ottie the Terrible:

Are you not afraid to walk this long lonely road, where I this bloodthirsty terminator performs his daring crimes. For I live today when men who seek to destroy me are all dead. I can bite off a portion of the moon and shorten a season. A breath from my nostrils can melt the north pole, inspire raging torrents, overturn continents and cause islands to disappear. A wave of my hand can stop rain, and cause, in what was once luxurious green, the panic of deserts to appear. Women moan and children groan when meeting me, this criminal master, so for your own good, I ask you to seek my sympathy and bow, Mook-man, and deliver your treasures unto me.

Sonnyboy did not go with them. He headed directly to Port of Spain to link up with his brother Alvin and other relatives who from whichever part of the island they lived would find their way into Tokyo steelband, all of them, the whole Apparicio clan, the older ones holding aloft bits of shrubbery, the younger ones waving handkerchiefs, the streets of the city their own for this one time of the year, so they have no fear of nothing, nobody could touch them in this band, people had to clear the road for them; Sonnyboy himself lined up with the rhythm section, the assembly of hard-muscled men, there to keep up the tempo and maintain the rhythm, as the guardians and force of the band, armed with an instrument that had the heft of a weapon they could employ if the need arose to fight. But fighting was out now; their mission was to give life to music, to make the rhythm sing, to draw people into the Festival of Spirit, into the Orisha of dance, into the defiant consolation of song, so they could know that poverty was not strong enough to overwhelm them, nothing could subdue the freshness of their enduring, nothing overwhelm the monument of their spirit, or overturn the cathedral of their dreams; Uncle George, the smooth one, the saga-boy, older now, with what remained of his hair still black, still slicked back, still neat, with two gaudily dressed and made-up women holding on to him, but not with the desperation of those of an earlier time, more as if supporting him; Sonnyboy’s uncle Egbert, the one who tried to be a calypsonian, his shirt open showing his chest, portraying a wounded soldier, dressed in an army jacket, his head bandaged, embodying the response to the unutterable poignancy of the occasion by drinking to excess and wanting to fight, less to inflict hurt, it turned out, than to engage another human being, to let out this thing he couldn’t express, this love that he was trying to find a way to give, in the end quieting down like a child, collapsing with that rubbery yielding, embracing the very ones a moment before he wanted to fight. Sonnyboy watching the pantomime of grief and nostalgia as Egbert staggered along, his arms thrown over the shoulders of the two men carrying him, not knowing what to do with himself, wanting to challenge the world, to fight with it, wanting it to know that he hurt, that something was missing. Sonnyboy held the tears inside himself, cradling the iron and looking across at another uncle, beating iron beside him, Bruce, a big strong man who Sonnyboy see one time bathing at the standpipe, having soaped his skin, lift a tub of water and pour it over his body to rinse off, Bruce now with the iron up under his chin like is a violin he playing, except that instead of sawing across the instrument, beating down on it, his arms curled and glistening, his shirt front wet with sweat, the music in his head, in his ears, in his belly, in his stones, and Bruce looking across at him too, striking the iron with a fresh resolve to challenge and encourage a new intensity from him to match and counterpoint his beating, Sonnyboy calling upon his muscles for the effort, feeling them respond, the iron ringing afresh, clatack, clatack, clatacanging with a new triumphant benediction. And behind them, in the band, people flowing with their soothing rousing dance, every triumph and disappointment and pain understood, a fella with the mincing, zany elegance of the king sailor, moon-walking across the street, the sweet obscenity punctuating the sober poetry of his uncle Egbert’s challenge to the world: “Beat that! Beat that!” opening his arms and pointing to the pans, to the music, to the dancing: “Beat that!” Beat that! Wanting an enemy to fight, finding a brother to embrace. Because this morning he could fly. No army could defeat him, no force could keep him down: Beat that! And his friends would come and hold him and embrace him and understand his tears and rage and pride: Beat that! And, bearing him up, they would flow forward, linked together with arms on shoulders and hands around waists, and he, Sonnyboy, beating the iron, clakatang clakatang, still beating when somebody put the mouth of a bottle of rum to his lips and he throw back his head and drink two-three gulps, still keeping up the rhythm for the band, and next to him his uncle Bruce, with the iron up under his chin, balang balang balang balang bang, everything else forgotten. And that would be Carnival for Sonnyboy.

And he would go back to Cascadu refreshed, renewed, to the sawmill and to the outings with Rooplal and Alligator Teeth, the dance of his king sailor walk giving him a certain unbalance that brought mystery and authority to his bearing, so that Rooplal, ever on the lookout for new moneymaking schemes, seeing him walking said, “Wait. I have the exact job for you. We could start a church. We could make bags of money with you as a pastor.”

“And you collecting the tithes?” he said, turning it into a joke. But it was true. Rooplal was his friend, but Rooplal had not seen him either. Fearful that if he was not careful he would fade into the nothingness of the town, roused from slumber by his one day of Carnival, Sonnyboy grew quiet. He began to cultivate a way of speaking that muffled his words so you not sure exactly of what he saying. He developed a gruffness of manner as the best face with which to face this world, his arms folded across his chest like a genie, his voice clear and decisive when he had to speak, in his eyes a look of inquiry, to keep people on edge, deliberately stepping into their space to unsettle them, to have them shifting and uncomfortable. There were young fellars who were ready to fight him just for that challenge, but his own readiness to oblige them gave them pause. Fellars had to take their time with him. Conscious of his power, he stepped off even slower now, his elbows turned outward away from his body, one foot rising and falling in sync with the other in the rolling motion as if he was pedaling a bicycle, so that even his grandmother find that for a big man he was walking too pretty. And he only begin to think of his future when, participating in one of Rooplal’s audacious schemes that had to do with counterfeiting money, he found himself with Rooplal and Teeth in a room of a house somewhere in the countryside, in the middle of nowhere, while Khalid, the man who had brought them there, lay sleeping. Earlier that evening Sonnyboy had watched him sharpen his cutlass, then release his five pit bulls to patrol his yard. He had then invited them to dine with his family of a wife and five daughters. It was a delicious dinner of curry duck and steamed breadfruit. Khalid had paid Rooplal to produce 1,000 dollars of counterfeit money. Rooplal take the man money and had not delivered. He had danced the man until the man catch up with him. Now he had to produce the money by morning. There was no way that could be done since the whole thing was a con job gone bad. At the dinner Rooplal reminding him again that while he was overwhelmed by his courtesy he did not believe it was really necessary for them to remain. Khalid had in his possession the device to produce the money. All he would have to do would be to open it after the 12 hours. Yes, the man tell Rooplal. But I don’t want to make no mistake. I would rather you remain. And he showed them to the room in which they were to sleep. As soon they enter the room the man give them to sleep in, Teeth start to tremble and then he came up with the idea that they should join hands and pray.

Sonnyboy had actually begun to pray when Rooplal let go of his hand, put a finger over his lips and stepped lightly out the room. He was following the trail of the aroma of desire left by one of the daughters who as they were having dinner had made the fatal error of looking into his eyes and had fallen under his magical spell. He found her in her room quite awake, fully dressed and with a suitcase packed, waiting to be rescued from the boredom of her village and taken to the places of excitement she had seen in his eyes. She was prepared to lead him past the dogs on condition he take her with him. He agreed, and while the rest of the house was asleep, she led Rooplal and his party out of the yard, into the road and to freedom. Rooplal tried to explain to her that life with him would most likely be hard and that he couldn’t immediately provide anything comparable to what she was leaving. She didn’t want to hear anything. She put one arm around his neck and clung to him. She would go wherever he was going. As soon as they walked out of the yard, Alligator Teeth started to run. Sonnyboy followed him. At some distance from Khalid’s house they stopped until Rooplal came with the girl clinging to him and joined them and they set out walking in the direction of Cascadu, until a truck taking produce to the Port of Spain market stopped for them. Rooplal, the girl and Teeth proceeded to ride the truck all the way to Port of Spain, but Sonnyboy got off at Cascadu. He had decided to leave the association with Rooplal and Teeth for good. It was only after the truck had gone that he pushed his hand in his pocket and realized that Rooplal had not given him his portion of the money. Next day, knowing that Khalid and his men would be looking for him, he headed for Port of Spain to cool out by his brother at Rouff Street.

A few weeks later he would hear that Teeth playing badjohn at an excursion in Mayaro had his left hand chopped off just below the elbow by a young fella from Tunupuna whose name he didn’t know was Blade. Rooplal, he would hear, had migrated with the girl to Canada. Sonnyboy would begin a new life as well.

In Port of Spain, Sonnyboy met Big Ancil, who

was originally from Cascadu but now was a supervisor

on a project in Port of Spain. From Big Ancil he got a job as a laborer on the project and he went about his work with few words and his trademark diligence. Struck by his strict mumbling tone and his diligent, if sullen, performance as a worker, Ancil had made him a foreman. He had managed the men under his control with a stern and intimidatory appearance and a minimum of words, spoken in the same mumbling indecipherable language, a display that so impressed Big Ancil (who was also a moneylender) that he employed him to extract money owed him

from delinquent debtors. Later, delighted by his success in this very important matter, Big Ancil, who at that time was supporting the National Party, engaged him to provide protection for their supporters at their meetings

in opposition territory. There he ran in once more to

Big Head and Marvel, who were doing the same pro-

tective work for the Democratic Party. They had allowed their diligence to get out of hand and at their meetings actually began to jostle people who too vocally opposed the party they supported. Sonnyboy was clear. He

didn’t want any war with them. “Live and let live,” he tell them. “All of us getting a bread from the politics. We not here to kill nobody.” And he exacted a truce from them.

One day Sonnyboy was riding in the car with Big Ancil when Big Ancil, who was announcing the details of a political meeting, seized by a fit of coughing, handed the microphone to him. After the shock of discovering how odd his voice sounded, Sonnyboy went on, with the approval and encouragement of Big Ancil, announcing

for the rest of the evening. After that, whenever Big Ancil was tired he handed the microphone to him. At first Sonnyboy gave the information of the meeting, the time, the speakers, the venue; but, bored with repeating the same things again and again, he began to talk about things that interested him, about labor, about workers doing a fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay, about the pressure placed on people who he called the underdog in society, about how it was only one set of people the police arrested. He spoke about the difficulties his mother had to mind him and his brother and of her having to go away to get a better life. He told again of what happened with his father the day he put the notes on the steelpan and how Blackpeople didn’t raise a hand in his protection. All that, Big Ancil came on to say, was what the National Party was going to change. The reason they were voting was to get that better life here. So between he and Big Ancil there developed a dialogue in which Sonnyboy outlined the problems and Big Ancil came on to say what the National Party was going to do about them. Big Ancil was finding driving the van too exhausting and he encouraged Sonnyboy to get his driving permit so he could take over the driving. It was while on his way to have his birth certificate reissued to him at the Red House that Sonnyboy, walking through Woodford Square, came upon the arguments and discussions on religion and politics and race relations that men were having in little groups all over the Square.

With the experience of speaking on the microphone announcing meetings behind him, and with the freedom to speak with authority that he had developed in his association with Rooplal over the years, Sonnyboy entered the discussions confidently. He discovered that there were people saying the same thing he had been saying for years: I not fucking taking that. And he marveled that they didn’t have to tiptoe around the issues. They spoke out bold: I not accepting the world as you have laid it out. These fellars had better words and more history, but the sentiment was the same.

And he told again the story of his father and the inaction of the people and set off a big argument in the Square about whether Blackpeople were to be blamed for their own bad situation. There were those who agreed with him, but others were astonished at his ignorance of a history that had also made Blackpeople their own worst enemy. Blackpeople needed to see the world through eyes of their own.

After that day, Sonnyboy returned to the conversations in the Square, and over the months he began to see the world through eyes of his own and to join in the idea that they had to take power to take back themselves from that terrible history. He was there to see the numbers grow at the meetings and the Black Power movement begin. Sonnyboy joined the Black Power marches to Woodbrook, St. James, Diego Martin, there in the Carnival of claiming. Space and self and voice, history beginning to belong to him. Sonnyboy felt himself coming alive, felt that his arms were now more his own, that there were things to be done. He explained to Big Ancil that he had to say goodbye to the announcing, he had to move on. And since in his own mind he was a soldier, he began thinking of the struggle as something that would pit muscle against muscle. He convinced the Black Power people of his ability as a fighter. They appointed him bodyguard of one of the leaders. They equipped him with a pair of binoculars for him to bring faraway objects near, and he walked around with his king sailor walk, his arms folded across his chest, and a face more serious than anybody’s own, one of the most conspicuous fellars there. But, he didn’t care; he was part of an invincible army, part of the making of a new history. He watched the police vans trailing behind them as they marched to San Juan, Maraval, Cascadu, Couva. He watched the soldiers nodding their heads at the thunder of the speeches. And he with his arms folded, or with the binoculars glued to his eyes as he searched the crowd, for what, he wasn’t clear. And, how quickly things turn around.