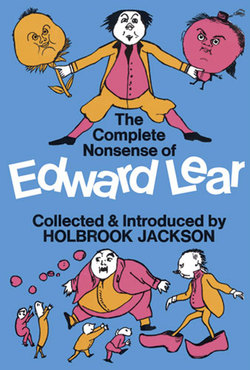

Читать книгу The Complete Nonsense of Edward Lear - Edward Lear - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

5

ОглавлениеNo more diligent artist ever lived. He had the concentration of a beaver and never liked parting with a job once he had started to gnaw it. During fifty years of his busy life, for instance, he made 200 illustrations for Tennyson’s poems, but did not live to see any of them published.1 Sometimes he suspected this laboriousness although he looked upon a ‘totally unbroken application to poetical-topographical painting and drawing’ as the ‘universal panacea for the ills of life’.

The number of drawings he turned out on a sketching tour was astounding. In one year alone (1865) his ‘outdoor work’ comprised, ‘200 sketches in Crete, 145 in “the Corniche”, and 125 at Nice, Antibes and Cannes.’ He goes to India and in six months despatches to England ‘no less than 560 drawings, large and small besides 9 small sketch books and 4 journals’. He was then sixty-two and described himself, with some justice, as ‘a very energetic and frisky old cove’. When not travelling in search of the picturesque or working up his sketches) he is holding exhibitions of drawings and paintings from the sale of which he lived, or writing to his friends and patrons about work in progress and the attendant economic problems which were never entirely absent, and any spare time was devoted to the diaries which he kept for years, and those travel books2 which he illustrated with some of his best drawings.

He lived to draw and paint and drew and painted to live, pretending to hate the necessity of having to go on day after day ‘grinding’ his ‘nose off’. But although he talked little of art as such, and affected to belittle his own inspiration, his artistry was more than technique and it is a criticism of criticism that his drawings, particularly those in black and white and water-colours, should have been sidetracked rather than assessed. His habit of under-statement, as in the case of Anthony Trollope, is responsible for some of the posthumous neglect of his graphic work. His trick of looking upon himself as a recorder and ‘topographer’ rather than a creator, has been taken too literally. Self-depreciation was not a pose. Lear was as puzzled about his gifts as he was about marriage, or, indeed, about life. Conscious of ‘being influenced to an extreme by everything in natural and physical life, i.e. atmosphere, light, shadow, and all the varieties of day and night’, he wondered whether it was ‘a blessing or the contrary’, but decided, wisely enough, that ‘things must be as they may, and the best is to make the best of what happens’. Like Pangloss he concludes that all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds and he certainly makes the best of this sensitiveness before the picturesque, grumbling much but demanding little beyond ‘quiet and repose’ so that he could get on with his work.

His idea of heaven is a place of charming landscapes without noise or fuss. ‘When I go to heaven, if indeed I go—and am surrounded by thousands of polite angels—I shall say courteously “please leave me alone:—you are doubtless all delightful, but I do not wish to become acquainted with you;—let me have a park and a beautiful view of sea and hill, mountain and river, valley and plain, with no end of tropical foliage:—a few well-behaved cherubs to cook and keep the place clean —and—after I am quite established—say for a million or two years—an angel of a wife. Above all let there be no hens! No, not one! I give up eggs and roast chickens for ever”.’