Читать книгу Propaganda - Edward Bernays - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

II.

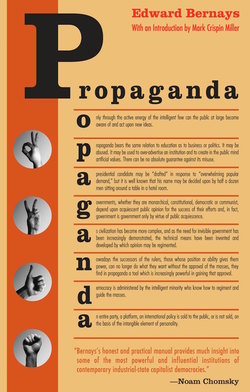

ОглавлениеEdward Bernays’s Propaganda (1928) was the most ambitious of such efforts. Through meticulous descriptions of a broad variety of post-war propaganda drives—all of them ingenious, apparently benign in purpose and honest in their execution—Bernays attempts to rid the word of its bad smell. His motivation would appear to be twofold. Bernays always deemed himself to be both “a truth-seeker and a propagandist for propaganda,” as he put it in another apologia in 1929.7 On the one hand, then, his interest would be purely scientific; and so his effort to redeem the word is based to some extent on intellectual necessity, there being no adequate substitute for propaganda. In this Bernays was right (and never quite gave up his preference for that word over all the euphemisms).8 His wish to reclaim the appropriate term bespeaks a serious commitment to precision; Bernays was not one to hype anything—not his clients’ wares, and not his craft.

In Propaganda, as in all his writings, there is none of the utopian grandiosity that marks so many of the decade’s other pro-commercial homilies. Bernays’s tone is managerial, not millenarian, nor does he promise that his methodology will turn this world into a modern paradise. His vision seems quite modest. The world informed by “public relations” will be but “a smoothly functioning society,” where all of us are guided imperceptibly throughout our lives by a benign elite of rational manipulators.

Bernays derived this vision from the writings of his intellectual hero, Walter Lippmann, whose classic Public Opinion had appeared in 1922. From his observations on the Allied propaganda drives’ immense success (and his own stint as a U.S. war propagandist), and from his readings of Gustave LeBon, Graham Wallas and John Dewey, among others, Lippmann had arrived at the bleak view that “the democratic El Dorado” is impossible in modern mass society, whose members—by and large incapable of lucid thought or clear perception, driven by herd instincts and mere prejudice, and frequently disoriented by external stimuli—were not equipped to make decisions or engage in rational discourse. “Democracy” therefore requires a supra-governmental body of detached professionals to sift the data, think things through, and keep the national enterprise from blowing up or crashing to a halt. Although mankind surely can be taught to think, that educative process will be long and slow. In the meantime, the major issues must be framed, the crucial choices made, by “the responsible administrator.” “It is on the men inside, working under conditions that are sound, that the daily administration of society must rest.”9

While Lippmann’s argument is freighted with complexities and tinged with the melancholy of a disillusioned socialist, Bernays’s adaptation of it is both simple and enthusiastic: “We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.” These “invisible governors” are a heroic elite, who coolly keep it all together, thereby “organizing chaos,” as God did in the Beginning. “It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind, who harness old social forces and contrive new ways to bind and guide the world.” While Lippmann is meticulous—indeed, at times near-Proustian—in demonstrating how and why most people have such trouble thinking straight, Bernays takes all that for granted as “a fact.” It is a sort of managerial aristocracy that quietly determines what we buy and how we vote and what we deem as good or bad. “They govern us,” the author writes, “by their qualities of natural leadership, their ability to supply needed ideas and by their key position in the social structure.”

Although purporting vaguely to be one of “us,” it soon becomes quite clear that Bernays sees himself as an exemplar of that elevated supervisory network, just as he sees his own profession as the most important one up there. Thus Bernays proceeds as both “a truth-seeker and a propagandist for propaganda”; for while he did believe wholeheartedly in his hierarchical conception of “democracy” (and so went on believing through the many further decades of his life, as Stewart Ewen tells us),10 Propaganda is primarily a sales pitch, not an exercise in social theory. In other words, while Propaganda is by no means an exhaustive treatment of its subject, the book is edifying for its own propaganda tactics, and for the light it sheds obliquely on the hidden zeal with which most winning propagandists do their work, however “scientific” and detached they may appear to be (even to themselves).

Apparently a cool defense of propaganda and its salutary influence on mass society, this book is an extended ad for “public relations” as Bernays himself had learned to practice it with rare intelligence and skill. By 1928, he had become the leading figure in his ever-growing field. Not only had he managed to legitimize his craft (“Counsel on Public Relations” always was his pointed self-description), but his own shop was bustling. His services were therefore not available to everyone; Propaganda is aimed mainly at Bernays’s potential corporate clientele. And yet the author variously masks that plutocratic bias. At the outset, his seductive use of “us” implies that he, like most of us, is just a fuddled propaganda, and not himself the ablest of “invisible governors.” In Chapter I, he further mystifies the status of his usual customers by casting “propaganda” as a sort of populist endeavor, and not as an expensive game that is played best by those who have the most to spend on it. Bernays does this by compiling ostentatiously “inclusive” lists of what he represents as common propaganda sources: catalogues, primarily, of modest civic and professional associations and publications (the Arion Singing Society, the National Nut News), with few, if any, blue-chip outfits mentioned. And perhaps Bernays was also disingenuous in filling out the volume with its late, brief chapters on how propaganda can serve education, social service, “art and science”—little forays into social and/or cultural concern, intended, seemingly, to make the book seem something other than an essay on how business stands to benefit immensely from the author’s sort of expertise. All such quasi-democratic touches notwithstanding, Propaganda mainly tells us that Bernays’s true métier was to help giant players with their various sales and image problems.

At that sort of effort he was in a class all by himself; Ivy Lee was the only other P.R. man of comparable renown, and his accomplishments were nowhere near as many or as dazzling as the ones described in Propaganda, not to mention all the others that the author managed after 1928. The book is most instructive when it tells us how and why Bernays did what he did for his (mostly) corporate clients. There are many such revealing moments here—for every case of winning propaganda cited in the book was actually Bernays’s own handiwork. (The casual reader sees no egotism in such self-promotion, as Bernays discreetly slips into the passive voice each time he tells us what “was done” or “shown” or “proven” with extraordinary deftness.) He had no equal as a propaganda strategist. Always thinking far ahead, his aim was not to urge the buyer to demand the product now, but to transform the buyer’s very world, so that the product must appear to be desirable as if without the prod of salesmanship. What is the prevailing custom, and how might that be changed to make this thing or that appear to recommend itself to people? “The modern propagandist … sets to work to create circumstances which will modify that custom.” Bernays sold Mozart pianos, for example, not just by hyping the pianos. Rather, he sought carefully “to develop public acceptance of the idea of a music room in the home”—selling the pianos indirectly, through various suggestive trends and enterprises that make it de rigeur to have the proper space for a piano.

The music room will be accepted because it has been made the thing. And the man or woman who has a music room, or has arranged a corner of the parlor as a musical corner, will naturally think of buying a piano. It will come to him as his own idea.