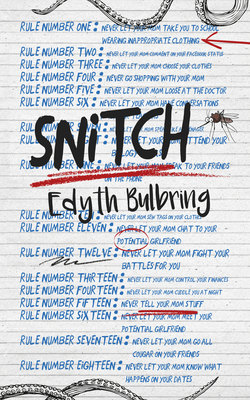

Читать книгу Snitch - Edyth Bulbring - Страница 4

ОглавлениеRule #1: Never let your mom take you to school wearing inappropriate clothing

The cars are backed up in the driveway going into the school parking lot. Mom looks at her watch and pulls a face. “Ag no, I’m going to be late. Can you see what’s going on up ahead?”

I stick my head out of the car window and peer along the row of stationary vehicles. A lunatic in a dressing gown is standing next to her stalled Mini Cooper, throwing her hands about in the air. A boy stands at her side, silently begging the ground to open up and swallow him whole. The earth says: you’re on your own. Suck it up, Loser.

“It’s Sizwe’s mom. Her car’s conked out.”

The Beemer behind us starts hooting. I turn around and see George’s mom, her face like a heart attack: “Come on, move it! I don’t have all day.” She mashes her fist on the hooter. George catches my eye and ducks down, looking for spare change on the floor of the car. Sorry buddy, too late. I already saw you.

There are three million and one uncool things parents do to their kids that make them want to shred their wrists. It’s not a good Friday for Sizwe and George’s wrists. Their moms are acting up big time. I count my lucky beans that my mom knows how to behave. She sits real quiet with her fingers tapping the steering wheel, her jaw just a little tense. Mom’s not one of those parents who hoots and shouts on the school premises, even when I’m slow.

Uncool parent behaviour stalks us before we take our first baby steps. It follows us as we learn those moves on the jungle gym, and dogs us as we race into primary school. This is the time we should learn to read the cruel signs pointing to what’s waiting for us when we crash into our teens. If we read the signs correctly, we’ll be forewarned and will be able to spend the next five years playing: I’m really an orphan, and who are those hyenas spraying the principal with beer outside the booze tent at the school fête? For sure, they’re not my parents.

Embarrassing parent behaviour starts the day we’re born – when they give us our names. The prize for sensitivity in this category goes to Mr and Mrs Brad Pitt from Hollywood who bunked their Grade Nine spoonerism class and named their daughter Shiloh Pitt. High five, parent Pitts!

Sizwe’s mom gave him a name he could live with. If only she could remember what she’d written on his birth certificate. She gets back into the driver’s seat as several guys horse around, pretending to push the stubborn Mini Cooper. “Don’t just stand there, Pumpkin,” she yells at Sizwe out of the car window. And poor Pumpkin kicks the car tyre and helps the other boys shove her to the side, allowing vehicles to pass.

My name’s Ben. Not Moon Unit, Blanket or Apple. (The runners-up from Hollywood in the shameful name category.) And my surname is Smith. Luckily not Dover or Ten. I was named after my dad who passed on when I was seven months old. Cancer. He didn’t die from a drug overdose or get brained by a coconut. No, my dad wouldn’t do that to me.

My sister’s name is Helen. Sometimes Hell-raiser, Hell on Wheels or Helluva Cool. Never Smellin or Melon. No one would ever dare disrespect my sister.

And there’s my mother. Her name’s Sarah. If you’ve got to have one parent, she’s the kind of mom guys should have. Her involvement in my school life is underwhelming but respectable. She does tuck-shop duty twice a term and library once a month. She attends parent-teacher meetings three times a year, and only comes to the big sports matches. She’s got two feet in my corner, but doesn’t hog the whole square. She’s present, but not in my face. The way moms should be.

Mom idles at the entrance to the school building while I collect my stuff off the back seat. She squeezes my hand goodbye and drives off to work. I pass Sizwe’s mom standing outside her car, punching numbers into her phone. The cord to her dressing gown has come loose and the whole world and my grade get to check out the butterfly tat on the top of her left thigh. Phwoar!

Smoke pours out of the Mini Cooper’s bonnet and water trickles from underneath the chassis, pooling on the ground. Sizwe’s mom gives up on her phone, tossing it back into her handbag. She sees me. “Oh Ben, can I borrow your cellphone? Sizwe always has airtime, but he’s disappeared.” Yes, Pumpkin has found his happy hole in the ground.

I don’t have airtime. Or a cellphone. I’m going to get one when I turn fourteen. I’ve still got five months to wait. I tell Sizwe’s mom I’m not connected. She shrugs, tightens the cord around her dressing gown, and does the walk of shame past thirty guys towards the secretary’s office, where she can beg the use of a phone.

She spots Sizwe playing hide-and-seek behind the recycling bins. “Oh there you are, Pumpkin. Walk with me to the office so I can call the garage.” Sizwe freezes, then takes a phone out of his blazer pocket and pushes her back in the direction of the abandoned Mini. If we laugh, he’s going to punch our faces in later.

There’re a dozen and a half rules kids should know by the time they hit their teens. Simple rules of survival like: never let your mom drop you off at school in her dressing gown – a small detail Sizwe overlooked this morning. These rules are common sense. Like all teenagers, I know them. And Mom does too. It’s why I trust her to be cool.

I find my best friend Tsietsi at his locker, emptying his satchel and collecting the books he needs for school today. “You there, Tits. Got a spare pen for me?” some guy yells. See – Tsietsi’s parents also sinned on his birth certificate. Along with the parents of guys in my class called Richard and Fanus, who will end up living and dying as Dick and Fanny.

“Hey, Ben-dude,” Tsietsi says, scratching the festering bites on his arms. He’s covered in them. If there’re seventy million people in a room with Tsietsi and one mosquito, it will zone in on Tsietsi. He’s a total bug magnet. His mom used to send him to school covered head to toe in pink calamine cream. This year he rebelled. No more calamine. But if you ignore the itchies, Tsietsi’s OK. He’s my best friend and I’ve known him all my life.

My other best friend’s name is William – you can work it out, his parents also carry the cursed naming gene. I’ve known him as long as Tsietsi. I could never choose between them. But I’ve got lots of other friends. I’m reasonably popular with the rest of the grade. Just not too popular to get dumped when a cooler guy hits the quad.

William opens his lunchbox and lifts a piece of folded paper from under the packet of jelly babies like it’s a used piece of bog roll. He doesn’t read it, but crumples it up and chucks it in the back of his locker. But I know what the note says: Sweets for my sweet. Hug-hug-hug. Or maybe today it’s: Jellies for my baby. Kiss-kiss-kiss. William’s mom has a thing about lunchbox notes. It comes from a good place, and she’s a lovely human being. I’m just glad she doesn’t belong to me.

I get through the day’s maths and history tests without breaking too much of a sweat. After school, I meet

the rest of the guys on the rugby field where Sir announces the players for the teams in the big tournament tomorrow. I’m playing reserve in the junior team with a bunch of other guys from the lower grades. No problem: last week I made it onto the team and nearly scored a try.

See, this is how I roll. I’m just regular Ben Smith from Joburg, the city of mine dumps and electric thunderstorms at the bottom of Africa. I do well at school and sports, but not too well. I’m not too tall, and I’ve got a respectable amount of zits. I’ve got a mom who’s cool and doesn’t make scenes or kiss me outside the school gates – just that hand-squeeze safely inside the car.

I’m one of the lucky kids. There’re only about three hundred of us in the world, but I’m guessing, because I’ve never met them. I only know the unlucky ones. Those who develop acute auditory deprivation when their moms scream up the school corridors for them to take their fingers out their noses: “Worms! You’ll get worms if you pick and eat.” Yes, me and fifty-two other guys get to hear this.

“It’s an important day tomorrow. Make sure you get enough sleep and take your vitamins,” Sir says. He points an “I’m talking to you” finger in the direction of the older guys who play in the senior team. Tomorrow we’re playing the boys from Voortrekker High. These guys make gargantuan look like a small word. They’re super-sized. Every one of them is built like he’s pulled an ox-wagon single-handed across Table Mountain. We’re going to get murdered.

“Tell your parents about the tournament so there’s a big turn-out. We’re going to need all the support we can get,” Sir says. This info goes in the ears of half the guys and straight out where it’s dumped in the trash with the other things not to tell your parents. When they come to matches, the dads argue with the ref and the moms run hysterical onto the field when our teeth get kicked in during the tackles.

But I’m not worried about telling Mom about the tournament. If she makes it to the game, she’ll sit calmly in the stands and never dream of causing a scene. Even if I get to play and score a try.

For sure, I can tell Mom anything. And she listens and never judges. Because Mom knows: what Ben tells you in the kitchen stays in the kitchen. It allows me to break the most important rule teenagers know: never tell your mom stuff.

I break this rule all the time. But shoot me now, I should have known. Because I was warned thirteen years ago when I first started crawling and getting into people’s stuff. Sometimes when you break something, it can’t get fixed. Not ever again.

I broke this rule one too many times. And Mom opened her mouth and blabbed. Then I wasn’t Ben, Benno, Ben-dude anymore. I was the rat, the weasel, the sneak. No longer Ben-OK. I was Snitch.