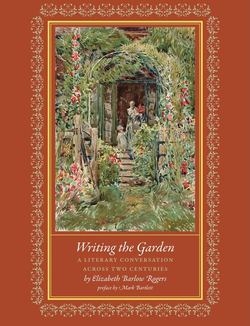

Читать книгу Writing the Garden - Elizabeth Barlow Rogers - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Louise Beebe Wilder

ОглавлениеElizabeth von Arnim’s American contemporary Louise Beebe Wilder (1878–1938) brought the style of rapturously Romantic garden writing to an audience with different growing conditions from those of Germany or England. Unlike “German Elizabeth,” Wilder was anything but a novice gardener. She wrote nine garden books in all and also served as the editor of the journal of the Federated Garden Clubs of New York. Her passionate enthusiasm, vast knowledge of plants, and the verve with which she describes their aesthetic and sensory characteristics as well as their growth habits and climatic suitability have kept most of her books in print over the years. These include My Garden (1916), Colour in My Garden (1918), Adventures in My Garden and Rock Garden (1926), Pleasures & Problems of a Rock Garden (1928), The Fragrant Path: A Book About Sweet Scented Flowers and Leaves (1932), and Adventures with Hardy Bulbs (1936).

Wilder was extremely widely read and could summon as authorities many authors whose works touched on botany, horticulture, or the garden. She frequently consulted the herbalists John Gerard, who wrote the Great Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes (1597), and John Evelyn, the author of Kalendarium Hortense (1664). Pliny, Shakespeare, Bacon, Montaigne, Horace Walpole, and even the prophet Muhammad could be counted on to embellish her words, and she constantly calls on Gertrude Jekyll as well as numerous other members of the intergenerational coterie of fellow garden writers to reinforce her opinions and advice.

My first edition of Colour in My Garden is a beautiful book with twenty-four color plates of Balderbrae—Wilder’s garden in Pomona, New York—painted by Anna Winegar over the course of a single year. Looking at them, I sense within the more formal design structure of Balderbrae the same kind of casual luxuriance that Hassam captured in his paintings of Celia Thaxter’s garden. Wilder’s vivid descriptions of the garden and its plants, however, make illustrations superfluous. To sample her evocative prose, you can read what she has to say about poppies:

The crepe-petalled Iceland poppy (Papaver nudicaule) that sows itself in my garden, springing up in the most unlikely nooks and crevices, has much of the airy charm of the annual sorts and decks itself in the loveliest colours: apricot and orange, buff, scarlet and white. I had from an English seedman this year a kind not too whimsically named Pearls of Dawn, for a rosy glow underlies the soft buffs and creams of its fragile petals.

She then contrasts its beauty with that of the Spanish poppy (P. rupifragum):

It has all the whimsical appeal of its delicately bold race and hoists its little snatches of gay colour on stems as thin as wire. But there is nothing frail about the solid tuft of leaves or the mighty tap root that, when you essay to get it out of the ground intact, seems to reach to China. This plant, too, is as hardy as iron and unmindful of drought as it continues to send aloft its colour until frozen to inactivity.

“Oriental Poppies and Valerian, May 28th.” Colour in My Garden by Louise Beebe Wilder, 1927 edition.

Behind this brilliant group are strong clumps of Gypsophila paniculata which, by the time the Poppies are ready for a rather disorderly retreat underground and the yellowing stalks of the Valerian are cut down, has spread a rejuvenating web of wiry branches and delicate gray-green foliage above their heads and rescued the border from dire forlornity.

Although she may sound as rhapsodic as Celia Thaxter or Alice Morse Earle when she is extolling the beauty of poppies, the similarity stops there. Wilder’s garden was more than a colorful mélange of summer annuals jumbled together like Thaxter’s. Balderbrae was carefully planned according to the picturesque effects derived from various combinations of plant color and form. In addition, Wilder’s considerable botanical expertise extended over a vast range of plants. As proof, Colour in My Garden contains sixty pages devoted to two appendices. The first contains the Latin and common names of thousands of plants in a list that goes from Ambronia umbellate (sand verbena) to Zinnia (youth-and-old-age). The second is a chart for periods of flowering, which Wilder has arranged according to plant color—a still useful aid to those interested in creating harmonious, seasonal garden pictures. Since the blooming dates are derived from the flowers in her own garden, she advises that “an allowance of a week should be made for each hundred miles north and south of the latitude of New York.”

In The Fragrant Path Wilder makes the discerning nose the organ of garden pleasure. With the same botanical expertise as that displayed in Colour in My Garden, she follows each chapter with an annotated list of plants containing descriptions of their appearance, growth characteristics, and, often, the precise smells attributed to each. In addition, we learn this interesting fact: “For the most part fragrant flowers are light in colour or white. Brilliant flowers are seldom scented, though now and again there is an exception to prove the rule.”

Along with such chapters as “Pleasures of the Nose,” “The Sweets of May,” “Summer and Autumn Scents,” “Sweet Scented Flowers in the Rock Garden,” and “Scents of Orchard and Berry Patch,” Wilder includes one on “Plants of Evil Odour.” With forthright candor it begins:

Stink is a robust old-fashioned word once in good social standing but having no character in polite society to-day. Our forefathers used it freely to characterize anything which appealed to them as of an unsavoury nature, whether a disagreeable experience, a damaged reputation, or a stench. That it was frequently applied to plants and with good reason we have only to open such books as ‘A Dictionary of English Plant Names’ to be assured. Therein we find a surprisingly long list of plants whose descriptive title in the vernacular was ‘stink’ or ‘stinking,’ and there are many whose unhappy secret is advertised by the Latin specific terminations foetidus, bad smelling; graveolens, heavy scented; hircine, goatlike odour, and the like.

She knew, probably from reading his famous Diary, that John Evelyn “did not like the smell of Box and referred more than once to the ‘unagreeableness of its smell.’ ” She tells us as well that Thoreau thought that the carrion vine lived up to its name, since according to her, he claimed: “ ‘It smells exactly like a dead rat in the wall, and apparently attracts flies like carrion. . . . A single minute flower in an umbel, open, will scent a whole room.’ ” She advises us not to pick Mentha arvenis, the corn mint, “a gift of Europe to our spacious wild, [whose leaves] when bruised smell like stale cheese. If you gather it because of its pretty dark rose-coloured blossoms that appear in the late summer your regret will last until you reach home and can thoroughly wash your hands.”

At the other end of the olfactory spectrum is, of course, the queen of flowers:

Fragrance is the rightful heritage of the Rose, and it is what we consciously or unconsciously expect of it. We cannot dissociate fragrance and the Rose. If you doubt this, watch the visitors at any Rose show bobbing forward automatically before each exhibit to inhale the fragrance and plainly registering by word or look pleasure or the reverse as the response they receive. . . . Of late, there has been uneasiness among flower lovers because of the numbers of scentless, or nearly scentless, Roses now appearing on the market. It is hard to believe that a scentless Rose could have great vogue, but there is that chill and soulless beauty, Frau Karl Druschki, to the contrary notwithstanding.

The curse of scentlessness is sometimes removed when the modern hybrid roses are crossed with old roses. Wilder’s language then rivals that of the wine connoisseur when she describes certain hybrids of intricate and complex old-rose ancestry. In one instance she invites us to smell and detect “the odours of spice and musk and of honey, even that of Violets . . . and a whole gamut of fruity odours.”

Like Jekyll, Earle, and other garden writers who grew up playing in a garden, Wilder’s happy recollections of her youthful associations with nature and place reinforce one of the themes running throughout these pages: if there is such a thing as a horticultural gene, it is powerfully nurtured by the privilege of having been born into a gardening family and having lived in a home with a beautiful garden. In citing a repertoire of fragrant roses, Wilder says:

In the Maryland garden of my youth we grew only Teas and Noisettes and I remember that splendid Rose of the latter class, Maréchal Niel, that wound a vigorous wreath about the library windows, was called the Strawberry Rose, because its pointed golden buds so realistically suggested the pungent odour of ripe Strawberries, and that the Tea Rose, Safrano, my mother’s favourite, had distinctly the spicy breath of the Scotch Pinks that edged the bed. . . . The Box bushes grew tall in my grandfather’s garden in Massachusetts, which has been little changed in outline for more than a hundred years. Their sharp scent seemed to bring about a special atmosphere of apartness and mystery, and when mingled with the simpler scents of herbs and the old time Roses, after a shower or an early frost, the odours of this lovely old garden would be raised to such a pitch of oriental richness that one felt transported straight out of green and white New England to the glamorous East. And to a small person creeping through the white gate to play, the usual game of young matron tidily keeping house beneath the Grape vine and competently managing a large family of dolls, seemed no longer fitting. Instead a distraught lady out of the Arabian Nights glided with lissome grace up and down the straight paths, a fantastic head dress of Hollyhocks masking pigtails, a Lily scepter in her hand.

Thus are the imprinted memories of childhood the future gardener’s lucky inheritance.