Читать книгу Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, Cleveland’s Free Stamp - Edward J. Olszewski - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6

IMPASSE June 1986 to September 1989

Every true work of art has violated an established genre, and in this way confounded the ideas of critics, who thus found themselves compelled to broaden the genre.

—Benedetto Croce, Estetica

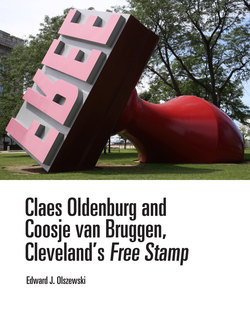

Behind-the-scenes activities to resolve the placement of Free Stamp began just weeks after Horton’s announcement of its rejection, and took place initially without the sculptors’ participation or knowledge. Indeed, the artists in their Manhattan studio would be unaware of much of the controversy provoked by local talk show hosts, TV commentaries, newspaper cartoons, and letters to the editor. The Cleveland Museum of Art issued a press release on September 6, 1985, announcing an exhibition, Sculpture in Public Places, which contained twenty-five works, including a model of Free Stamp.1 This was intended to remind the public of the rich tradition of public sculpture and to spur the authorities to facilitate the installation of Oldenburg and van Bruggen’s work. In July of 1986, less than a month after Mayor Voinovich had volunteered Willard Park, Evan Turner suggested to Horton a plaza space on the other side of city hall next to the county courthouse (Mall C).2 In the end, ten prospective sites were discussed, not all of which were brought to the attention of the sculptors and any one of which would have required their eventual approval. The chosen site would also have to be agreeable to Mayor Voinovich and Messrs. Forbes and Horton.

Evan Turner’s suggestion of Mall C was pursued by Dunn, who indicated that this location was problematic because it was the joint responsibility of Cuyahoga County and the City of Cleveland, and because of projected plans to build on it.3 Morrison explored its suitability by asking the city architect, Paul Volpe, to report on the mall as a setting for a monumental sculpture. He found that Mall C, an open green space, was also the roof for the Cleveland Convention Center, and that only one place, approximately at the center of the area under consideration, would be able to support the work, and only with buttressed foundations to carry the added weight of the sculpture. Morrison and Ed Richard, the mayor’s executive assistant, concluded from these observations that Mall C would not be suitable.

Now that the mayor had added Willard Park to the equation, Richard worried about convincing the president of city council, George Forbes, of its merits.4 A ten-month impasse ensued until Giorgianni wrote to Lippincott on January 26, 1988, to suggest the possibility of a harborfront location. This was long after Oldenburg and van Bruggen had visited Cleveland to consider other sites, and after they had made clear that a new location would necessitate a changed design. In the sculptors’ absence, city staff members prepared models from their new maquette, with the sculpture now lying on its side rather than upright. They explored the sculpture facing different directions on the East Ninth Street Pier (now Voinovich Park). The sculpture, although large, seemed lost in this open setting, and the Fine Arts Committee saw no context for it there. The North Coast Harbor, now the location for I. M. Pei’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, would have offered a changed visual backdrop for the sculpture but would not have identified it with the city in any significant way.

After six months, Giorgianni contacted Morrison about the prospect of a site on downtown’s Playhouse Square. Models of this setting were also prepared, but the location was vetoed by Developers Diversified, which was planning to build a hotel in the area. Donald Frantz, vice president of special developments, objected that “the sculpture evokes a business-type image which is not in keeping with the entertainment orientation of the theater district.”5 He added that the scale was wrong for the area, and volunteered a location near Huron and Ontario at the planned Gateway Complex, with its baseball stadium and coliseum.

It was as if Voinovich, Forbes, and Horton had voted as a bloc in approving each of seven other possible locations. In the old industrial Cuyahoga River Flats, the park at Settlers’ Landing was rejected; the small greensward would have been unable to accommodate the work in any case. Other ruled-out settings included the Warehouse District west of downtown and the campus of Cleveland State University. Public Square was also mentioned; Forbes suggested its northwest quadrant, which displayed a statue of former Cleveland mayor Tom Johnson. Neither Horton, nor the sculptors when approached, would consider this setting.

Finally, Willard Park was agreeable to Voinovich, Horton, and the sculptors, but Forbes objected. He found the proximity of the sculpture to city hall unsuitable, as Horton had found it “inappropriate” for his atrium plaza.6 Consequently, no decision for the relocation of the sculpture occurred for several years, due primarily to the intransigence of the president of city council, although council had initially expressed no objection to the sculpture for the Public Square site, and the city administration had approved it through its city planning commission.

Hunter Morrison understood the importance of Oldenburg and van Bruggen as world-renowned artists and was concerned that the city of Cleveland might lose their sculpture. He had invited them to view the new locations that had been recommended for the placement of Free Stamp. The sculptors considered the change of venue worth pursuing only if the situation of the sculpture could be redefined. It could not be the same work on another site. And from their point of view, these discussions no longer involved BP America. As noted, on September 3, 1986, the artists visited the city accompanied by their fabricator, Donald Lippincott, and met with Morrison, Giorgianni, Richard, and Turner.

The sculptors found the expansive mall associated with the new Crile Building by Cesar Pelli at the Cleveland Clinic campus unsuitable for lack of context. They also ruled out a setting near the Cleveland Museum of Art in University Circle, and the long drive at Play House Square facing the Byzantine Revival buildings of native son Philip Johnson. Horton had favored the Mall C location on Lakeside Avenue just west of city hall, between it and the county courthouse and on a direct alignment with the BP America Building. Oldenburg and van Bruggen expressed initial interest in Mall C, but they soon realized that the space was too large for Free Stamp, whether in its vertical format or as placed diagonally. Voinovich had kept an open mind about this choice, which, as noted, was eventually determined to be impractical, and is now the site of a new convention center.

During their visit the sculptors made clear that a new location would require a new design, and van Bruggen mentioned placement of the sculpture on its side.7 In his musings over the Willard Park site, Oldenburg made a sketch of the sculpture still in its vertical format, the park graded in the shape of a four-sided pyramid with the hand stamp at its apex. In his recollections after the meeting, combining sketches and written notes, he observed that the sculpture was too small for Willard Park if placed upright, even with the exaggerated pyramidal plinth, but noted that laying the work on its side offered several advantages. A horizontal orientation of a modified sculpture better suited the park. Placement of the sculpture on its side would free it from its pad, which would remove a constricting element in the rethinking of the sculpture. This would also obviate the need for redesign of the park, but if landscaping should be necessary, Willard Park would be suitable. Van Bruggen had added how the stamp sculpture would look as if it had been thrown. Oldenburg’s notes indicate that in this context the word “FREE” takes on the connotation of liberating the sculpture from its pad or base, from its confining architecture, and even from its reluctant patron. He also observed that placing the sculpture on its side was a way of emphasizing its history. It was now a sculpture rather than an architectural adjunct, and its new situation declared its independence. Although, in a sense, the work turned its back on the park, pedestrian and automobile traffic interacted more directly with it in its corner setting. Taking up van Bruggen’s idea of the sculpture as a “discarded object,” Oldenburg alluded to his drawings of 1965, the Proposed Colossal Monument for Central Park North, N.Y.C.: Teddy Bear, and Proposed Colossal Monument for New York Park: Teddy Bear (Thrown Version).

This notion of things topsy-turvy is a popular theme in Oldenburg’s early writings. In his thoughts on the nature of art in the 1960s, he wrote, “It’s more interesting if things are upside-down,” and of the Proposed Colossal Monument for the Battery, N.Y.C., Vacuum Cleaner, View from the Upper Bay, “I tried to accept the fallen position—just the form of it, without an explanation of why it was fallen (or thrown) as if a skyscraper had been constructed on its side, like a fallen tree, or leaning.”8 Thus Oldenburg and van Bruggen have closed the circle by offering the notion of the discarded object against the objet trouvé or found object of Picasso and Duchamp, such as the latter’s bottle rack, urinal, and snow shovel.9 Their new configuration for the sculpture added poignancy to Oldenburg’s statement recorded in his notes of May 1961: “I am for the art of things lost or thrown away.”10