Читать книгу Life of Geisha - Eleanor Underwood - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

A [geisha is a] girl exquisitely refined in all her ways; her costume a chef-d'oeuvre of decorative art; her looks demure yet arch; her manners restful and self-contained, yet sunny and winsome; her movements gentle and unobtrusive, but musically graceful; her conversation a piquant mixture of feminine inconsequence and sparkling repartee; her list of light accomplishments inexhaustible; her subjective modesty a model, and her objective complacency unmeasured.

-Captain Frank Brinkley, at the turn of the century Geisha, along with Mt. Fuji and cherry blossoms, have been symbols of Japan to foreigners ever since Japan opened to the West in the 1850s. Who are geisha? We often hear that true geisha (pronounced gay-sha) are not prostitutes- geisha means "arts person"- but instead are highly trained entertainers. Traditionally their appeal is based on a highly refined eroticism, but the geisha's sexual favors are not directly for sale and are very difficult to attain. In truth, the answer to the question "who are geisha?" differs both geographically and historically within Japan.

The Western fascination with geisha can be seen in many forms. The 1906 opera Madame Butterfly by Puccini, though not actually about a geisha, probably did the most to create the stereotype of the fragile Oriental beauty whom the Westerner loves and then leaves behind. When the post-World War II era brought a renewed fascination with Japan, Shirley MacLaine played a geisha in the 1962 film My Geisha. And even Madonna has taken to dressing like a geisha, in her noted post-modern way.

The sacred Mount Fuji was celebrated in the nineteenth century as a symbol of Japan, as seen in this 1830s woodcut print by Hokusai.

The Japanese themselves have done their part in promoting geisha as symbols of Japan to the rest of the world-geisha have decorated posters advertising Japan ever since Japanese travel posters were first printed. Posters for the first geisha dance spectaculars were written in English as well as in Japanese. Today, many Japanese would concur that geisha represent traditional Japanese feminine virtues, despite the fact that very few Japanese have actually had any personal contact with geisha, since geisha parties are prohibitively expensive.

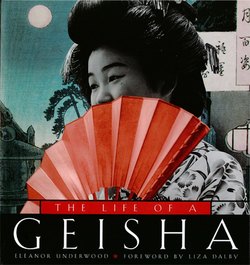

Arthur Golden's fictional Memoirs of a Geisha goes beyond these and other geisha stereotypes and in doing so, brilliantly reveals the fascinating world of a twentieth-century geisha. The book tells the story of a girl named Chiyo who becomes the well- known geisha "Sayuri" in Kyoto's high-class geisha district of Gion, taking us through Chiyo's life from a poor fishing-village girl in the 1920s to her final days as the esteemed mistress of a wealthy patron. In its myriad of details and atmospheric color, Golden's book vividly portrays a little known subculture of Japan in the years before and after World War II. It is a convincing portrait of Sayuri's heroic survival: from her early hardships, through adolescent rivalries, to final happiness. With vibrant ukiyo-e prints, period photographs, evocative poetry, geisha songs, and text, The Life if a Geisha explores and expands upon the world of the geisha that has long intrigued observers around the world.

Early in the century foreign visitors to Japan could buy postcards featuring geisha and cherry blossoms, both already symbolic of Japan.

Two maiko display back and side views of their gorgeous attire as they look out toward this Kyoto covered bridge.

Like the character of Sayuri, many who became geisha were born in poor agricultural or fishing villages before being sold to oki-ya houses.

A maiko, framed by the door of a teahouse balcony, gazes out on a pagoda against the Kyoto mountains.

Children play on the beach of a fishing village as little Chiyo did, while their mothers scrub the baskets used to dry fish in the sun.

Two maiko, holding their kimono up with their left hands, chat on the street of one of the Kyoto hanamachi (geisha quarters).

In this ukiyo-e print from the 1850s, Hiroshige depicts travelers on one of Japan's early highways, with Mt. Fuji in the distance.

A young beauty in casual kimono holds her puppy snugly in a piece of cloth in this turn-of-the-century photo.

Sumo wrestlers clap and stamp in a circle for a ceremonious start to the day's bout.

Two young charmers share a large rain parasol as they stroll together under a willow.

Geisha peer through the snow in front of the shrine of Gion in Kyoto in this mid nineteenth-century print by Hiroshige.

The eleventh-century The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu epitomized the sensitive ideal of Japanese romance that inspired Edo-period fantasies enacted in the pleasure quarters. This 1896 image of Ukifune is based on a picture by Mitsunoki.