Читать книгу Utamaro - Edmond de Goncourt - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

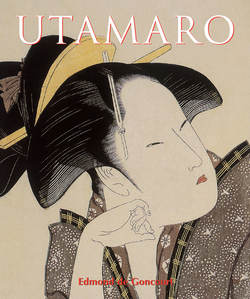

I. The Art of Utamaro

Ukiyo-e, the schools of Kanō and Tosa

ОглавлениеUtamaro has remained one of the most significant artists of the popular Japanese school, so poetically nicknamed “the floating world”: the Ukiyo, from Uki: that which floats above, or overhead; yo: world, life, contemporary time. This term originated during the Edo period (1605–1868) to designate woodblock prints as well as the popular narrative painting (-e: painting). As defined by James Jarvis, the art of Ukiyo-e* was a spiritual approach to reality and the natural conditions of daily life, communication with nature and the spirit of a lively and open-minded people, driven by a passionate appetite for art. The vigour and motivations of the Ukiyo-e* masters and the scope of their accomplishments are proof of it. The true story of Ukiyo-e*, according to Professor Ernest Fenollosa, is not the story of the technique of the block print, even though the block print was one of its most fascinating manifestations, but rather the aesthetic story of a particular form of expression.

The arrival of the popular school of Ukiyo-e* was the culmination of an evolution that had taken place over more than a thousand years, and which, to be understood, requires that we retrace the centuries and review its stages of development. Although the origins of Japanese painting are obscure and clouded by tradition, there is no doubt that China and Korea were the direct sources from which Japan took its art; and yet they were influenced, of course, in less obvious ways by Persia and India, those sacred springs of oriental art and religion, moving forward in concert as they always do. One of the special features of Japanese art is that it was always dominated by the religious hierarchy and by temporal powers. From the very beginning, the school of Tosa owed its prestige to the emperor and his retinue of nobles, just as later, the school of Kanō became the official school of usurping shoguns.

The history of painting in Japan, from the late fifth century until the eighteenth century, can be summed up in the succession of three schools. In the beginning was the Buddhist school, a school brought from the high plateaux of Asia, from wise India, which brought its painting, along with the religion of Shâkyamuni, to China, Japan, and the whole of the Far East. This painting represents the human being in a kind of sacred stasis, avoiding all imitation, refusing to produce portraits, representing the face according to an artistic ritual defined by systematised abbreviations, and concentrating essentially on the details and the richness of clothing.

In China, the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) gave birth to an original style, which dominated the art of Japan for centuries. The ample calligraphy of Hokusai reveals this hereditary influence. His wood engravers, trained to follow the graceful, fluid lines of his work, which was so authentically Japanese, were occasionally disconcerted when he would suddenly veer towards a more angular realism. Two great artistic schools resulted: the school of Tosa and the school of Kanō. The Chinese and Buddhist schools dated back to the sixth century; the emperor of Japan, Heizei, founded the first imperial academy in 808.

“Parody of a Monkey-Trainer” (Mitate saru-mawashi), from the series “Picture Siblings” (E-kyōdai), c. 1795–1796.

Ōban, nishiki-e, 38.3 × 25.1 cm. The Japan Ukiyo-e Museum.

Act Seven from Chūshingura (Chūshingura Shichi-damme), from the series “Chūshingura” (Chūshingura), 1801–1802.

Ōban, nishiki-e, 36.4 × 25.1 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago.

The Chūshingura Drama Parodied by Famous Beauties (Kōmei bijin mitate Chūshingura). Ōban, nishiki-e, 38 × 25.5 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

This academy, along with the school of Yamato-e established by Fujiwara Motomitsu in the eleventh century, led to the renowned school of Tosa which, with that of Kanō, its august and aristocratic rival, kept an uncontested supremacy for centuries, until at last they came to be challenged by the plebeian school of Ukiyo-e*, inspired by the lower classes of Japan.

The school of Tosa was created during the feudal period by a member of the illustrious Fujiwara family, who was vice-governor of the province of Tosa. The school of Tosa represented, in a refined style of aristocratic art, the life of the nobility, both in battle and in amorous and artistic intimacy in the yashiki*, and a revealing specimen of which is the illustration of the love story of The Tale of Genji (Genji Monogatari), written by the woman poet, Murasaki Shikibu. The artists of the school of Tosa used very fine, pointed brushes and brought out the brilliance of their colours against backgrounds resplendent with gold leaf. It is also to this school of intricate designs and microscopic details that we owe those gilded lacquer objects and screens, the richness and beauty of which have never been surpassed.

The school of Tosa has been described as the “manifestation of an ardent faith, through the purity of an ethereal style”, but in fact it was the embodiment of the taste of the Kyōto court and was put at the service of the aristocracy. It was the reflection of the esoteric mystery of Shinto and the sacred entourage of the emperor. The ritual of the court, its celebrations and religious ceremonies, the dances in which the daimyos* took part, dressed in ceremonial costumes falling in heavy, harmonious folds, were depicted with a consummate elegance and a delicacy of touch, betraying in no uncertain terms a familiarity with the arcane methods of the Persian miniature.

The style of the school of Tosa was driven out by the growing Chinese influence, which reached its peak in the fourteenth century, owing to the rival school of Kanō, created by Kanō Masanobu (c. 1434-c. 1530). The origins of this school went back to China. At the end of the fourteenth century, the Chinese Buddhist priest, Josetsu, left his land and set out for Japan, taking with him the Chinese tradition. He founded a new dynasty, the descendants of which still represent the most illustrious tradition in Japanese painting. The school of Kanō constituted a bastion of classicism, which in Japan means, above all, holding to the Chinese models and to a traditional technique, avoiding subjects inspired by daily life. Whereas the school of Kanō absorbed the Chinese influence, the school of Tosa fought against it, thus tending towards an exclusively national art.

Chinese calligraphy is the basis for the technique of the school of Kanō. The Japanese brush stroke follows the Chinese calligraphic tradition, where dexterity, required by these audacious and incisive lines, gives the written sign an effect of drapery or breaks it down into abstract components. The school of Kanō is the school of daring innovation and technical bravura, with the brush pressed wide, with the fineness of a single bristle, with flourishes of the stroke, with the execution which in Japanese is called gaunter, rocky, chopped, rough, with angular contours, sometimes with an excess of the manner, of the “chic” of the Japanese workshop, typical of an aristocratic aesthetic.

“The Fukuju Tea-House” (Fukuju), c. 1794–1795.

Ōban, nishiki-e, 38.2 × 25.3 cm. The British Museum, London.

The Nakadaya Tea-House (Nakadaya), 1794–1795.

Ōban, nishiki-e, 35.8 × 25 cm.

Musée national des Arts asiatiques – Guimet, Paris.

“Reed Blind” (Misu), from the series “Model Young Women Woven in Mist” (Kasumi-ori musume hinagata), c. 1794–1795.

Ōban, nishiki-e, 36.8 × 24 cm.

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Dresden.

“Man and Woman beside a Free-Standing Screen” (Tsuitate no danjo), c. 1797. Ōban, nishiki-e, 37 × 25.9 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The favourite subjects of the painters of the school of Kanō were primarily Chinese philosophers and holy men, and mythological and legendary heroes represented in various attitudes against very conventional backgrounds, made up of clouds and mist, alternating with emblematic elements. Many of the holy men and heroes of the school of Kanō show a striking resemblance to medieval themes, for they are often represented floating above masses of twisted clouds, wrapped in airy drapery, their heads encircled by a halo.

The early Kanō artists had reduced painting to an academic art and had destroyed naturalism until the time when the genius of Kanō Masanobu, who gave his name to the school, and that of his son, Kanō Motonobu (1476–1559), the true “Kanō”, came along to add the warmth of colours and the harmony of composition to the Chinese models and their monochromatic monotony, regenerating and enlivening this style.

During the anarchistic period of the fourteenth century, Japanese art stagnated, but a renewal followed, very similar to the Renaissance in the West. In Japan, as in Europe, the fifteenth century was fundamentally an age of renewal. By the end of that century the principles of Japanese art were permanently fixed, as in Florence where, at almost the same time, Giotto was establishing the canons of art which he had himself inherited from the Greeks of Attica, through Cimabue, and which John Ruskin condensed into a grammar of art, under the title of the Laws of Fésole. It has been said that Japanese art in the nineteenth century was nothing more than a reproduction of the works of the great masters of the past, and that the methods and manners of the artists of the fifteenth century served as examples for generations thereafter. The prestige and influence of the fifteenth century were enhanced by Tosa Mitsunobu (1434–1525) and by the two great artists of the school of Kanō, Kanō Masanobu and Kanō Motonobu, of whom it was said that he “could fill the air with beams of light.”

The two major schools, Tosa and Kanō, evolved separately until the middle of the eighteenth century, when the genius of the popular artists, coming together as the Ukiyo-e* school, brought about the progressive merger of their traditions, absorbing the methods of the two rival schools, which, although divergent in their techniques and motivations, were united by their haughty disdain for this new art, which dared to represent the manners and customs of the common folk. Suzuki Harunobu (1724–1770) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), Torii Kiyonaga (1752–1815) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) were the shining lights of these schools, artists whose genius narrated the story of their country, day by day, weaving a century of history into a living encyclopaedia, sumptuous in its form, kaleidoscopic in its colours.

The Ukiyo-e* bridged the gap and became the representative of both schools, causing an expansion in this art which would never have happened under its aristocratic rivals. Japanese art seems always to have been subject to these kinds of reciprocal influences. The school of Tosa, famous for its delicacy, the minutiae of its details and the brilliance of its colours, succumbed to the dynamic power of black and white from the school of Kanō. The latter, in turn, was modified by the bright colours introduced by Kanō Masanobu (1434–1530) and Kanō Motonobu (1476–1559). Later, the rich palette of Miyagawa Choshun (1683–1753) replaced the monochromatic simplicity of Hishikawa Moronobu (1618–1694), the inspiration for the Ukiyo-e* wood carvers.

The 1790s were a turning point in the development of Ukiyo-e*: from the point of view of technique, the colour block print was perfected, using successive printings onto the same proof using several blocks inked with different colours. These multicoloured xylographs printed on thick paper using the technique of embossing to enliven the white surfaces, are referred to as nishiki-e*. They were the avant-garde of an unconventional art which dealt with the populace and daily life. The realism of the poses, attitudes, and movements thus gave a nearly photographic view of the day-to-day existence of women under the Empire of the Rising Sun. The Ukiyo-e* block print, scorned by the arrogant Japanese aristocracy, became an artistic medium for the common folk of Japan, and the names of its artists were bandied about with familiarity in every atelier, much more so than the names of the classic painters of the schools of Tosa and of Kanō.

The time of Utamaro was the period which saw a great expansion in publishing, through the broadening of the public and diversification in the kinds of works offered. Thus, a market for illustrated books and books for “entertainment” (goraku) grew up, starting from the middle of the eighteenth century in Edo, the place of residence of the Tokugawa shoguns who wielded the actual political power, in Osaka, the great commercial centre for the eastern part of Japan, or in Kyōto, the imperial capital. The publishers of these works, organised into guilds different from those of the publishers of “serious” books, outdid each other in finding ingenious ways to meet the increasing demand from a public eager for illustrated romantic or humorous stories. This public included not only the lowest classes, whose literacy rate was probably high, owing to the “temple schools” (terakoya), but also educated warriors or merchants seeking clever entertainment and more subtle humour, or just beautiful picture books. Booksellers and publishers were always on the lookout for a talented Ukiyo-e* writer or painter who could assure them of a successful publishing run.

The Ukiyo-e* paved the way for the opening of Japan to other nations, by developing among the population an interest in other countries, in foreign knowledge and culture, and by promoting the desire to travel by means of books illustrated with diverse and varied scenes. It was to the Ukiyo-e* that the Japanese owed the progressive germination of an international conscience culminating with the revolution of 1868, which broke out as though miraculously. However, the ferments of this apparently spontaneous arrival of the Meiji era (1868–1912) were spread by the artists of the Ukiyo-e*.

“Miyahito of the Ōgiya, [kamuro: ] Tsubaki, Shirabe” (Ōgiya uchi Miyahito, Tsubaki, Shirabe), c. 1793–1794.

Ōban, nishiki-e with white mica ground, 38.2 × 25.5 cm.

Honolulu Academy of Arts, Honolulu.

“Appearing Again: Naniwaya Okita” (Saishutsu Naniwaya Okita), from the series “Renowned Beauties Likened to the Six Immortal Poets” (Kōmei bijin rokkasen), c. 1796. Ōban, nishiki-e, 38.5 × 26 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Dressing the Hair (Kami-yui), 1794–1795.

Ōban, nishiki-e, 38 × 25.2 cm.

Musée national des Arts asiatiques – Guimet, Paris.