Читать книгу Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, Cleveland’s Free Stamp - Edward J. Olszewski - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

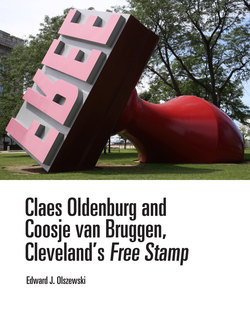

SOHIO, FREE STAMP, AND BP

In the design of Sohio’s new corporate headquarters in downtown Cleveland’s venerable Public Square, the company’s executives included the base for a work of sculpture which would stand at the left of a slightly sloping site as one entered the atrium of the building (fig. 5). The chief executive officer and chairman of the board of Sohio, Alton Whitehouse Jr., approved the design of a hand stamp submitted by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen in December 1982, and the sculptors presented a full prospectus with five drawings on June 22, 1984, which led to the contract of July 26, 1985.

Whitehouse’s choice of sculptors had been guided by the architect Gyo Obata and by Sherman E. Lee, director of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Lee first mentioned Isamu Noguchi to Whitehouse, then suggested Oldenburg as “an unconventional young sculptor.”1 Whitehouse’s initial exchange with the sculptor was informal, with the artist bringing models, plans, and drawings of some of his projects. The Philadelphia Clothespin appealed to Whitehouse, who always preferred the verticality and original location for the Cleveland sculpture.

Whitehouse had also been a trustee at the Cleveland Museum of Art, and his commitment to the arts in Cleveland was recognized by his election as president by the museum’s board of trustees on December 9, 1985.2 Shortly after Sohio returned to John D. Rockefeller’s original title of Standard Oil Co., the corporation was acquired by the British Petroleum Company, and Robert P. Horton was confirmed by the board of what would soon be BP America as its new chairman and chief executive officer. He replaced Whitehouse on March 11, 1986, and quickly announced that the commissioned sculpture was “inappropriate” and would not be installed.3 Because initial payments for the commission had been made and assembly of the sculpture begun, Horton soon suggested that the work be placed in another downtown location, even offering it as a gift to the city of Cleveland.4

Figure 5 Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, Free Stamp sited on model of Sohio Headquarters in Public Square, Cleveland, Ohio, 1983, wood and latex paint, 3-1/2 × 2-1/8 × 1-1/8 in. (8.9 × 5.4 × 2.9 cm). Courtesy of the Oldenburg van Bruggen Studio

The first hints that the project may have gone awry appeared in a Wall Street Journal article recounting the replacement of Mr. Whitehouse by Mr. Horton.5 The article, “Taking Charge,” had three subtitles, the last of which was “Huge Rubber Stamp May Go.” The story related how BP’s Sir Peter Walters had rallied board members in the ouster of Whitehouse, concluding with an allusion to the apt symbolism of the rubber stamp sculpture as reflective of the process in which all votes fell into line. Nonetheless, the decision to terminate the sculpture most likely had been made before the flip remark in the Wall Street Journal.

When the sculptors were informed that the installation would not go forward, they responded with a letter to Horton objecting to this violation of their contract as profligate, negating three years of design, engineering, and fabrication.6 They stressed the site-specific nature of the design not just for the atrium plaza of the building but for Public Square as well, underscoring that the work had been planned for the city of Cleveland and not merely as a corporate emblem. Like Picasso with his sculpture in Chicago (Untitled, 1967), Oldenburg and van Bruggen had donated their creation to the city of Cleveland, allowing the public to use the image at its discretion. The sculptors had made it a condition that the design be approved by the Fine Arts Advisory Committee and the City Planning Commission. Approval was given by both on August 1, 1985.7 Clearly, the city administration was in favor of the sculpture.

On April 23, 1986, Nick T. Giorgianni, director of property services at BP, wrote the sculptors’ contractor, Donald Lippincott, Inc., on behalf of BP’s general counsel, George J. Dunn, of the endorsement by the corporation of a new location for Free Stamp. This was reiterated to the sculptors in a second letter of the same date. A week later, Stanford Schewel, the sculptors’ attorney, responded by enunciating the principle that relocation of the sculpture would be equivalent to its destruction. Conceptualized by the sculptors as a work intended for a specific site, it would lose its meaning as a symbol of a hardworking city if it was moved. In his reply on May 1, Mr. Dunn expressed his disagreement with the notion of the hand stamp as a site-specific sculpture, and insisted once more that the work be relocated to a compatible site. He specifically challenged the idea that moving the sculpture would be equivalent to destroying it, asserting, “We have not heard that opinion from any others and, in fact, since we announced our intentions last week, there has been a great deal of interest from thoughtful people in the Cleveland community relative to a relocation of the sculpture.”8 But Helen Cullinan, arts critic of the Plain Dealer, in an article on April 25, 1986, had quoted Sherman Lee, who would not accept another location for the sculpture, as well as Joseph McCullough, president of the Cleveland Institute of Art and chair of the Fine Arts Advisory Committee of the City Planning Commission (which approved the design), who “strongly objected to a new location.”9 She had also stated the objections of Edward B. Henning, former curator of modern art at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Clearly, the arts authorities in Cleveland supported the sculptors’ position.

The business editor of the Plain Dealer, Ernest Holsendolph, made several perceptive observations based on his viewing of the maquette which the sculptors had presented to Sohio, remarking how “the sculpture that resembles a rubber stamp seemed imaginative, a clever counterpoint to the massive building, and a much needed touch of whimsy. It is probably destined for distinction, but none so glowing as it would have had.”10 He recommended a temporary installation in its original site for one month, suggesting that the viewing public and BP officials could come to neither full appreciation nor unequivocal rejection without seeing the sculpture in its intended setting. Given that the installation of the sculpture would have taken two months and thirty-seven tons of steel, and once in situ would have been a fait accompli, this was not a workable idea that the officers of BP could accept.

In spite of a rally in support of the installation of the rubber stamp sculpture by prominent Cleveland backers of the arts, held on the plaza of the BP America building on May 9, 1986, many viewed completion of the project as hopeless, and suggestions for alternative sites quickly followed.11 McCullough again urged Horton to keep the work in Cleveland, but now volunteered to help convince the sculptors of the merits of other locations.12 The mayor of Cleveland, George V. Voinovich, wrote Horton on June 19 to suggest Willard Park as a new home for the sculpture.13

Willard Park was a green area adjacent to City Hall with some trees, a small fountain, and a modest memorial to the city’s firefighters (fig. 6).14 The park was named after Archibald M. Willard (1836–1918), the painter of the famous Spirit of ’76. Known through many variants, a version of the original painting of 1876 was requested in 1912 by Mayor Newton D. Baker for city hall, where it is still on display in the rotunda (fig. 7).15 Not only were some members of city council against the site, but the sculptors also had reservations about a new location.

Figure 6 William Ward, Firefighters’ Monument, 1965, marble. Willard Park, Cleveland, Ohio. Photo by author

In April 1986, George Dunn solicited help from Evan H. Turner, who had succeeded Sherman Lee as director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, and Tom Hinson, curator of modern art, for the support of the art museum in arranging a new location. Dunn indicated his intention to notify Schewel and Lippincott, the sculptors’ attorney and contractor, respectively, of BP’s denial of the original siting.16 McCullough wrote Horton in June to reiterate that the Fine Arts Committee wanted the sculpture to remain in Cleveland.17 He again offered to help find a new location, and even volunteered to aid in convincing the sculptors of the suitability of a new placement, backing away from his earlier support of the work as site specific. In his response to McCullough, Horton, jockeying for an alternative location, conceded that “our city deserves a major work by an internationally celebrated contemporary sculptor” (as long as that “major work” was not situated at BP’s doorstep).18 He noted Voinovich’s suggestion of Willard Park, and volunteered that BP would pay for the installation.

Figure 7 Archibald M. Willard, Spirit of ’76, 1912. City Hall, Cleveland, Ohio. Photo by author

Evan Turner had earlier cautioned Horton that it was necessary to keep the attitudes of the sculptors in mind if any resolution of a new setting for the sculpture was to be had.19 He suggested the plaza west of City Hall as a possible site, or the plaza at Marshall Fredericks’ peace memorial. That August, Dunn wrote to Tom Hinson stating that if “left with the unilateral decision as to relocation and elect to go ahead on that basis, we would like comfort that the museum would assist us in carrying out that effort.”20

Figure 8 Claes Oldenburg, sketch for hand stamp sculpture, 1988. Photo by author. Courtesy of the Oldenburg van Bruggen Studio

On September 3, 1986, the sculptors, accompanied by their contractor, Lippincott, again visited Cleveland to consider the suggested new settings for the sculpture.21 Sites proposed included the football stadium; Willard Park, as first suggested by Mayor Voinovich in June; the corner of Ontario and St. Clair at the Justice Center; the Warehouse District, the campus of Cleveland State University; and Euclid at Huron on Playhouse Square. Three days later, Horton enthused to Turner, “I must say that on its side in Willard Park appeals to me. That way the ‘FREE’ could be seen and the image of a straight up-and-down ‘Rubber Stamp’ be substantially reduced. I believe that it is important that Cleveland receive this important work without thinking—however misguidedly—that the artist is poking fun at the city.”22 Horton was repeating the sculptors’ suggestion of a tilted placement for the sculpture, and with a new location it was apparently no longer sarcastic. A quick sketch from notes made by Oldenburg during the visit depicts the sculpture displaced from its pad at the right (fig. 8), and on the left, at van Bruggen’s suggestion, a sculpture on its side.