Читать книгу Utamaro - Edmond de Goncourt - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Foreword

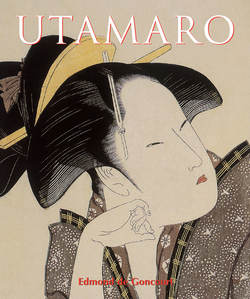

ОглавлениеHanaōgi of the Ōgiya [kamuro: ] Yoshino, Tatsuta (Ōgiya uchi Hanaōgi), 1793–1794.

Ōban, nishiki-e, 36.4 × 24.7 cm.

Musée national des Arts asiatiques – Guimet, Paris.

In his Life of Utamaro, Edmond de Goncourt, in exquisite language and with analytical skill, interpreted the meaning of the form of Japanese art which found its chief expression in the use of the wooden block for colour printing. To glance appreciatively at the work of both artist and author is the motive of this present sketch. The Ukiyo-e* print, despised by the haughty Japanese aristocracy, became the vehicle of art for the common people of Japan, and the names of the artists who aided in its development are familiarly quoted in every studio, whilst the classic painters of Tosa and Kanō are comparatively rarely mentioned. The consensus of opinion in Japan during the lifetime of Utamaro agrees with the verdict of de Goncourt: no artist was more popular than Utamaro. His atelier was besieged by editors giving orders, and in the country his works were eagerly sought after, while those of his famous contemporary, Toyokuni, were but little known. In the Barque of Utamaro, a famous surimono*, the title of which forms a pretty play upon words, maro being the Japanese for “vessel,” the seal of supremacy is set upon the artist. He was essentially the painter of women, and though de Goncourt sets forth his astonishing versatility, he yet entitles his work Utamaro, le Peintre des Maisons vertes.

Dora Amsden