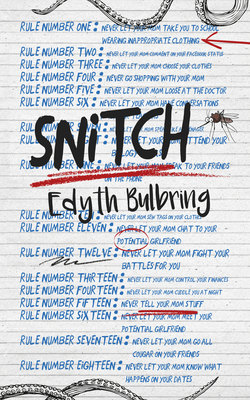

Читать книгу Snitch - Edyth Bulbring - Страница 5

ОглавлениеRule #2: Never let your mom comment on your Facebook status

Terror rips a chunk out of my tracksuit sleeve when I walk through the front door. It’s the way she greets me every day when I get home from school. She’s real affectionate like that.

Terror is Helen’s dog. Helen is three years older than me and has blue dreadlocks. Everyone in my school thinks she’s super-chilled. I do too. I couldn’t have pawned my soul for a cooler sister. She pretends I don’t exist in public, and only ever speaks to me when she wants something. Like, “Hey Smith, buddy, if you give me your lunch money, I’ll let you wash the dishes for me after supper.” See, she’s brilliant.

Helen attends the girls’ school next door to mine. St David’s for me and St Anne’s for her. Our schools are twinned by millions of years of history and tradition. And we share the tennis courts and the chapel. Although the holy grail of most of the guys in my grade, second to being invited to a private twerk show by Miley Cyrus, is to share their saliva with the St Anne’s girls. Any one of them will do.

I only want to share my walks home from school with one St Anne’s girl. Her name’s Elizabeth and I haven’t allowed myself to even dream about the saliva thing yet. Elizabeth lives four blocks down the road from me, and she is a goddess. Most days, she allows me to walk twenty steps behind her. But I sense a softening in her attitude.

Last week she looked back over her shoulder before going into her house. I ran panting to see what she wanted (anything, I’ll do anything). She said, “Oh, it’s only you, Stalker.” I told her she could also call me Ben. Or Benno if she liked. She said she liked Stalker just fine.

Helen’s already home. She rides to school on the motorbike she got on her sixteenth birthday. Mom sometimes manages to pick me up from school if she’s not too busy at work, but most days I tell her I enjoy the fresh air and the exercise. (And the view of the back of Elizabeth’s head.)

“Don’t tease her, she’s not in the mood,” Helen says, clicking her fingers at Terror, who spits out a piece of my tracksuit and attaches her fangs to Helen’s hand, chipping her black nail polish. (She doesn’t quite manage to amputate Helen’s arm at the wrist.)

The thing about Terror is, she’s never in the mood. She’s the most bad-tempered dog ever spawned from Satan’s own loins. She hates everyone except Helen. And she despises me in particular.

Helen got Terror as a birthday present from Uncle Charlie a few years ago. He told Mom, please don’t be cross. “I know it’s a gift you weren’t expecting. But isn’t surprise the true meaning of birthday presents?” And no, he couldn’t take it back to the pet shop.

“A pure-bred Jack Russell,” Uncle Charlie said. But Terror grew impurely, lifting a leg on her certified breeding certificate. She now looks like the sum of all the bits and pieces of the stray dogs we find sniffing on the pavement.

Helen maintains Terror doesn’t like boys. “It’s your smell,” she says. My sister’s right. Mom used to say I smelled like the Angel Gabriel’s own sweet breath. Now she asks if I’m sure I’ve brushed my teeth in the last two weeks.

“And are you showering as regularly as you should, Ben?” I expect it’s a sign of the ageing process. My smell changed when I turned thirteen and got my first armpit hair. I’d morphed into a normal stinking teenager. Hallelujah!

Ten minutes later, Mom gets home with Uncle Charlie in tow. He’s the one who wishes he could squeeze the middle of Mom’s toothpaste tube if she ever figures out Dad’s never coming back. Uncle Charlie pants around the edges of our lives like a dog hoping for a walk in the park. (Not like Terror, who doesn’t like walks, or ball games, or me looking at her.)

Uncle Charlie wears his chinos too high up over his stomach and tells the worst jokes ever. Fine by me, he’s not my dad, so it doesn’t matter. He’s a funny-man by trade, a one-man-show comic act. Jokes are his bread and butter. Most months the bread is dry, like the pecks Mom allows him to give her cheek when she sends him home, his tail between his legs.

“The chances of you dying of botulism if you eat that rubbish are thirty-seven per cent,” Mom says, sniffing at the takeaway spicy chicken wings Uncle Charlie’s clutching to his chest. “They use the oil at least a hundred times. You’ll be taking your life in your hands with just one bite.”

Mom’s a number-cruncher for a big life insurance company. She’s got life-threatening stats at her fingertips. She knows if you swim in the Indian Ocean during summer, there’s a seven per cent chance you’ll have your leg ripped off by a Great White. Chilling on the beach means a twenty-one per cent risk of being christened by a seagull. Not going near a beach and staying out of the sun decreases the odds of getting cancer by eighteen per cent. (If you don’t smoke, hang out in traffic jams in rush hour or guzzle carcinogens.)

Mom likes to live as risk-free as possible. She keeps a strict vegetarian fridge (avoiding all those health-threatening hormones they pump into the meat) and only wears flat heels (defying the fourteen per cent certainty of breaking her neck). The only concession she makes to risk is drinking tap water. Because everyone knows bottled water is a bloody rip-off. See, I said bloody. I’m allowed.

I’m permitted two swear words a day. “Swearing is a normal developmental milestone,” Mom says. But every time I go over my quota, I have to put five rand into a jar. (Although this seldom happens because I’m useless at swearing.) At the end of the month, Mom takes the money and buys food for the desperados who hang around outside the bottle store at the mall: “If you give them money, there’s an eighty per cent chance they’ll just drink it.”

She defines swear words as those identified as profanity in the Oxford dictionary. These include words “describing a part of the anatomy or a bodily function used out of context, in inappropriate combination or with the intent to insult or cause offence.” (Mom and Mr Oxford’s definition.) For example, I wouldn’t get fined five rand if I said the old man had an operation on his sphincter. But if I called someone sphincter-breath, that would get Mom shaking the jar.

Mom makes a salad (washing the lettuce twice), puts the mac cheese in the oven (no radiation from a microwave for us) and butters some rolls (fresh). She’s looking a bit hot and bothered.

“Why so flushed?” Uncle Charlie says. It gives him a chance to trot out the tragically funny punch-line: “Said one toilet to the other.” (Groan.)

Mom frowns at Helen and taps her fingers on the edge of the kitchen counter. “You unfriended me on Facebook today,” she says. Yes, Mom’s miffed. No one likes getting dumped in the full glare of social media. “I thought we agreed that if I allowed you to go on Facebook, I would always have access.”

Mom knows the risks of Facebook. Seventeen per cent of Facebook users are untrustworthy predators, and growing. The chances of one of them slitting her daughter’s throat at a dodgy rendezvous on the pretext of a New York modelling contract are four per cent. Mom likes to keep her children safe.

Mom was my third friend (after Tsietsi and William) when I got my Facebook account this year. She gets to see stuff like: Hey Ben-dude whassup? Chilling. Going swimming later. Have you done your maths homework? Personal stuff like that. I don’t mind. Mom knows not to comment or to try and make friends with my friends. And she never tags me in old baby photos.

“That’s blinking fascinating,” Helen says, keeping her head down, ignoring Mom, who’s waving the five-rand jar in her face. Helen maintains blinking is defined as an intensifier, not a profanity. So she can’t be blinking fined. Helen swears all the time. She says she’s prepared to pay for her pleasures. She’s tapping away on her phone, listening to music on her iPod and watching a movie on her iPad. She’s an ace multitasker.

“I killed a lot of friends today. It was probably a heinous mistake,” Helen says. She repeats the word heinous, rolling her tongue around it in a slow drawl so it sounds like a part of the anatomy. She often does this kind of thing to jerk Mom’s chain. Sometimes it’s funny, but it often makes Mom sad. Then I get mad at Helen.

“Stop it, Helen. You’re pushing your luck. And don’t tell me unfriending me was a mistake,” Mom says. We eat mac cheese and salad while she and Helen fight it out. Uncle Charlie eats his chicken wings and declines all offers of salad. “I’m a vegetarian. I love vegetables too much to eat them,” he says. (Ho-hum.)

The problem with Mom and Helen is that there’s no trust. This is what Mom says. Of course she understands that teenagers need their space. “It’s a normal developmental milestone for young adults to distance themselves from their parents and assert their independence. It happens with eighty-four per cent of all teenagers.” Mom looks at me with soft eyes when she says this, because I’ve escaped this stat so far. Mom and I are as close as we were fifteen seconds before the doctor chopped my umbilical cord.

The score so far in the fight between Mom and Helen is zero – zero. Because Helen chooses only to engage virtually, and Mom can’t score when she’s playing alone. “Is there something happening at school that you don’t want me to know about?” Mom finally says to Helen.

“The big rugby tournament’s on tomorrow,” I say. “I’m a reserve for the junior team. Are you coming to watch?” I like to run interference in their fights. Sometimes this distracts them, and then we can all move on and eat dessert (organically grown fruit) in a semi-peaceful environment.

Helen clicks her fingers under the table and Terror tears a hole in my sock. “Good girl,” she says. Her glare tells me I’ve said the wrong thing, and she’ll give me a Chinese bangle when she gets me alone later.

“That blinking dog,” Mom says, moving her feet to the side of her chair. “How much longer do we have to put up with her?” She looks at Uncle Charlie, because it’s all his fault we have a flesh-eating dog in our home.

Terror’s medium in size, which means her life expectancy should be nine years. At her last birthday, I started counting down, looking for positive signs of mortality. But the last time we took her to the vet (“You’ll be pleased to hear it’s not terminal, just fleas,”), he said there were at least another ten years in her. It’s not a good time to remind Mom of this.

“How do you make an egg-roll? Uncle Charlie says, biting into the crusty part of his roll (with butter). He’s also skilled in running interference. Especially when the topic of Terror comes up.

“Not now, Charles,” Mom says, so we don’t get to hear the punch-line: Push it over. (Howl.)

After supper, I get my computer and try to access my Facebook page. I’ve forgotten my password again – I’m not one of Mr Mark Zuckerberg’s most loyal customers. I like to keep my interactions with people personal. On the third attempt, I remember. The hole in my sock reminds me: Terror. That’s my password. I look for Helen among my eight hundred and fifty-two closest friends. I’m chuffed to see – Hellcat the Hellraiser and me are still tight.

There’s a lot of buzz about tomorrow’s rugby tournament on Facebook. “Don’t forget to take your vitamins, team,” the captain of the senior squad has posted. The word vitamins is in inverted commas and is followed by a smiley face. Every member of the senior team has given this status a like. Fourteen likes.

There’s only one comment. It’s from my sister. “Hey zitheads, your balls are gonna shrink.” Between you and me, this is not the kind of morale-boosting behaviour we look for from the St Anne’s girls. And Hellcat the Hellraiser has added a frowny face. She doesn’t like the captain’s status one bit.