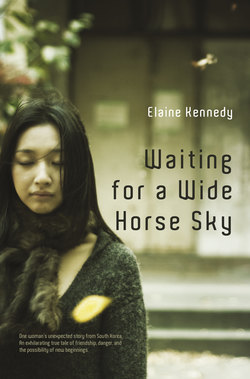

Читать книгу Waiting for a Wide Horse Sky - Elaine Kennedy - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеOne

‘Why would anyone want to go to Korea to work?’ With a disdainful sniff the uninterested speaker gazed over to a group on the other side of the room. It was 1997 and I had been back in Sydney for less than a week but this sort of comment no longer surprised me. I would rather have been home getting over jet lag than at this party, where I knew almost no one. Since the attention was now off me, I allowed my mind to wander.

I saw myself and two companions on a track winding upward through thick woodlands. We came across a clearing and the awesome sight of the ancient Haeinsa Temple, built into a mountain with a high flight of stone steps lifting it up. It seemed like an apparition that might melt and dissolve if we didn’t approach quickly enough.

I tried to give the appearance of fitting in with the small group in the far corner of the room but I was ignored. The simple but well cut, black cocktail dress I’d had made in Seoul was elegant and should have made me feel poised and confident, but it might just as well have been a hessian sack.

Without registering much of the conversation, I managed to give occasional encouraging nods while sipping slowly on my cocktail, conscious that I would need to be sober enough to drive back to my apartment as soon as the chance presented itself. This must be the reverse culture shock I had been warned against. There was no problem with language or customs but it all seemed trivial and alien. I had come back to a place where women over fifty are invisible. I returned to my daydream.

We stood on a cleared plateau, surrounded by mountain tops. The air was chill and clear, and the intense colour of the blue snow-capped mountains and green vegetation seemed surreal. Snow lay like sifted icing sugar on the ground and so quiet and deserted was it, that it seemed unimaginable that a busy community functioned behind the temple façade. The narrow steps were covered with ice at their inner edge, so I needed to take each step slowly and turn my feet slightly sideways. The climb seemed interminable and my heart pounded from fear of slipping. I dared not look back, then, finally, reached the top and the ultimate calm and peace of the dimly lit interior. A monk approached and welcomed me and my two companions, leading us to an open courtyard where we sat on stone benches and drank the green tea that was offered. Leading off the courtyard were entrances to the cave-like rooms and passages from which monks came and went, going about their business in their own secluded world.

This flashed through my mind almost instantly as memories do. As I refocused on the present party scene I realised that my companions were starting to drift away. It was a good chance to leave.

The centre of the Korean flag is the yin and yang symbol, the ubiquitous opposites, and this symbol seems to me to sum up my experiences in Korea and perhaps Korea itself. Driving home that night, further images imposed themselves on my mind. Vivid foliage in the autumn and waterfalls turned to ice in the winter. Children sliding on boards across an iced-over lake. Exuberant university students sitting around makeshift fires and singing to a guitar accompaniment or dressed in colourful costumes and performing traditional whirling farmers’ dances.

The other images came unbidden: the suicide of a Filipina factory worker; the mutilated hand of another, with little compassion shown by those responsible. Then memories of the generous people who made it their business to help. There had been many lessons to absorb. There was no reason to expect people who had never had these experiences to know or even be interested.

I thought about the way that the reasons for choosing to work overseas are at times hopelessly optimistic but often very sad. For many young people it is purely adventure. Having established their career they enjoy the chance to work in a country where they are accepted as experts – foreign experts – as their visas describe them. Older people, who have had to comply with compulsory retirement-age limits, take advantage of the chance to continue the work they love. For others the reasons are truly tragic. For one person it was the need to escape the memory of his whole family dying in a house fire. The glib criticism from those who don’t understand can be hurtful to say the least. For some reason there is often strong disapproval of those who choose to work overseas as if it is a shameful rejection of their nationality.

I had come to Korea as part of an initiative to prepare Korean teachers to introduce English language study in the early years of schooling. Appropriate methods of teaching young children were to be introduced in courses, which we would teach, at teacher training institutes. The graduates would then be equipped to facilitate an earlier start to studying English. With the rising economy of Korea at that time, being able to use English effectively was an increasingly important skill for participating in the international market.

All of us would also be assigned to a middle school, where we would work with teachers of older children and demonstrate western methods. There was, inevitably, occasional friction when instructing people who disagreed with the new methods, and who may have been practising their profession for a long time, but mostly objections were easily overcome.

‘Why would anyone want to go to Korea to work? How then could the question be answered? Why would anyone want to put themselves through the difficult, yet extraordinary things I encountered? I still don’t know and perhaps I can only begin to understand by telling you about what happened. This is the strange but true story of how I went to work in Korea and how it changed my life forever.