Читать книгу Call Me True - Eleanor Darke - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

A STRUGGLING WRITER

1930–1931

True couldn’t have chosen a worse time to leave a secure position; just as the Canadian economy slid into the decade-long “Great Depression”. All began well. She was hired almost immediately by the Canadian Federation of University Women as the Managing Director of their Vocational Bureau to “help university girls find their niche in business life.”1 The Bureau supported itself from the fees that it collected for filling a position, but, at a time when thousands of experienced men were unable to find work, the Bureau soon found it impossible to earn enough fees to continue and was closed in July 1931.

Her reference letter from the Convenor of the Vocational Committee responsible for the Bureau noted that True had “carried on the work in a splendid manner. She has the qualities of insight, understanding, and objectiveness necessary for vocational guidance, as well as those of initiative and executive ability which must be part of a successful director.”2 A less formal letter sent to True by all of the members of the Vocational Committee, thanked her for her work and noted that “With very little renumeration, and no immediate prospect of any, you have cheerfully and successfully carried on through a time of unprecedented business and economic depression. We feel that this has been a particularly fine and unselfish achievement.”3 I suspect from this that in her work at the Bureau, True had found, at least briefly, the calling she constantly sought. Many years later she quoted Dr. Robert McClure as saying that you don’t need money, “but you do need to be useful.”4

The pain of losing her position at the Vocational Bureau was moderated by the thrill of winning the first prize in the annual contest of Canadian writers of the Women’s Canadian Club. In April 1931 she was awarded its $100 prize in a ceremony in the concert hall of the King Edward Hotel. This was a major award. It was only the second time in eleven years that the Club had offered its prize for poetry and True defeated 190 other contestants from as far away as Siam to win. Stories about her win appeared in all of the major Toronto papers.

The poem, “Muses of the Modern Day” was, she said, “designed to meet the contention of many that modern subject matter did not lend itself to poetry.”5 According to a newspaper account she said “with much modesty” that winning the prize “had given her the most thrilling moment of her life.” The same article also noted that “she had written poetry since she was five years old, but it was not until a little over a year ago that she submitted any for publication” and quoted her as saying “It was not until after I left the publishing company that I had courage to submit my poetry for publication. I had been subdued by the horror of being one of those awful persons whose perpetrations editors dread.”6 True continued to regard herself as being first and foremost a writer for the rest of her life. Charlotte Maher told me that True always “saw herself as a researcher and writer. What she was, was one terrific politician, but that wasn’t part of her image of herself.” Doris Tucker remembered a time when all the municipal candidates had to list their occupation. True first wrote down “Mayor” but, when Doris told her she couldn’t do that, changed it to writer. In a column written after her retirement from politics, True talked about how after leaving public life she had moved “into the field of study and writing, where I [have] always felt I really belonged.”7

Encouraged by the win, True succeeded in having several poems published that year. She wrote a number for articles for various publications, including The Canadian Forum, The New Outlook, and The Globe and Mail. Her first magazine story, “Help Wanted,” was published in the September 1931 issue of Chatelaine. It is difficult to determine how many of her poems, stories and plays were published since only a few of her manuscripts have also been kept in printed form among her papers. She also submitted manuscripts under many pseudonyms including the names Susan Finnie, Margaret Danelaw, Bard Pentecost, E.S.B. Finnie, Peggy Dane, Maple Wilder, and, believe it or not, Flower LeStrange!

J.M. Dent & Sons published a book of her poetry, called Muses of the Modern Day and Other Days, that same year which received excellent reviews. A.M. Stephen wrote in The Vancouver Province that:

Miss Davidson...will challenge comparison with any of the women who are given prominence among Canadian poets....Her best lines and many of her poems ring with sincerity and carry conviction....Strength is seldom an outstanding characteristic of the artistic work of women. Yet, if we are to have poetry expressive of this modern age, it will have to be more than decorative or reminiscent of the modes of a bygone day....She is alive to the fact that this is the age of machinery, of psychology, of intellectual unrest and disillusion. This author can think. Her work is valuable because it mirrors the reactions of a sensitive woman who has faced life shoulder to shoulder with men and who has bravely taken the bitter with the sweet in the struggle for existence. Her poetry reflects life rather than the “the realms of gold” in which the sheltered woman takes refuge from reality.8

E.J. Pratt’s review in The Canadian Student noted that “this little book of poems...is marked by a distinct individuality and by a light lyrical movement which never gives the impression of mere facility ...there is no trace of immaturity in the work. The forms are varied but always under fine control and—what is just as gratifying—the content is rich enough to repay reflection on the part of the reader. One realizes that the writer has something to say as well as to feel, that underneath the moods there is a basis of ideas.”9

Although a critical success, the book enjoyed only limited commercial success. Perhaps that is why True clipped and kept among her papers a poem by Frances Bragan Richman which began, “ They tell me poetry doesn’t pay/And they’re right, I suppose, in a practical way. Since what does it profit a rose to bloom/Like a lamp in summer’s living room?”10

With the loss of her salary from the Vocational Bureau, True had to scramble to supplement the small income made from her writing. Her letterhead from 1932 listed her as doing “Manuscript Criticism, Revision, Research, Statistical Work, Typing, Placement”11 and there is a small advertising card in her files in which she advertised a course for “Current Literature Groups” that she was leading. The same flyer also advertised that she would provide special lectures on topics as varied as, “The Straw Scarecrow and other Dictators, The Matriarchal Tradition, These Crazy Poets, A Trip to China in Novel Company, Women at War” and noted that she would provide “similar Topical Talks for professional and other specialized organizations. Fees according to numbers and purpose.”12 Among some of the groups to whom she spoke were the Lyceum Women’s Art Association, where she criticized modern poetry, and the Lynbrook School Dramatic Club, where she spoke about amateur theatricals, “stressing the possibilities and pitfalls open to beginners.” 13 Many years later, True was asked by a shy student about her public speaking. Clara Thomas wrote that “the reply was one of the most unforgettable pictures of True that she treated us to. “I practise in front of a mirror,” she said. “I’ve practised all over, sometimes in hotel rooms, before a mirror, wearing the hat I’m going to speak in, and my slip.”14

True Davidson, 1923, age 22. Courtesy David Cobden

Another of her schemes was an attempt to work up orders for a book of poems from the shop owners along Bloor Street which they could use both as advertising and as incentives for their customers. Under this enterprising scheme she proposed to publish 1,000 copies of her poems which had been inspired by the scenes along Bloor Street; to sell three hundred of them through bookstores; and to distribute the remaining seven hundred to a selected list of addresses in Rosedale and the Annex or (for an extra fee) to the preferred customers of the sponsoring firms along with their card. All advertisers were to have their name and address also shown at the bottom of the poem they had inspired.15 She got an estimate on the cost of printing the book from the T.H. Best Printing Co. which described it as having “64 pages...28 pages small cuts, quarter bound, cloth back and paper board sides.” She went as far as to have them prepare dummies in October 193316, but she was never able to sign up sufficient subscribers to have it published.

While her money-making activities were a constant struggle, True enjoyed several successes in other areas as she continued her involvement with left-wing organizations and took part in debates and other activities at the university and with the University Women’s Club and the Business and Professional Women’s Club. A review of one of this latter group’s debates noted that “the subject of the debate was: “Resolved, that business women make the best wives.” The affirmative was upheld by Miss Jane McDowall and Miss Helen Lynn, and Miss True Davidson and Miss Mary Dale Muir were on the negative side. The argument proved an amusing one, and the result was lost in the laughter of the audience.”17 At another debate, the University of Toronto Womens’ Union declared that they would prefer to be Agnes MacPhail than film star Mary Pickford.18

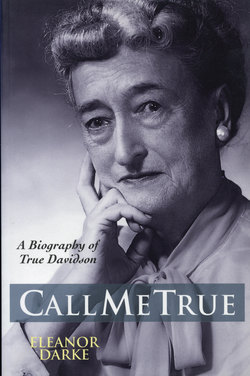

In April 1931, True was awarded a $100 prize from the Women’s Canadian Club for “the best poem written in Canada that year.” Shortly afterwards a collection of her poetry was published which received several glowing reviews and which heralded her work as challenging in “comparison with any of the women who are given prominence among Canadian poets.” Courtesy David Cobden

Her involvement in left-wing organizations likely began from her contacts with the League for Social Reconstruction and the Canadian Forum and was strengthened by her own financial struggles and by the conditions observed while she worked at the Vocational Bureau. One of her earliest activities helped the Toronto Branch of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom set up a book-room.19 The wife of one of True’s professors, Anna N. Sissons, was the corresponding secretary for this organization and it was at her home that True had lunch with J.S. Woodsworth and experienced what she later described as an “old-fashioned religious conversion.” This led her join the C.C.F. in 1934, only two years after it was founded.20 Professor C.B. Sissons, a University of Toronto classicist, was Woodsworth’s cousin and had been the best man at his wedding. In a later interview she repeated that she “was first attracted to socialism by J.S. Woodsworth, the C.C.F. leader...[because of his]...love for people. You could warm your hands in his personality.”21 Woodsworth was about the same age as her father and his dedication, deep sense of calling and ministerial experiences in the western provinces doubtless reminded her strongly of him. Although Woodsworth had considerable influence on politics and on the provision of social services in Canada, he was far from a typical politician. He was driven by ideals rather than the necessities of maintaining political power, although he negotiated many very successful compromises. Once again True had found a sense of calling. As Walter Young wrote in his book, The Anatomy of a party: The National C.C.F. 1932-1961 “... the socialism of the CCF inspired service and sacrifice; it was a faith [its members felt] worth crusading for since it offered everything that was good and opposed all that was bad.22 Woodsworth told a national convention, “In our efforts to win elections we must not yield to the temptations of expediency. Let us stick to our principles, win or lose.”23 Although, like the majority of the party, True later supported the declaration of war against Germany in 1939, it was Woodworth’s principled stand against it that she remembered best and later included in a short poem.

Opponents said to J.S. Woodsworth once

(The noted pacifist), “We must fight fire

With fire,” but, smiling gently, he replied

“Fight fire with water, rage with peace, and hate

With patient understanding and with strong

Persistent loving and with tireless faith....24

Throughout her life True collected odd newspaper clippings and wrote out quotations which appealed to her. Among these are some which reveal aspects of her thoughts and feelings about the party. One of these quotes, attributed by her to Grover Cleveland’s “Annual Message for 1888”, said “The Communism of combined wealth and capital...[is]...not less dangerous than the communism of oppressed poverty and toil.” Another noted that “Socialism inevitable if world wants to avoid Communism” and another, somewhat sadly, that “Those of us who are in earnest must be ready to face antagonism, ostracism.”100

Her experiences in the Depression showed in one of her poems entitled, “Free Enterprise.”

“My little plant,” the manufacturer said

With modest praise, leading his guest by row,

On row of trembling girls, who worked below

The earth-line, in his cellars. Pale as snow

The flowers in their cheeks. That was a bed

Where only livid parasites could grow.

He did not feel the cold. Rotund, well-fed,

He did not know his plant’s deep roots were dead.101

True’s friend, Emily Smith, suspected that True liked the C.C.F. because “the odd parties had an appeal for her...they were not strong the way old political parties were...they didn’t have the cohesiveness... she would have liked stepping in and getting it going...but if you get into a party thats already established [you can’t do that] ...” While True’s support for the C.C.F. slowly waned over the years as many of the social welfare issues she supported were implemented by the other parties and as she became increasingly uncomfortable with the growing importance of labour unions within the party, she remained an active supporter until shortly before the C.C.F. joined with the Canadian Labour Congress to form the New Democratic Party.