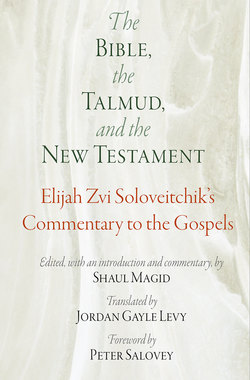

Читать книгу The Bible, the Talmud, and the New Testament - Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik’s maternal grandfather was Hayyim Volozhin, the disciple of the Vilna Gaon, who founded the great yeshiva in Volozhin. And his brother, Isaac Zev Soloveitchik, was the father of a rabbinical dynasty. That dynasty began with Isaac Zev’s son, Joseph Dov Soloveitchik (the Beit ha-Levi), who was the father of Hayyim Soloveitchik (the Brisker Rav), who was the father of the next Isaac Zev Soloveitchik (Velvele Brisker) and Moses Soloveitchik (a distinguished rabbi who emigrated from Volozhin to Khislavishi to Warsaw to New York, where he taught at Yeshiva University), who was the father of Joseph Dov Baer Soloveitchik (the Rav), late of Boston and New York, and one of the founding figures of what we now think of as Modern Orthodox Judaism. So that’s the side of the family that I think of as the “Volozhin-Brisk [Brest Litovsk] connection.”

But if we track Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik’s direct descendants (rather than his brother’s), we come first to his son, Simcha Soloveitchik, who emigrated to Jerusalem, where he was known as the Londoner. His son was Zalman Yosef Soloveitchik (after whom my brother is named), who lived in Jerusalem, where he was an apothecary and community leader. His son was my grandfather, Yitzchak Leib (Louis) Soloveitchik, who emigrated from Jerusalem to New York, where he changed the family name to Salovey. And his son, my father, Ronald Salovey, was a retired professor of chemical engineering at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles who passed away in June 2018. And I am Ron and Elaine Salovey’s eldest child. Perhaps we should call this part of the family the “Jerusalem connection.”

Writing about one’s lineage (yichis, in Yiddish) can sometimes come across as bragging, and there is an old saying in Yiddish that translates, roughly, as “Yichis is like a potato; the best part is in the ground.” But in case you find all this mildly intriguing rather than absolutely confusing, the bottom line is that Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik is my great-great-great-grandfather, and he was the brother of the Rav’s great-great-grandfather.

I take you through the primary boughs of my family tree, I must admit, with some pride. And growing up, I heard many stories of the famous rabbunim in my family, as well as about life in the Geula neighborhood of Jerusalem, immigration to the United States (and the changing of our name, with its odd spelling but including in it my grandfather’s desire to preserve “love”), as well as about various family connections from Hayyim Volozhin down to the Rav. But the one person I never heard about growing up was Elijah Zvi, whose writings are the subject of this fascinating book. Perhaps this was because he was an obscure figure, or perhaps it was because his direct decedents did not become rabbunim like his brother’s. But since learning about his book on the Gospels, I have always wondered if, in reality, the family knew about his writings, and chose to hide him from view.

I am sure that some in my family cringed when they read the title of Shaul Magid’s article about Elijah Zvi in Tablet, “The Soloveitchik Who Loved Jesus.” I did not, although I am not sure whether Elijah Zvi actually “loved Jesus” or had other motives for writing about Christian thought. I like to believe that he was a brave soul—blind and seeking treatment in London at the end of his life—who wanted to provide a basis for Christians and Jews to respect each other, and he did that from the perspective of an observant Jew aware at all times that he was the grandson of Hayyim Volozhin. I like to believe that he chose Matthew as a focus (perhaps his first focus) in part because Matthew’s Jewish origins are revealed through his writings. I like to believe that Elijah Zvi was, quite simply, ahead of his times (at least among nineteenth-century Soloveitchiks) and that he wanted to enable what we now call on campus a “difficult dialogue.”

Thank you, Jordan Levy, for the translations of my great-great-great-grandfather’s work, and thank you, Shaul, for authoring this thoughtful and respectful—and intriguing—study of an overlooked thinker from a notable rabbinical family. His interests differed so obviously from those of his forebears and nephews, but he models for my generation of the family the significance of independent thinking (even in the context of religious orthodoxy) and the importance of seeking to understand the “other.”

Peter Salovey

President of the University

Chris Argyris Professor of Psychology

Yale University