Читать книгу Life of Geisha - Eleanor Underwood - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

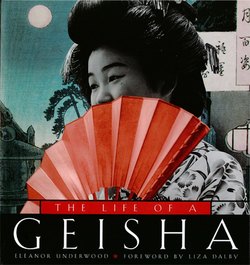

ОглавлениеFOREWORD

I was twenty-five when my "older sister" Ichiume first brushed the geisha's cold white makeup on my face. She was twenty-one. In the geisha world of Kyoto she was still my senior since she had graduated from the status of maiko to that of full-fledged geiko the year before. I, of course, had never been a maiko. Ichiume had taken on the task of showing this American graduate student the inside perspective of a geiko (the Kyoto dialect term for geisha) behind the history, the statistics, and the interviews I had been collecting. Some customers were surprised to find their sake cup filled by an American geisha; and some didn't even notice until the other geisha began to giggle.

I made no secret of the reason behind my transformation into Ichiume's younger sister Ichigiku of Pontocho-I was trying to obtain a deeper understanding of the profession of geisha in order to write my Ph.D. thesis in cultural anthropology. The suggestion that I put on kimono and take my shamisen to the teahouses came from the geisha themselves. After I had gotten to know them and they me, they seemed to think I might be able to tell their side of the story-for geisha definitely feel they are misunderstood in the West.

The word "geisha" conjures up a mythically exotic creature in the Western imagination. Fantasy, wishful thinking, and plain misconceptions have been bound together with threads of fact, so that in English to say "geisha" summons a vision of a servile beauty who dotes upon her master's whim, satisfying every desire. Her personality he need not bother about, and she will obligingly melt away like Madame Butterfly rather than disturb him. This fantasy is hard to project on a real woman, but settles quite easily on a mythic one.

Geisha have the odd distinction of being both legendary and real, and this book helps clarify those differences. Myth by nature is monolithic, transcending history and individuals, whereas the reality is a variety of geisha communities in different areas of Japan, status hierarchies among communities in the same city, and of course differences among individual geisha.

This is not to say that geisha are not exotic. These women are more mysterious than they themselves imagine-in Japan as well as outside it, albeit for different reasons. Westerners have a notion that geisha must be experts in the art of subservience in a country like Japan where even ordinary women are supposed to put men first. We infer that the art of pleasing men would mean being even more servile. I myself accepted this myth before I learned better as Ichigiku. To my surprise, I found that the social give and take between geisha and customers in the teahouses of Kyoto was quite comfortable to an American-bred geisha. One must not confuse the general cultural norms of Japanese politeness with subservience. Geisha are among the most outspoken Japanese women I know. Of course they are socially skillful-like a good hostess in America they don't say things that would embarrass a guest. But it became clear to me that Japanese men do not consort with geisha because they crave more subservience. They crave interesting conversation and lively personalities.

We do not have an institution comparable to geisha in modern Western societies. Geisha do not marry, but they often have children. They live in organized professional communities of women. They have affairs with married men, and can form other liaisons at their own discretion. They derive their livelihood from singing, dancing, and chatting with men at banquets. They devote their time to learning and performing traditional forms of music and dance. And they always dress in kimono, but not always the form.al costume. In various ways, then, geisha may be like mistresses, waitresses, hostesses, dancers, or performers. If she's not in full dress, can you tell she's a geisha? If you know what to look for, yes.

As Japanese women, the most important social fact about geisha is that they are not wives. These are mutually exclusive categories because of the way women's roles have been traditionally defined in Japan. Wives have always controlled the private sphere of home and children; the profession of geisha, for all its exclusivity, came into existence in a space separate both from the private world of the home and the public one of business. This was the arena where men could socialize. Geisha are by no means the only women who serve this function-they are outnumbered 1000 to 1 by bar hostesses in modern Japan- but this is still one of the two raisons d'etre of their profession. This is how they differ from wives. What sets them apart from the other women in the entertainment industry is, of course, their gei, their devotion to traditional arts.

It's true that their world has undergone many changes- it had to in order to survive. Until the 1920's, when they began to look old-fashioned next to the modern cafe and dancehall girls, geisha had been society's fashion vanguard. But in the face of modernization and westernization, geisha managed to twist the meaning of their profession in the opposite direction and transform themselves from fashion innovators into curators of tradition. Leaving Western dress to the bar hostesses, geisha turned kimono into their uniform. In this way they found their niche within modern Japan. The experience of oppressed indentureship of Arthur Golden's character Sayuri in his book Memoirs of a Geisha no longer occurs, nor does the custom of ritual defloration of a maiko, a privilege bestowed on the highest bidder. Yet older geisha still tell such tales of their youth, along with the strict discipline they endured at the hands of their dance and shamisen teachers.

"You couldn't do that today," said my geisha mother, "the maiko would quit." Arthur Golden accomplished a remarkable feat of imagination when he put himself inside the mind of a geisha and went on to create a compelling personality through the unfolding of events in her larger-than-life saga. Yet in this, Sayuri's story rings true because geisha are still, in fact, larger than life.

Liza Dalby

May 1999