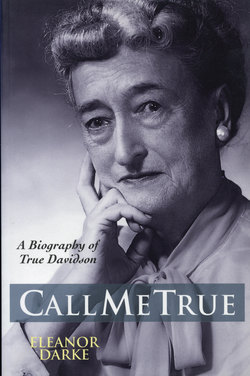

Читать книгу Call Me True - Eleanor Darke - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

A CHILD OF CANADA

FAMILY

Jean Gertrude Davidson was born in 1901 in Hudson,Quebec. She assumed the nickname, True, early and reinforced its use throughout her life, even refusing to acknowledge any other name on occasion4. Although the reference letters from her professors all called her Jean Gertrude5, her listing in Torontoniensis, the University of Toronto yearbook listed her as J.G. “True” Davidson.6 The first letter she received from Bryn Mawr offering her a scholarship addressed her as Miss J.G. Davidson, but subsequent letters were addressed to “True” Davidson, no doubt at her insistence.7 Although she couldn’t have known how useful it would be to her future career, her choice of name was an inspired one. As one of her friends later said, “It was a good name for her... she was smart...a good short political name.”8

Because her father was a Methodist minister, the family moved frequently. By the time True left high school she had moved nine times and had lived in four different provinces. Although it was common for the Methodist clergy to change churches frequently, moves were generally within the same or nearby conferences. Her father appears to have difficulties as a minister, necessitating more frequent, complete changes. Charlotte Maher, who knew True near the end of her life, recalled her saying that her father “sort of got fired from some of his parishes.”

True, herself, chose to regard these moves as a positive thing. As early as 1931, she was quoted as claiming “Canada in general as her home, for, she explained, she had lived in almost every province.”9

True was enormously influenced by her father. She seems to have spent her whole life trying to live up to what she thought he wanted her to be, writing years later that:

...at school I was expected to top my class, and school, and even my province. Every time I met an expectation it became harder to face the next time I failed to do so...But it was not until I was a middleaged woman and my father was dying that I discovered that he had been fiercely proud of me all along, and only wanted me to be all that I was capable of being. Which is very different from being first. And the realization changed my entire life...10

True’s father, John Wilson Davidson, was born at Union, Ontario, on April 29, 1870, one the large family of James Davidson and Jane Hepburn Grant, who was descended from the same ancestor as Ulysses S. Grant. True later described her ancestors as United Empire Loyalists, “the stiff-necked, unreasonable kind.”11 Like another famous woman of her generation, Agnes MacPhail, this family background had a marked influence on her personality. Terry Crowley wrote of the MacPhail’s family that “More than their heritage made [them] hard-working and self-reliant. Life provided few cushions apart from the support of relatives, and they were only to be called upon in the most dire emergency.”12

True’s father, John Wilson Davidson. Reputedly a brilliant scholar, True’s father seemingly lacked the interpersonal skills to be a successful minister. Courtesy David Cobden

John Davidson’s early education was in Union and St. Lambert, Ontario, and at the St. Thomas Collegiate Institute. He graduated in Arts from Victoria College in 1898 and then in Theology in 1900, winning numerous medals and prizes including the oratory prize. He was ordained the same year and immediately married Mary Elfleda Pomeroy, the daughter of a Methodist minister. Their first charge was the mission church at Hudson-on-the-Lake, Quebec, where True was born one year later. The next year they moved to St. Lambert, Quebec for one year; then to Montreal, where True’s sister, Marsh, was born. These charges were followed in quick succession by Ormstown, Quebec (1904-5), Waterloo, Quebec (1905-9), and Delta, Ontario (1909-10). Then, when True was nine years old, they moved west to Vancouver (1913-1915), followed by a move to Regina where the pace of moves finally began to slow. Rev. Davidson served as minister of Wesley Church in Regina, Saskatchewn from 1915-1919; then moved to Rae Street Church, still in Regina, from 1919-22.13

The most open interview True ever gave about herself was to Warren Gerard for The Globe Magazine in 1971. In it she revealed an “extraordinary affection for her parents” and said of her father that:

Well, he was a very brilliant man. The whole family was brilliant. They were of Scottish extraction...[She describes her father as not a worldly success in the church.] I don’t know what happened. I think that perhaps my mother cared too much. Perhaps she was too ambitious for him. Perhaps he was too proud. Perhaps he had difficulty finding his way with people.14

True dedicated her book, The Golden Strings, to her father with a poem which reads in part:

To My Father

Misunderstood and lonely

Almost to the end,

Your courage never faltered,

Your will knew not to bend.

Pity you learned and patience

Beyond all grief or mirth,

And your love was rooted deeply

As a tree in ancient earth

You found a sweet solution

For frustrate human pain,

And your faith was clean and quiet

As grass after rain

She ends the poem with the dedication, “All I have done, my father, Since then, I owe to you.”15

Whatever her father may have lacked in worldly abilities, True believed that he had a true calling and never doubted the sincerity of his faith. Her entire life appears to have been a search for the same depth of faith and for a calling to which she could give the same level of devotion. She told an interviewer that “I have a very clear recollection of church services. My father’s hair became white very early and he did have a very rapt and dedicated look.”16 Although her religious faith was never as easy or uncomplicated as that her parents appear to have had, she credited them for having shared their faith with her and wrote that “My parents and my church may not have been, as they seemed to me, the best parents and best church in the world, but they gave me the God that I shall never quite lose. The best Christmas gift for any child.”17

Charlotte Maher said that she always pictured True’s father from her description as having been “a dour type who always dressed publicly in a tight collar...” All sources seem to indicate that he was an austere, very correct, highly intelligent, very principled man with a deep sense of religious calling, a scholar whose ascetic, reasoned faith wasn’t easily conveyable to ordinary, compromising people.

In 1930, True wrote a short story which may have illustrated her belief that her father had sacrificed a successful scholarly career to work as a country minister. In the story, a country minister has written a novel and is considering submitting it for publication. His wife encourages him by reminding him of the kind comments made by his university professors about his writing. However the manuscript is unpublishable and the story ends with him having received a rejection letter from the publisher.

He turned to go, moving slowly and carefully like one in a dream. Five years’ work gone for nothing—five years, and failure at the end! When they had all told him he could write!...He had been so sure he could write. The college magazine—all his professors—what had happened to him? Perhaps, after all, he was not the old Samson—not the old Samson, but Samson shorn, blinded and among his enemies. Perhaps, after all, more relentless than captivity or death, the years did something to a man. The years—the Philistine years.18

The same story portrayed a devotion between the minister and his wife that I would like to think was enjoyed by True’s parents. “They looked at each other, and in their eyes again for a moment flared the gleam that age...cannot dim, and that is sweeter than many apple-blossoms.”19

True’s attachment to her mother wasn’t as intense as the unity she felt with her father, although she respected her mother, saying of her that: “They [my parents] had a passion for truth and scholarship, and my mother had a passion for the arts as well. My mother painted. Our home was full of paintings when I was young. She was a musician. She was talented dramatically. She was the life of the church cultural programme.”20

True’s mother, Mary Elfleda [Pomeroy] Davidson. True loved her mother and cared for her for many years but was never as close to her as she was to her father. Courtesy David Cobden

It appears that True’s mother was devoted to her husband, but frustrated at his lack of success; a frustration likely deepened by comparison with her father’s prominence within the church and by the fact that her success was totally dependent on that of her husband. While her father, Rev. John C. Pomeroy, also had been a scholar he had been a highly successful minister as well, holding several of the most important circuits and stations in the Methodist Church. He was described as being “highly gifted and...warm, impassioned and convincing...He possessed the most pleasing personality, his disposition being most kindly. It was easy for him to make friends. He was the life of any circle in which he found himself.”21

True and her sister, Marsh. Even then True preferred to read a book! Courtesy Michael Cobden

Both of True’s parents were very interested in the youth of the church. Their activities in this regard again illustrate the differences in their personalities. While True’s father did committee work as Secretary of the Religious Education Committee of the Saskatchewan Conference, his wife was active in the creation of the Y.W.C.A. and in helping to organize the new Canadian Girls in Training (C.G.I.T.) group in their area.

The relationship between True and her sister, Marsh, was the most complex of all. True’s nephew, Michael Cobden, later described it to Charlotte Maher, as “the original love-hate relationship.” To me he said that his mother had been “the pretty one, the popular one” and that he had been astonished by the depth of resentment and rivalry that True later had expressed to him about his mother.22 Marsh seems to have inherited all of their mother’s social abilities and ease with people. The rivalry was primarily on True’s side, caused by her insecurity regarding Marsh’s popularity. She saw her sister as a rival for their parents’ love. Charlotte Maher told me that she always felt that True “would have liked to have been like Marsh. I think she was envious of Marsh. I think she would have liked to have been little, and feminine and pretty.” Doris Tucker, who was Clerk of East York while True was Mayor and who shared many conversations with her, agreed that True had expressed resentment concerning her sister, feeling that she had been stuck with all the responsibility for the parents when they became old and that Marsh had an easier time in life than True. Doris particularly remembered that “her sister didn’t go through what she went through to go to school. They were a little better off when the sister came along. She told me that.”23 True likely was referring here to the fact that she had to work for a few years between taking her B.A. and her Masters Degree, since the age difference between the two girls during their undergraduate years wasn’t great enough to have made any substantive difference in the family’s income.

True and her sister Marsh as children. Courtesy David Cob den

Things may have been better by the time Marsh was doing her graduate work, but the family never had money for luxuries. Columnist John Downing was only one of many who commented on her childhood poverty when he wrote that “True could be tight with [the public]...dollar, due to her childhood in the genteel poverty of a Methodist manse.”24 In a short story she published in 1930 True conveyed very effectively the discomfort and general meanness of her “genteel poverty” in a passage describing the chair in which her minister protagonist sat. “The chair was not a comfortable one. Its back disdained the easy luxury of curves, and rose with puritan rigidity at a direct perpendicular just to the point where it could prod the spine with the maximum of discomfort. The seat was too shallow, the arms, too high and too wide apart for convenience, were not wide enough or sufficiently remote to be ignored. In a word, it was just such a chair as is always found in village parsonages, in cherry finish, to accompany a desk in golden oak.”25 Doris Tucker remembered True mentioning that she had had only one dress when she first went to Victoria College.

Perhaps the best description of True’s almost hysterical rivalry towards her sister came through in a later interview when in describing how prayer helped calm her, she said, “I can remember as a child I was high strung and tense. I can remember dropping to my knees beside a mattress in a playroom...I couldn’t have been more than seven and I asked God to please help me find my diary or my sister would get it. Not that she could have read it anyway.”26 [Marsh would have been only 5 years old at the time.]

It also shows something of the emotionalism of their lives. Isolated by their father’s position and by frequent moves, True found making deep friendships difficult. The family was also intellectually and educationally separated from most of the parishioners in their country postings. Clara Thomas recalled that True and her friend, Edith Fowke “was born in Lumsden, Saskatchewan...and True’s father was a minister there for awhile. When Edith was young she got to know True through the family because they had a lot of books and Edith was, from birth, a reader and during the Depression, of course, there were few books around and the Davidsons let her just walk in and out of their house and borrow their books at will.”27 True also described their library and that “Nobody tried to hold me from anything in my father’s library. I read all of Shakespeare before I was nine. It was in a great big India paper edition, illustrated and unexpurgated.”28 Their isolation drove the family to seek everything from each other, intensifying all of their relationships.

True’s early emotional loneliness formed a pattern which continued for the rest of her life. Many who knew her commented on how, although a very social person, True had few close friends and that they felt she was a lonely woman. Doris Tucker remembered a “chap on the school board [who] said ‘You’re her friend for so long, then all of a sudden she gives you the boot...You’ll find that she has a friend for awhile and then she’ll drop him.’ Myself, I used to say ‘that’s her Achilles heel. As soon as people get too close to her she pushes them away. You see. There’s something about her background. She just doesn’t trust people.’” Her nephew, David Cobden, remembered that she didn’t really warm up to him until almost the end of her life although his wife said that, by then, True was extremely fond of him.29 Charlotte Maher said that “when the purpose [for which she needed someone] ceased to be served she dropped them...the closest she was to anyone was to Emily Smith” but Emily said that True seldom shared her personal feelings or background with her.30 Charlotte qualified her comment, however, by noting that “I really didn’t care very much because it was all so exciting.” [Being with True and meeting people True knew.]

Marsh was every bit as academically brilliant as True. Like her sister, she earned an M.A. from Victoria College, in her case, in Psychology. She worked at an Ontario mental health clinic, then travelled to Europe to study for a post-graduate degree with Dr. Alfred Adler in Vienna and at the University of London where she published two articles in the British Journal of Medical Psychology.31 She was a member of the founding staff at Summerhill, the famous British alternative school. Marsh married in the late 1930s, moved to South Africa and had two sons.

She returned to Canada, with the two boys, in 1946 and stayed with True in Streetsville for a year. This was soon after their mother’s death and may have been an attempt by Marsh to provide True with some of the support that she needed then.32 While her children were still young and at boarding school, Marsh was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Her decision to leave her husband and children and come home to Canada to die may be the best possible illustration of the depth of attachment between the sisters, despite True’s underlying rivalry. Marsh died soon after her arrival in Canada and was buried beside her parents. Her decision to return to Canada at that time was something her children never understood other than to say that “they [the Davidsons] were an unusual family.”33

CHILDHOOD AND SCHOOL DAYS

True told few stories of her early years and even fewer of the people she had met then. Most of her childhood stories related to the places where she had lived and demonstrated her strong, poetic attachment to Canada’s geography and history and her love of nature. She told one reporter that she had been born in a village near Montreal “on the shores of that Lake of Two Mountains that knew the steps of Champlain.”34 She recalled her father taking her to hear Sir Wilfrid Laurier talk when she was nine years old:

I might as well say it, I was a precocious child, and when my younger sister was sleeping in my father’s lap, there I was listening to that courtly, white-haired, dignified man—and thinking even then that what I wanted to be was a...politician.35

A common comment by those who knew True is that she rarely discussed her past, her family or other people. Her activities were constantly focussed on what she was doing now and her conversations were almost always about ideas. Several noted that she seemed to prefer talking to men, perhaps because she felt that their discussions were more likely to be of this sort. It was fascinating to note in Doris Pennington’s book about Agnes MacPhail that Agnes had the same preferences.

In a CBC tape [Agnes MacPhail’s sister] said that at parties it was the custom for women to visit in one room, men in another, while the young people gathered in a third. Agnes was generally to be found with the men, “discussing such things as farm prices.” Lilly would go after her and say, “Why don’t you come in with the rest of us? We’re playing cards.” But Agnes would generally stay with the men.36

True’s deepest attachments from her teenaged years were to the open lands of the prairies. One of her poems, quoted in part below, expressed her love of their natural beauty and the sense of emotional refreshment they gave her.

Land of Greatness

I used to walk on the prairies,

In the tangled, wild-flower spring

With the wet wind sweet on my forehead

And the migrant birds a-wing.

And life was a wonderful thing.

................................

I must go back to the prairies,

For, whatever change I meet,

I must sense again the vastness Of those miles of cattle and wheat,

Where earth and heaven meet.37

True began writing poetry at an early age and later claimed that the idea for her best poem was conceived when she was fifteen years old.38 She excelled at school, matriculating from South Vancouver High School in 1915, then graduating from Regina Collegiate Institute.39 One of her early resumes included information about her first summer job—working in a shoe store and doing playground work—followed by three summers of clerical work during 1917-19 for the Government of Saskatchewn, one year in the Treasury Department and two in the Education Department. Her final summer, between receiving her B.A. and entering Normal School (teacher’s college), she worked for the Regina Public Library.40

True’s mother had been instrumental in the formation of a C.G.I.T. group in Lumsden, Saskatchewan and True became one of its most active leaders. Sixty years later she recalled the day that she made her pledge as a Canadian Girl in Training in Saskatchewan.

At the end of a conference we sang an old-fashioned song, “Beulah Land.” I said, “For three days we have been living on the mountains, underneath a cloudless sky. Now we are parting and going down into the valleys. There will be clouds and sometimes we shall feel alone. But we shall not be alone and we shall remember the sun is still there even when we cannot see it. And we shall keep our pledge.”41

Although its influence has decreased greatly in recent years, the C.G.I.T. provided leadership for many young women. According to The Canadian Encyclopedia, it “was established in 1915 by the Y.W.C.A. and the major Protestant denominations to promote the Christian education of girls aged 12 to 17. Based on the small group whose members planned activities under the leadership of adult women, the program reflected the influence on Canadian Protestantism of progressive education, historical criticism of the Bible, the social gospel and Canadian nationalism.”42 The pledge, or purpose, that is still said aloud at meetings by both members and leaders had a large influence on True and reads:

As a Canadian Girl in Training

Under the leadership of Jesus

It is my purpose to

Cherish health,

Seek truth,

Know God

Serve others

And thus, with His help,

Become the girl God would have me be.43

UNIVERSITY DAYS

A little more can be discovered about True’s university days. She later recalled that: “My father sent me to Victoria, which is the first line of the college song. An awful song. My father sent me to Victoria and resolved that I should be a man. And so I settled down in the quiet college town on the old Ontario strand. That was when Victoria was at Cobourg.”44 She began her studies at Victoria in 1917 when she was only sixteen years old. A classmate recalled many years later that “she was the youngest and smartest student in the freshman class.”45 Clara Thomas knew several women who graduated from Victoria College around the same time as True and said that they all seemed imbued with the same drive, dedication and strong sense of ethics, whatever field they later entered. They were a small, select group. Women composed only a handful of Victoria’s graduates at that time. They were also the first generation of female graduates empowered by womens’ acquisition of the right to vote.

Once again, True excelled academically and was involved intensely in all the activities that the university had to offer. Margaret Addison, the Dean of Women, wrote in her letter of reference in 1922 that: “Miss Davidson has unusual ability, did very well in her college course, especially in English, in which she is exceptionally gifted. She has much originality and initiative; she is energetic, interested in games and in dramatics, in which she took a prominent part while at College.”46 The College Registrar and Associate Professor of English, C. E. Augery, noted in her reference letter that: “I can confidently say that she is one of the best students I have ever had....She has exceptional ability in debating and as an essayist and writer of verse. She is thoughtful and courageous and well qualified to exert a strong influence in any school fortunate enough to secure her services.”47

Brandon Collegiate Institute, Manitoba. True taught English here in 1923 to help raise the money needed to return to Victoria University to take her Masters Degree. Courtesy David Cobden

In addition to topping her classes academically, True was active in a myriad of committees including the 4th Year Executive and the Women’s Undergraduate Association and was President of the Women’s Literary Social Executive. The information below her photograph in the 1921 yearbook read:

J.G. (“True”) Davidson

“Laughter, Love and Tears”

Weaknesses —Class, Dramatic, “Y”, Presidency of Literature

Strong Points—consuming chocolate bars, composing rhythmical nonsense

Glory—Debates, oration contests

Shame—Last month’s essay unwritten

Extraordinary—Passion, vitality, energy, nerve

Ordinary—Her “bete noir”

Past—Ubiquitous, various, rainbow-hued

Present—Flaming, intense, moody, alive

Future—Inky black or rosy gold.48

There were very few men at university in her first years there. As she later said, “We came in the fall of 1917 and the war wasn’t over until the next year. In our third year there was a flood of returned men. The whole college changed and it was quite an experience. A sort of traumatic experience.”49 It is this reminder of her age during World War I that eliminates the persistent rumour that True never married because the man she loved had been killed in battle. She was 13 when the war began and only 17 when it ended. It is highly unlikely that she would have formed such a lifealtering attachment at that young age. What is perhaps more interesting is the need so many people have felt to invent a romantic reason for her not marrying.

This photograph shows True, aged 16, wearing her C.G.I.T. uniform in 1917. Courtesy David Cobden

In many ways, True was Victorian in her attitudes. She was too Victorian to discuss the details of any romances and somewhat surprised that anyone would have the bad taste to ask, but occasionally, in a naughty mood, she would acknowledge that she had her opportunities. Clara Thomas remembered her class “discussing Sarah Jeannette Duncan’s The Imperialist. “To the ears of the young in 1975 the dialogue sounds pretty stilted and one young man remarked that he simply couldn’t believe that young people ever talked as Duncan wrote them.”

“Indeed we did,” said True. “When I first went to Victoria, we weren’t allowed to have dances. We had Conversats, and we marched around the Great Hall to music. Then the veterans began to come back after the war, and they used to walk us right out of the room and upstairs to dark classrooms. And soon, we were allowed to have dances in the Great Hall—better to have dances in the light than students upstairs in the dark!”50

Agnes MacPhail recalled a similar entertainment at her high school where, once a year, “the young people walked around the auditorium in couples. When the music ended, the boy escorted the girl back to her seat and chose another partner for the next “promenade.” At the last promenade the partners enjoyed a dish of ice cream together.”51

True later told an interviewer that she had her romances, but that they were pretty tame.

I was pretty innocent and unsophisticated and I thought if I were attracted to a man I must want to marry him and when ...I found out about what went on between young men and young women...I think it turned me against the whole thing. If I wanted a man to kiss me I thought I ought to want to marry him and when I came back to Toronto in the Roaring Twenties, when people were lying down in swathes on the floor in darkened rooms and drinking themselves into stupors, it seemed to me all so sort of messy. I guess I’m a romantic. Any man I could talk to I would talk to. The only time we exchanged passes was if we couldn’t think of anything to talk about. The result was that the men I had little affairs with, I don’t think would have been happy with me any more than I would have been happy with them. I would have driven them crazy. They had a narrow escape. I think they realized they were well out of it. This is a sad fact of life. Women want men who are stronger than themselves, men they can look up to. I wouldn’t have wanted to marry if I couldn’t have made the man’s interests mine... I grew up thinking I would find a man who was so strong and great and wonderful that I would be glad to spend the rest of my life looking after him and my children. And I just never found any such person.52

True learned to turn such questions into a joke. Many years later she told a student who asked why she never married that “....in my twenties I realized that I talked too much for any man, and I certainly didn’t plan to give up talking.”53 Emily Smith told me that “with the right person she would have had a very much happier time. She didn’t have that support system. She talked to me a lot but it wasn’t like having a family.”

Although True never found the person to whom she could give the complete dedication she felt essential for marriage, the thought that such a person might come along did not die right after university. Among her clippings from the early 1930s was one headed “Why I Asked Her to Marry Me. Ten Men Give Their Reasons.”54

In 1922 True graduated from the Regina Normal School with her teaching certificate and immediately began work as a teacher/principal in Strasbourg, Saskatchewan. There she “taught English, History, Science and Art in all collegiate grades and was principal of a 3-room High School and a 5-room Public School.”55 What a killing task! She also won a magazine prize for the “Best CANADA Poem.”56

The following year she moved to Brandon, Manitoba where she taught English at Brandon Collegiate, earning the money she needed to return to Victoria College to take her M.A. Once again, she excelled academically. Upon graduation she was offered a $350 scholarship from Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania to do post-graduate work there. She evidently declined on financial grounds, because they then wrote back with the offer of another half-scholarship,57 but she was still unable to accept the offer.

It must have been a considerable disappointment to her to have to decline such an honour. Doris Tucker wondered whether it was a matter of finances, noting that “Bryn Mawr was a pretty toney place. She probably couldn’t afford the clothes.” Emily Smith felt that True wouldn’t have liked going to teach in the United States because she was so attached to Canada. Clara Thomas suspects that True recognized the impossibility of a successful academic career for a woman in those days and knew that she should a better chance in business. It also may have been a matter of family obligations. Her father’s eyesight began to fail him in 1925 and he returned to Ontario.58 A later successful operation for cataract, then a very difficult medical procedure, restored his sight and he returned to work for a couple of years in 1938, but until then her parents were living in Toronto and needed her help. True returned to teaching, obtaining a post at Havergal Ladies’ Academy where she taught History until 1926. That year, she began her next career, joining the staff at J.M. Dent and Sons Limited, Publishers, as the first female publishing sales representative in Canada.