Читать книгу Soulful Creatures - Edward Bleiberg - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIt was his Majesty that did this in accordance with ancient writings.

Inscription of Amenhotep III {1}

History reveals the ancient Egyptians’ inclination to follow the traditions of their predecessors. Royal inscriptions, such as the one just above, frequently express the pharaohs’ veneration for the past, and their desire to preserve and enhance it. This may be the reason behind the often-noted lack of change in Egyptian civilization for virtually three millennia.

Nonetheless, the Late Period of Egyptian history did witness a significant change—a great surge of animal cults and the mummification of animals. The surge is often explained by scholars as a novel innovation, detached from earlier Egyptian culture or religion. In spite of such assertions, however, animals had remained enduring, essential symbols of nature, the domestic sphere, and the supernatural throughout the long history of Egypt. The Egyptians’ determination to continue and advance the traditions of their predecessors suggests that the sudden rise in popularity of animal cults in the Late Period may in fact have grown out of earlier practices and beliefs concerning the animal world.

With that possibility in mind, let us examine the prevailing views of animals in traditional pharaonic culture in more detail, and see what kinds of longstanding beliefs may have prepared the way for the later rise of animal mummification.

Beliefs about Individual Species

Animals were believed to have been created at the same time as humans. And after their death, animals, like deceased humans, were referred to as “Osiris,” enjoying a semi-divine status.

In the earthly realm, Egyptians saw animals as an integral part of their environment: fish were abundant in the life-giving waters of the Nile; gazelles, lions, and scorpions roamed the desert’s edges; birds of prey flew overhead (figure 12) , and waterfowl chirped in the marshes. Naturally, many animals performed roles familiar to modern Western societies: they were hunted, consumed, bred, or kept as pets. Domesticated goats, sheep, and cattle were used in farming and as a source of food. In addition to providing companionship, cats helped keep vermin away, and dogs assisted in hunting.

The Egyptians keenly observed local creatures in their habitats, and quickly gained an appreciation for the diversity of animals and the specific qualities of each species. Many held a deep significance, being honored for their strength, power, speed, fertility, and other discernible features. Because attributes such as these manifested more strongly in animals than in humanity, they were regarded as evidence of an animal’s link to divinity, possessing qualities of the deity’s character. As a result, some species came to represent specific deities or symbolize particular forces of nature. For example, the aggressive, uncontrollable lioness could embody the violent goddess Sakhmet, and a crocodile could personify the annual inundation. Wild animals that inhabited the threatening desert or the perilous parts of the Nile valley symbolized the dangers associated with these locations (figure 13) . Gazelles and scorpions likely represented the desert. The Nile and its surrounding marshes were characterized by both beneficial and potentially destructive animals like fish, turtles, crocodiles, and hippos. These were seen as symbols of the chaotic abyss known as Nun—the fertile, watery state of the universe before creation.

The profound complexity of animal nature is reflected in Egyptian mythology, supplying many creatures with dual, often opposing, roles that illuminate the sacred and the mundane, the benevolent and the dangerous. Thus, cattle were an everyday source of beef and milk, but a bull with certain markings became a “divinity.” In addition, virtually every animal was recognized to have both benign and malicious aspects. For example, the hippopotamus’s preferred Nile habitat associated it with the life-giving waters of the inundation, yet its aggressiveness when with young epitomized danger and evil. Because of this, the female hippo became a strong symbol of fertility as the goddess Taweret, who protected mothers and newborn babies, while the animal’s hazardous aspect was turned against the dangers of the Netherworld, protecting the reborn deceased in Middle Kingdom tombs (figure 14).

With their varied qualities, some animals represented more than one god. For instance, the falcon symbolized Egyptian kingship, but was also a manifestation of the sun god (figure 15). A falcon’s soaring flight and keen eyesight embodied essential aspects of the god Horus, who often appears as this bird of prey. In another example, the venomous bite of the cobra associated it with the sun god’s arch-enemy, the serpent Apep, and at the same time allowed it to be a powerful protector of the king and the deceased as the uraeus, a form seen on royal headgear (figure 16).

Animal Imagery

As we have seen, commonly encountered animals figured prominently in Egyptian mythology. The image of a cow giving birth to a calf translated into a symbol of fertility, maternal protection, and the daily birth of the sun from the sky goddess.{2} Deities in animal or combined human-animal form proliferated in official Egyptian religion, with their own temples or shrines throughout the country. On a private level, images of animals appeared on objects of worship and amulets. Scribes kept small images of seated baboons, representing their patron god, Thoth, and pregnant mothers used amulets of the hippo Taweret for protection at home (figure 17) .

Representations of domesticated cattle, sheep, and goats emerged around 5000 b.c.e. at sites like Merimde, one of the earliest settlements in the Nile Delta. Depictions of animals as figures and on palettes, ritual combs, and knives were already common in Predynastic times.

Images of Royal Authority

Predynastic images of wild-animal hunts show a desire to capture and control creatures associated with the margins of creation, for use in protective temple rituals. One of the most important Predynastic settlements of Hierakonpolis, dated to Naqada II–III (circa 3500–3100 b.c.e.), revealed a variety of ritually buried animals, including cattle, hippopotami, donkeys, dogs, baboons, gazelles, crocodiles, and elephants, among others.{3} Their healed bone fractures suggest that some wild and rare animals remained in captivity for a certain time before being sacrificed.

In the Predynastic and Early Dynastic Periods, the iconography of royal authority included lions, bulls, and other large, powerful creatures. Like these fierce animals, the early rulers subdued neighboring chiefs and kept them at bay. At the same time, the ability to capture and effectively control large wild animals served as a display of supremacy for Predynastic chiefs. Interestingly, the names of early rulers, like Narmer, whose name means “catfish,” and his likely predecessor Scorpion, refer to dangerous and aggressive, if smaller, animals.

By the time the Egyptian state formed, the significance of certain animals was firmly established in the culture. Under a government that was newly stable and powerful, symbols of overarching control gained special importance. Although rarely depicted in the Predynastic, the falcon appeared at the pinnacle of Early Dynastic iconography, identified as the god Horus, the symbol and protector of Egyptian kingship (figure 18) . And with the development of writing and the standardization of art, the integral place of animals in the Egyptian worldview became more apparent. The Egyptian conception of creation described animals as an equal part of creation, along with humans, as a New Kingdom hymn to the god Aten emphasizes: “August God who fashioned himself, who made every land, created what is in it, all peoples, herds, and flocks, all trees that grow from soil; they live when you dawn for them.”{4} Despite this seeming equality, however, evidence points to captured wild animals kept in a zoo-like enclosure in the New Kingdom palace of Amenhotep III. Similarly, Old Kingdom and later tombs abound in images of domesticated cattle and goats, while scenes of fishing, hunting, and bird netting represent the margins of the surrounding universe in the tombs’ lower registers.

Animals in Ritual

Animal cults focusing on the worship of a singular, “sacred” animal persisted from the First Dynasty into the Roman Period. Each was a distinct, individual beast with special markings, revered as the chosen embodiment of a specific god. After death, such sacred animals were embalmed and buried with great pomp, becoming the earliest precursors of later animal cults. The role of each sacred animal as the earthly manifestation of a god parallels that of the king, who became Horus when crowned. Both kings and sacred animals functioned as intermediaries between humanity and the gods. At death, both were interred in designated necropolises, next to their predecessors.

The sacred Apis bull played a part in rituals of royal renewal from early on. Coinciding with changes to the Apis cult and establishment of the Serapeum (figure 19), the veneration of more than one representative of a species associated with a god appeared in the Eighteenth Dynasty, and intensified by the Twenty-sixth Dynasty (figure 20).

The archaeological context of Predynastic animal images points to early rituals associated with divinities and their use as votives, another practice akin to later animal mummies.{5} By the Late Period, the connection between animals and religious rituals had become more common, as more animals joined the ranks of semi-divine creatures capable of embodying a god. The gradual growth of animal cults does not have much inscriptional or archaeological evidence, likely because their initial surge took place among the popular, rather than official-temple religion. Eventually, this phenomenon picked up royal support in the reigns of Ahmose II, Nectanebo I–II, and Ptolemy I. At the same time, the taxation of cult centers and offices serving animal cults must have financially benefitted the state in a substantial way.{6}

Mummified Animals: A Brief Bestiary

As the popularity of animal cults grew in the Late Period of Egyptian history, more species were mummified, and in greater numbers. To better understand the phenomenon, let us examine some of the specific kinds of animals that were mummified, their roles in everyday life, and their selected religious associations from preceding periods.

In this brief bestiary, mammals are discussed first (agricultural, then domesticated, then wild), followed by birds, reptiles, fish, and finally insects.

Cattle

Domesticated around 5000 b.c.e., cows and bulls were used as a food source and helped work the fields. Possession of large cattle herds indicated the status of their owner. Scenes of cattle-counting and of assisting in the birth of calves frequently appear in Old Kingdom and later tombs. Models of daily life representing cattle stables and slaughterhouses are numerous in the Middle Kingdom. Beef was part of elite menus, and haunches of beef are typically included as funerary offerings.

Bovines were among the first animals to acquire strong associations with specific divinities, and the first large animals to be venerated and mummified after death. One of the most prominent goddesses, Hathor, depicted as a cow or a cow-headed woman, possessed the cow’s motherly qualities as a producer of milk and protector of calves. Regarded as the daughter of Re and one of the goddesses of the Eye of the Sun, Hathor represented the peaceful, protective aspect of female divinities. Such musical instruments as the sistrum are decorated with faces of Hathor because of her associations with music, love, and sexuality. She was one of the few goddesses with temples throughout Egypt. Hathor, whose name means “House of Horus,” was believed to protect and nurse the young Horus. She is the mother of Horus in Pyramid Text 303, paragraph 466: “You are Horus, son of Osiris. You, Unis, are the eldest god, the son of Hathor.”{7} Following Horus’s link with kingship, Hathor was seen as the divine mother of each king, a notion frequently evoked in scenes of the goddess suckling the king. Also known as the “Lady of the West,” she received and protected the setting sun, and by association, the deceased. Other goddesses, including Nut, Isis, and Bat, were also represented as a woman with cow horns and ears (figure 21) .

The bull’s strength and fertility became symbolic of royal power during the early Egyptian state. Images of bulls depict the sun god, primordial time, and creation; the fore part of a bull represents a constellation in Egyptian astronomical maps. Predynastic and Early Dynastic images of charging bulls symbolized the ruler. Later pharaohs wore bull’s tails in association with the might and virility of this animal, and New Kingdom pharaohs adopted the epithet “Mighty Bull.” Nonetheless, records from the First Dynasty king Aha refer to kings spearing bulls as part of a ritual royal hunt. The choicest parts were subsequently offered to a god, and consumed, allowing the king to assimilate the animal’s strength. The bull’s fertility symbolized one of the most important features of the Egyptian landscape: the annual inundation that brought fertile soil to the Nile valley.

Several bulls were considered to be sacred animals as offspring and representatives of a specific god. The most prominent of these was Apis, venerated since the Early Dynastic Period.{8} Each Apis bull was chosen by its markings: “black with a white diamond on the forehead, a likeness of vulture wings on his back, double hairs on its tail and a scarab-shaped mark under its tongue,”{9} according to Herodotus (figure 22). Believed to be the replication and manifestation (ba) of Ptah, Apis had his principal sanctuary at the temple of Ptah in Memphis. Apis’s importance to kingship is reflected in its role in the royal renewal ceremony of the Sed-festival, where it conveyed its power to the king. After death, each Apis was embalmed, mourned, and buried in places like the Serapeum of Saqqara, with equipment similar to elite human burials. As the bull sacred to the west, the location of most cemeteries, deceased Apises became associated with Osiris as the god Osiris-Apis (Oserapis), and held the epithet “ba of Osiris.” As a direct manifestation of a god, the crowned Apis bull was believed to provide oracles during life and after death. Apis’s oracular abilities likely affected the economic development of North Saqqara, which became the focus of numerous animal cults in the Late Period.{10}

Due to the “divine nature of his birth,” the mothers of Apis (figure 23) were deemed manifestations of the goddess Isis and awarded lush burials in the Iseum in North Saqqara, as were Apis calves. A myth from the time of Nectanebo II refers to Thoth as the father of Apis, perhaps explaining why baboons and ibises, closely associated with Thoth, were also buried in the vicinity of the Serapeum.{11}

The sacred bull of Heliopolis known as Mnevis was identified by its completely black color, which alludes to inundation, pre-creation, and rebirth.{12} Linked with the creator god Atum, and regarded as the ba of the sun god, Mnevis was represented with a sun disk and uraeus between its curved horns. According to the Greek historian Plutarch, the Mnevis bull was second to Apis, and also consulted as an oracle. References to Mnevis bulls date back to the Pyramid Texts, and Mnevis burials are known from the Ramesside period. Mnevises were mummified like humans and received analogous offerings. A boundary stela at Amarna states: “Let a cemetery for the Mnevis bull be made in the eastern mountain of Akhetaten that he may be buried in it.”{13} The mothers of Mnevis bulls enjoyed their own cult as the cow goddess Hesat, and their calves were also entombed in Heliopolis.

A later addition to bull cults, attested from Ramesses II’s reign, was the Buchis, sacred to the god Montu in Hermopolis (Armant) and closely linked with Amun and Min (figure 24). Each Buchis was likely a wild bull, distinguished by its white body and black head.{14} The Roman writer Macrobius (circa 400 c.e.) described the belief that the Buchis bull changed color every hour and its hair grew backwards. As it was deemed to be the ba of Re and Osiris, the bull’s name means “Who Makes the Ba Dwell within the Body.” The deceased Buchis was mummified and buried in sandstone sarcophagi in catacombs called Bucheum. Mothers of Buchis were subsequently interred at Baqariyyah, in Armant, in the Late and Greco-Roman periods. Other localities also worshipped sacred bulls that are less well documented.{15}

Ram

Domesticated in the early Predynastic Period, large herds of sheep were kept for agricultural use and as a source of food. Noted for their aggression and virility, ram deities held epithets like “Coupling Ram that Mounts the Beauties” (figure 25). According to Plutarch, certain taboos against sheep products were in place for priests of ram deities: “because they revere the sheep, abstain from using wool as well as its flesh.” Two types of ram occur in Egyptian art. A ram with short, curved horns (Ovis platyura aegyptiaca), appearing in Egypt around the Twelfth Dynasty, came to be one of the manifestations of the principal Egyptian god, Amun (figures 26 , 27 ), and was particularly revered in this form in Nubian temples. The god Khnum, represented as a ram with long, wavy horns (Ovis longipes palaeoaegypticus, now extinct) or a ram-headed human, was worshipped throughout Upper Egypt with prominent cult centers at Esna and Elephantine. Attested from the earliest periods, Khnum was believed to have created humans, animals, and the universe on a potter’s wheel.

The similarly represented god Banebdjedet was venerated as the united ba of Re and Osiris from the Second Dynasty on. The pure-white sacred ram of Mendes resided in the temple and offered daily oracular statements on the functioning of the state. The roots of the similar Egyptian words sr (“ram”) and sr (“to foretell”) likely fostered belief in this ram’s clairvoyance. Another ram deity, Heryshef, who may have originally been a fertility god, was worshipped at Herakleopolis Magna as early as the First Dynasty. Sacred rams were mummified and buried in catacombs at these and other cult centers of the later periods as well.

Dog, Jackal

As in modern society, already in Neolithic times dogs were used as domestic pets, guardians, herders, and police assistants. Several dog breeds could be found in ancient Egypt, the most popular being the greyhound, basenji, and saluki, all well suited to hunting; an Egyptian vessel from about 4500 b.c.e. in the Pushkin Museum, Moscow, shows a hunter with four dogs. Dogs were depicted as pets under their owner’s chair, and some were buried with or next to their owners. Early rulers of Abydos were buried with their dogs, while the Eleventh Dynasty king Wahankh Intef II included names of his dogs on his funerary stela .

From the First Dynasty, Egyptians venerated several jackal deities. The most prominent of these was Anubis, represented as a canine or a canine-headed human (figure 28). Traditionally, the Anubis animal (sab) has been identified as a jackal, but its generally black coloring, symbolic of the afterlife and rebirth, is not typical of jackals and may instead denote a wild dog. The numerous canine mummies of later periods were buried in the Anubieion catacombs, named after Anubis by later authors. According to myth, Anubis was responsible for embalming the god Osiris, and was venerated throughout Egypt as patron of embalmers. His epithets include “Foremost of the Divine Booth” (that is, the embalming tent or burial chamber) and “He Who Is in the Mummy Wrappings.” Because dogs and jackals roamed the desert’s edge, where the dead were generally buried, they were seen as protectors of cemeteries; alternatively, the use of a canine image in funerary contexts may have reflected a desire to prevent wild canines from disturbing corpses, which they likely did. The so-called seal of Anubis, representing a jackal above nine bound captives, was stamped on tomb entrances in the Valley of the Kings, symbolically protecting the tombs and their occupants. As a funerary deity, Anubis assisted Osiris’s judgment by weighing the heart of the deceased, in the Book of the Dead, Spell 125, while the Pyramid Texts refer to him as the judge of the dead.

The god Wepwawet was similarly depicted as a jackal-headed human, or a jackal with a gray or white head (figure 29). Wepwawet’s cult was especially prominent in Abydos, where he was one of the earliest deities worshipped. His epithets include “Lord of Abydos” and “Lord of Necropolis.” Wepwawet was also worshipped in Asyut, known to the ancient Greeks as Lycopolis (“wolf-town”). The meaning of Wepwawet’s name, “Opener of the Ways,” primarily refers to his role as protector and guide of the deceased through the Netherworld. As such, he performed the traditional Opening of the Mouth ceremony, revivifying the deceased. Wepwawet was also venerated as a royal messenger and the deity who facilitated royal conquests of foreign lands, by opening the ways for the king.

Cat, Lion

Domesticated considerably later than dogs, felines are one of the most iconic species in Egyptian culture. Cat mummies are common in later periods (see figure 109), although lion burials are rarely attested. Two types of smaller cats commonly appeared in ancient Egypt: the jungle cat (Felis chaus) and the African wild cat (Felis silvestris libyca). The latter were kept as pets from the Predynastic Period onward. The house cat’s knack for catching mice and snakes in homes or granaries was highly valued, and was translated into mythology. With their ability to see in darkness and fight off dangerous creatures, various cats regularly appear on Middle Kingdom magical knives and figurines. In the Book of the Dead, the sun god takes the form of a tomcat to defeat the serpent Apep. Tomb scenes of hunting and fowling with the participation of smaller cats symbolically refer to such mythological episodes.

The domestic context and motherly qualities of cats closely link them to the goddess Bastet, who was depicted as a cat or a cat-headed woman (figure 30) . Attested since the Second Dynasty, in her early lion-headed form, Bastet was regarded as a protective mother goddess and the daughter of Re. Small cats frequently appear under women’s chairs on reliefs, evoking fertility and sexuality. Cats’ mythological associations (figure 31) likely explain the use of cat fur, feces, and fat in magic and medicine. The cult of Bastet and her center of worship, Bubastis, the origin of numerous later cat mummies, rose in popularity by the Third Intermediate Period. Accordingly, the Twenty-second Dynasty pharaoh Pamiw’s name means “Tomcat.”

Having retreated south around the Predynastic Period, lions were rare in pharaonic times, but they played a tremendous role in Egyptian iconography. As in many cultures, lions became firmly established as symbols of royal authority for their aggressive nature and their power. Rulers organized lion hunts demonstrating their control of the fierce animal. Lion bones found in the First Dynasty tomb of king Aha suggest that captured lions were kept in royal complexes. Lions often represented the horizons, where the sun rises and sets every day, as the desert habitat mythologically links them with the eastern and western margins of the universe. Lion images on funerary furniture illustrate this animal’s link with the cycle of death and rebirth, akin to the sun. The sun god himself appears as a lion with yellow ruff in the Book of the Dead, Spell 62, and the lion god Aker guards the entrance to the Netherworld. The aggressive power of lions was adopted as a symbol of forceful protection.

The lioness’s motherly instinct, manifested in gentle nurturing and fierce protection of her cubs, represented the mystical duality of fury and care. Although male deities assumed lion shape at times, most lion divinities were female (figure 32). Sakhmet, Bastet, Wadjet, Mut, Shesemtet, Pakhet, Tefnut, and others took the form of a lioness or a lion-headed woman. Many of these goddesses were also closely linked with other animals. The leonine goddesses were daughters of Re, and were connected with the myth of the Eye of the Sun; in one version of this myth, Re sends Sakhmet to slaughter humans, but having changed his mind, Re impedes the slaughter and Sakhmet is transformed into a peaceful cat. The dual role of feline goddesses inextricably links cats and lions, as a myth in the temple of Philae states: “She rages like Sakhmet and is peaceful like Bastet.”{16} The powerful protection of leonine goddesses is frequently used in amulets during life and after death.

Antelope

Egyptians attempted to domesticate the antelope (specifically, the gazelle and the oryx) at an early time, when the climate was damper and antelopes roamed the semi-desert regions.{17} The inability to control these relatively small and unaggressive animals may have contributed to the antelope’s eventual negative symbolism in Egyptian mythology. As a result, magical and protective objects depict them among the creatures under the control of Horus, conveying the power over all potential evil to the object’s user (figures 13, 33).

The multifaceted character seen in many other animals extends to antelopes as well. Despite their largely negative symbolism, their natural grace was observed by the Egyptians, and their image was adopted by minor queens and princesses for adornment and symbolic protection in place of the uraeus. A mummified and carefully wrapped gazelle found in a Twenty-second Dynasty royal cache suggests their role as pets. Like cats and monkeys, common images of gazelles under people’s chairs may symbolize regeneration.

The goddess Satet, venerated in the form of an antelope in the city of Elephantine and believed to guard the southern border of Egypt, was depicted as a woman with an antelope-horned crown. Satet’s name means “She Who Shoots/Pours Out,” and her epithet “Mistress of the Water of Life” closely linked her with water. Pyramid Texts describe her as purifying the deceased king. First signs of the inundation were observed annually at Elephantine, the location of Satet’s temple. Also associated with gazelles was Satet’s daughter, the huntress Anuket, whose cult dates back to the Old Kingdom. With her main temple at Elephantine, next to the first Nile cataract, Anuket’s festival commenced the annual inundation.

Monkey, Baboon

Mummies of monkeys appear in almost every animal necropolis of the Ptolemaic Period, but it is unclear whether monkeys were ever native to Egypt. If they were, they must have moved south, along with elephants, lions, and other savanna animals, at the end of the Predynastic Period. Monkeys enjoyed great popularity among the Egyptian elite. Records of Hatshepsut’s expedition to the south{18} and the tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor{19} describe their importation into pharaonic Egypt from Nubia and Punt. Tomb scenes and stelae dating back to the Fourth Dynasty depict monkeys under people’s chairs, suggesting their role as pets. Such images may represent sexuality, as texts indicate monkeys’ significance for rebirth. As such, monkeys were at times buried alongside humans. Although scenes of monkeys and baboons performing agricultural tasks have been interpreted as evidence of their service to humans, this theory remains questionable due to the rarity and presumed cost of these animals in ancient Egypt. Satirical depictions on inscribed potsherds and stone flakes, known as ostraca, and on papyri, particularly from the New Kingdom, include monkeys performing such human tasks as playing musical instruments. In mythology, the green monkey represents aspects of sun and moon deities, and accompanies the sun god in Netherworld books. Strangely, no cult of monkeys existed.

Like monkeys, baboons were not native to Egypt during much of the pharaonic period. Excavations yielded baboon burials at Hierakonpolis already in Naqada III, and Early Dynastic votive figurines of cynocephalus baboons from Abydos (figure 34) . The Egyptians observed baboons getting up on their hind legs and raising their arms every morning to warm their bodies as the sun came up after a cold night. Because the gesture closely resembled that of adoration in Egyptian hieroglyphs, baboons appeared to greet and worship the rising sun each morning, reinforcing their link with the sun and moon.

In the Late, Ptolemaic, and Roman Periods, baboons were equated with Osiris, mummified and carefully buried in catacombs. From the time of Ptolemy I, burials of sacred baboons included personal names of each baboon, genealogies, and dates of birth and death, as well as references to the new god traveling with the sun god in his boat. “Osiris-baboon” (wsir-pa-aan) was venerated alongside “Osiris-ibis” (wsir-pa-hb), another form of Thoth. Thoth, the purveyor of writing, knowledge, and recordkeeping, was frequently portrayed as a cynocephalus baboon. The god Hapy, one of the four sons of Horus connected with mummification, was typically depicted with a baboon head. The squatting baboon god Hedj-wer (“The Great White One”) represented the king himself for the royal ancestors who symbolically confirmed the newly appointed king. This deity occurs in the Early Dynastic Period and the Old Kingdom, but comes to represent Thoth and the moon god Khonsu thereafter (figure 35) . Thoth records the results of Osiris’s judgment of the dead, and baboons appear in the vicinity of scales, weighing the deceased’s heart in the Book of the Dead, Spell 125.

Baboons’ aggressive nature places them as guardians of the Netherworld Lake of Fire, where the sun regenerates daily. The Book of the Dead, Spell 126, describes them as those “who judge between the needy and the rich, who gladden the gods with the scorching breath of their mouths, who give divine offerings to the gods and mortuary offerings to the blessed spirits, who live on truth and sip of truth, who lie not and whose abomination is evil.” Their temperament is reflected in the hieroglyph “to be furious,” representing a baboon with a raised tail. The largely negative divinities like Seth and Apep at times assume baboon forms.

Ichneumon, Shrew

A large type of mongoose common in Africa, the ichneumon (Herpestes ichneumon; figure 36) is represented in Egyptian art from the Old Kingdom onward. Venerated for its ability to kill snakes, the ichneumon was related to Horus and Atum, among others, and worshipped throughout the country (figure 37); in fighting the divine serpent Apep, the sun god is said to have taken the form of an ichneumon with a sun disk surmounting its head. The normally feline goddess Mafdet, venerated for her power over snakes and scorpions, at times assumed the form of a mongoose; Mafdet protected the deceased from snake bites in the Book of the Dead, Spell 149, by beheading venomous snakes in the seventh mound of the Netherworld.

The shrew, a mouse-size nocturnal mammal, substituted for ichneumons in Egyptian myth (figures 38, 39). Believed to have vision in both light and darkness, the god Horus Khenty-irty of Letopolis was represented by the wide-eyed type of ichneumon and the shrew, respectively. Shrews appear as the focus of worship particularly in the Late Period.

Duck, Goose

Indigenous and migratory birds were plentiful in the Nile valley. Waterfowl that appeared in Egypt during the annual migration brought together the elements of water and sky. Several religious texts imply that stars turned into fish in the waters of Nun, and flew up to the sky as birds. Tomb scenes depicted ducks being netted, consumed at banquets, and offered to the deceased. Appropriately, ducks are an example of mummified food offerings. Geese, on the other hand, were closely associated with important gods like Geb and Amun, who was referred to by the epithet “Great Gander.” (Compare this with the lowly sparrow, adopted as the hieroglyph for words like “small” and “bad,” the latter most likely because they ate the grain planted in the fields.)

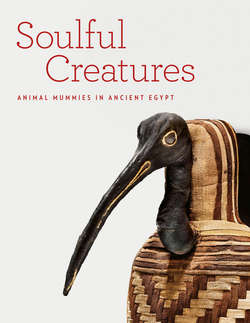

Ibis

There were several species of ibis in Egypt. The most commonly known “sacred ibis” (Threskiornis aethiopicus), with a white body, black neck, legs, and wingtips, and a dark bill, disappeared from Egypt by the middle of the nineteenth century c.e. (figure 40). This is the species mummified in huge numbers in the Late, Ptolemaic, and Roman Periods.