Читать книгу Waiting for a Wide Horse Sky - Elaine Kennedy - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSix

Amos was waiting with Olga at Friday’s when Marilyn and I arrived. Marilyn was still grumbling, half under her breath, about Myong-Ai’s nosiness.

Amos was obviously pleased to see us. Marilyn had already filled me in on what had been happening with him. He had been given a share apartment with other English teachers: one of the ‘instant married’ couples from Ireland, who had only met since coming to Korea. They had since decided that they couldn’t stand one another but never-the-less were not going to take the chance on being placed with families as Marilyn and so many others had been. So Amos had been living in what he called a war zone. Screaming rows happened every night. Although Amos had his own room, he was always tripping over whichever of his flatmates was sleeping on the lounge room floor.

‘I couldn’t believe my luck when Olga phoned and asked if we would be interested in going to Busan for four days over Chuseok,’ I said as I slid onto a long bench beside Olga. ‘I really need to get away for a while but it didn’t seem likely. Apparently Koreans not only go back to their family homes at Chuseok but they also book out every hotel in the country. Will you be coming with us, Amos?’

‘Hardly … three ladies in one room with four futons! I’m thinking of coming down for a day, though. I need to get out of the apartment before I go postal.’

‘Yes, I heard about your feuding room-mates. It sounds horrible. We all seem to be having trouble with accommodation. What about you Olga?’

‘I’m tempted to go back home.’ Olga said. ‘Marilyn told me about the letters you’ve written. I think Amos and I should do the same.’ She turned to Amos and explained that Marilyn and I had written letters of complaint to the Education Ministry and the Australian and American embassies complaining that our contracts were not being adhered to.

‘Would you really think of going home?’ I asked. Olga shrugged and grinned but didn’t give any further explanation.

Marilyn pointed at the three of us with the menu. ‘I’m telling you it is absolutely essential that we make formal complaints. As soon as there is an answer we need to go to Seoul and discuss this personally. I’m so angry at the way we’ve been treated.’

We were interrupted by the waitress. Amos then tried to change the subject.

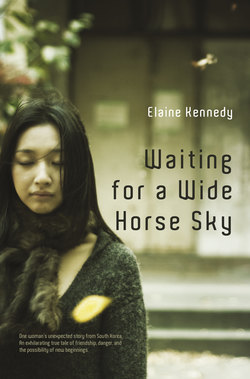

‘Aren’t we supposed to be all happy and excited about Chuseok? You know, blue horse skies and all that.’

‘Wide horse sky,’ I corrected him.

‘You know about that, do you?’

‘You bet! Myong-Ai likes to clue me up on Korean culture. It comes from the saying The sky is high and the horse is fat.’

‘Which explains everything,’ said Amos, rolling his eyes at me.

‘Well it does explain why we are sometimes getting blue, cloudless skies instead of grey all the time, now that we’re getting close to Chuseok.’

‘What about the fat horses. Seen any lately?’

‘You idiot,’ I laughed. ‘It’s an ancient saying from the days when it was a sign of prosperity that the animals were well fed. Also the blue skies meant that travelling to reunite with family would be easier. So Chuseok is the time when everything changes for the better.’

‘Let’s hope it works for our accommodation problems,’ said Olga.

‘There’ll be another big change for us anyway,’ I said. ‘After Chuseok we start at the Teacher Training Institute. I’m looking forward to that. We’ll find out what it’s like this Wednesday, when we start our orientation at the institute. I think it will be all of us. Is that right?’

The others nodded, with mouths full of Friday’s’ ‘buffalo wings’ and salad. Olga held up a finger to show she wanted to say something when she finished swallowing.

‘I’m so looking forward to three days without being at the school with Jun ignoring me. It is three days isn’t it … Wednesday through Friday?’

We nodded.

‘It’s such a relief. I’ll be leaving early in the mornings, too, before Jun is up, and then coming back late.’ She laughed in her husky voice. ‘It might be enough to save my sanity.’

I was quite excited when Wednesday came around. I had a three kilometre walk to join the chartered bus, so I left home early.

During the hour it took the bus to reach the institute, high in the mountains around Daegu, I was plied with questions by the Korean teachers. There would be other western teachers, my friends among them, coming from other directions, but I was the only one with this group.

My first sight of the Teacher Training Institute filled me with awe. It was the only sign of civilization in an immense landscape ringed with mountains. Long flights of marble steps led to the building itself, with a covered pavilion half-way up, which reminded me of a Greek temple. The walk from the bus parking area left me breathless. A few others among the group felt the same. While the younger ones continued on, a few of us rested on the stone benches of the pavilion and got to know each other. One of the Korean teachers that I had spoken to briefly on the bus, introduced herself as Yu Un-Kyong, and we discovered that we lived near each other.

‘I’ll be driving here tomorrow. I have a trainee teacher observing my classes these days. She’ll be doing the intensive training course here so she’s included in tomorrow’s orientation – and Friday, of course. Today is only for graduate teachers as you know. So, since you don’t live far from me, you could come with me to save such a long walk and leaving home so early. I’d like you to meet Sun-Hi.’

I thanked Kyonga, as she had asked me to call her, and made plans to meet her in the morning.

As we started to walk further I heard Marilyn call my name and waited while she caught up to us. I introduced her to Kyonga and we found seats together in the great hall. There was a lot to take in, with several lecturers giving information on the purpose and aims of the program. I took masses of notes so I could digest it all later. It was all well organised, and I was confident that I would feel relaxed and enjoy working here.

At morning-tea break I sat with Kyonga and three of her friends. I’d already caught sight of Robert, who, it seemed, had not been sent to Seoul. Olga and Amos were listening to his usual complaints with glazed eyes and I decided to stay where I was.

‘Tell me about your trainee, Kyonga. What was she doing before? Was she teaching?’ I asked.

Kyonga included the group around us as she filled me in.

‘No, Sun-Hi is an English-language graduate but until recently she was working in the head office of a group of factories. She was unhappy with the way the factory workers are treated and this new program is giving her an opportunity to change careers. The retraining will be intensive but short. I think she’ll make a good teacher. She cares about people very much.’

‘What was happening with the factory workers that made her so unhappy?’ I was curious and couldn’t resist asking.

‘She will tell you herself if you ask her tomorrow. She won’t mind. The workers are brought in from other countries, very poor countries, and they work for very little pay. In the factory where Sun-Hi was working they are all women from the Philippines and they are exploited shamefully.’

‘She’s told you a lot about this?’ One of the Korean teachers asked Kyonga.

‘I already knew. I used to do the same job, working in the office of a different company. I also left and retrained as a teacher, myself. I had to do the regular college course, though. This opportunity wasn’t available then.’

Sessions were recommencing and we were called back to the main hall.

Next morning I was waiting at the arranged place when Kyonga pulled into the kerb. Sun-Hi introduced herself and was keen to talk about the problems involving the migrant factory workers.

‘I was so glad when I was accepted into this program. It gave me the chance to get away from all of that,’ she said.

‘It must have been awkward, trying to help when it would be going against your boss,’ I said.

‘Well, no. I didn’t do anything to help, I was afraid of losing my job.’ She looked embarrassed. ‘I pretended not to notice that anything was wrong. Locking away their passports was one of my jobs. I used to lie awake at night wondering how I would feel.’ She was quiet for a moment and then said, ‘The conditions they live under – something has to be done …’

She hesitated again, obviously quite affected by what she was telling me.

‘I just thought that this opportunity was a way of doing something different and forgetting about the problems of these people. I didn’t see how I could change things, anyway.’

‘You’ve changed your mind about that, have you?’ I asked.

‘When I started working with Kyonga Sonsaengnim I faced the fact that I must do something to help or always feel bad about myself. She’s the first person I’ve ever met who does something for these people – apart from Angela, that is.’

She looked at Kyonga who smiled encouragingly and said, ‘You had already been doing a lot, Sunny … helping Angela to find her friends for instance.’

‘Angela insisted from the start …’ she started to say and then realised that I needed to know who they were talking about.

‘Angela came to work in our office about six weeks ago. She is a Filipina, too, but she is a university graduate and came here under a different arrangement. She has the same salary as I did, and Yuri the other office girl does, and she keeps her passport … much different from the factory workers’ conditions.’

Sun-Hi paused and Kyonga told me more.

‘Angela could have an easy life here but, on the plane coming from the Philippines, she met some older women, Filipinas. She worries about them a lot and, even though she knew that the two managers were not happy, she found out where they were and goes to see them when she can. They work in another branch of the company. It’s quite a distance away so Sunny has gone with her to help.’

I wanted to hear more about Kyonga’s part in this.

‘How do you go about helping these people, Kyonga? You must be busy with teaching. Do you go to the factories after hours?’

‘I can’t just go and ask who needs help. It’s a huge problem throughout Korea these days and the factory managers don’t want any interference. We have to be very cautious. In the first place there needs to be someone who is a friend or relative of one of the workers – like Angela, to introduce us and then, if they request help, we do what we can without drawing attention to ourselves.’

‘We? Do you mean you and Angela?’ I asked.

‘No,’ She took her eyes from the road momentarily and smiled, ‘No, I haven’t met Angela yet. I know about her and what she is trying to do from Sunny. I mean the group I have connected with recently from all over South Korea. It can sometimes be hard – fitting in work and meeting with people – sorting out problems.’

Traffic lights held us up for a couple of minutes.

Kyonga explained further that it was only since Sun-Hi had been observing her classes that she had learned about Angela and the women she was so anxious to help.

‘It was difficult for Angela to make contact with these women for the first couple of weeks. As new employees they were under restrictions at first, and then the gatekeepers would only allow us to come to the gate to speak with them there – Sam and Yuri, our work-mates, came with me to help Angela,’ Sunny added.

‘They talked to Angela about their problems through the gate, but were not allowed out. We’re hoping that will change very soon,’ Kyonga said.

‘But you have made arrangements to meet Angela though, have you, Kyonga?’ I asked.

‘I needed a reason to contact her. Now, since Sunny has been away for a while, I can use the excuse of driving her to see her old work-mates. I hope to make a time to talk to all three outside of work.’

I wanted to know more but we were nearing the institute and the road was narrow and winding. Kyonga was silent as she concentrated. Pulling into the parking area she turned to me and said, ‘Angela needs a lot of support herself. She’s putting herself in a dangerous position. I wonder if you could spare some time to come with me to meet her if you’re not busy on Friday – tomorrow evening. But maybe I’m asking too much of you. I’m sorry.’

I told Kyonga that I would be happy to join her after Friday’s sessions.

‘Thank you. I know you’re busy but I’m worried about Angela. There’s something she’s not telling us. She has a nasty wound on her face, Sunny told me, and she doesn’t talk about it. She might open up to you.’

We made arrangements later that day.