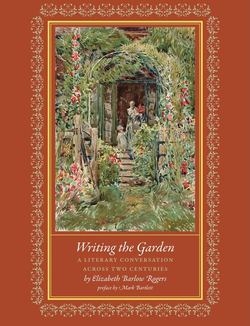

Читать книгу Writing the Garden - Elizabeth Barlow Rogers - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Jane Loudon

ОглавлениеI would categorize Jane Loudon (1807–1858) as a pioneer on behalf of women gardeners as well as a botanical and horticultural educator of the first rank. Mrs. Loudon (she is thus referred to on the title pages of her books) was the wife of the Scottish botanist John Claudius Loudon (1783–1843), author of An Encyclopedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening (1822). J. C. Loudon furthered the nineteenth-century marriage of industrial technology and horticulture with the invention of the hinged sash bar that made possible the construction of conservatories and glasshouses for the protection and propagation of the tender exotic plants pouring into England from the four corners of the world. He is best known as the originator of what is called the Gardenesque style, based on the arrangement of plants in a manner intended to display their characteristics as individual specimens.

A pioneer of science fiction like Mary Shelley, as Jane Webb (her maiden name), she anonymously published The Mummy! Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century (1827). Because of her descriptions of the kind of futuristic technological inventions that fascinated him, Loudon discovered the author’s identity and arranged a meeting. After their marriage she served as her husband’s amanuensis for the production of the rest of his herculean literary output, including the magisterial Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum (1838). Remarkably, she found time to become a botanical and horticultural writer herself. In Instructions in Gardening for Ladies (1840) and The Ladies’ Companion to the Flower Garden (1841), she gently nudged her purportedly delicate female contemporaries to take up the spade and trowel and to dig and plant as a source of healthy exercise and self-fulfillment. Since the ladies to whom her words are addressed were so unaccustomed to manual labor of this sort, she felt compelled to explain that “The first point to be attended to, in order to render the operation of digging less laborious, is to provide a suitable spade; that is, one which shall be as light as is consistent with strength, and which will penetrate the ground with the least possible trouble.” In that era of normative female attire, it was necessary as well to suggest the appropriate costume for a lady gardener: “a pair of clogs . . . to put over her shoes; or if she should dislike these, and prefer strong shoes, she should be provided with what gardeners call a tramp . . . . She should also have a pair of stiff thick leathern gloves, or gauntlets, to protect her hands. . . .”

“A Lady’s gauntlet of strong leather, invented by Miss Perry of Stroud, near Hazlemere.” Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Ladies’ Flower-Garden by Mrs. Loudon, 1860.

“Tigridia pavonia. Common Tiger Flower.” The Ladies’ Flower-Garden of Ornamental Bulbous Plants by Mrs. Loudon, 1841.

“The splendid colours of this flower and the easiness of its culture render it a general favourite. Its only faults are, that its flowers have no fragrance, and that they are of very short duration. It is a native of Mexico, where it is called Ocoloxochitl. In its native country its bulb is considered medicinal; and it was on this account that it was sent to Europe by Hernandez, physician to Philip II of Spain, when he was employed by the Spanish government to examine into ‘the virtues’ of the plants of the New World. It has been also found in Peru. It was not introduced into England till 1796. The bulbs should be planted in the open ground in March or April, when they will flower in May or June, and they should be taken up in September or October, and tied in bunches, and hung in a dry place till spring. They are sufficiently hardy to be left in the ground in winter, were it not on account of the danger to which they are exposed from damp; and consequently if they can be kept quite dry they may remain in the ground. They will grow in any common garden soil, moderately rich, and not too stiff; but they succeed best where there is a mixture of sand, to allow of the free descent of the roots. When grown in pots, the soil should be sand and vegetable mould, or loam. The bulbs produce abundance of offsets; and the plants ripen plenty of seed, which it is worth sowing, as, contrary to the general habit of bulbs, the seedlings will frequently blossom the second year. Whenever the Tigridias are planted so as to form a bed, care should be taken to give them a back ground of grass or evergreens, on account of the great gorgeousness of their colours.”

“Papaver orientale. Oriental Poppy.” The Ladies’ Flower-Garden of Ornamental Perennials by Mrs. Loudon, 1843.

“This is the handsomest of all the poppies. The flowers are very large, still more so than those of the preceding species, but in other respects at first sight they are scarcely to be distinguished asunder; though on closer inspection, it will be found that the hairs on the calyx and stem are closely pressed in a slanting direction, while those of the previous species spread horizontally. It also flowers a little earlier. It is a native of Mount Caucasus, and was introduced in 1817.”

I particularly treasure my copy of Mrs. Loudon’s My Own Garden; or The Young Gardener’s Year Book (1855), a charming, small volume illustrated with exquisite hand-colored engravings depicting flowers of the four seasons. Her magnum opus, The Ladies’ Flower-Garden (c. 1855–59), a five-volume botanical masterpiece, is much more than a book for women gardeners or children. Indeed, with its three hundred chromolithograph plates and detailed descriptions of more than a thousand species in various categories—bulbs, annuals, perennials, greenhouse plants, wildflowers—it ranks as one of the most beautiful, useful, and readable botanical encyclopedias of all time. The fact that Jane Loudon’s Christian name was never used in ascribing the authorship of this or her other books, and that her principle role was that of her husband’s amanuensis, should not obscure the fact that his star pupil was his peer in terms of horticultural and botanical knowledge and literary productivity. Accompanying every plate depicting related individuals of a particular flower species are comprehensive accounts of each one’s appearance, botanical structure, growth habit, native origin, medicinal and other uses, and horticultural requirements. When I once saw a set of these sumptuous volumes in the library at Garland Farm in Bar Harbor, Maine, the final home of the pioneering landscape garden designer Beatrix Farrand, I realized that, unlike some other books containing exquisite botanical illustrations, The Ladies’ Flower-Garden could be a useful reference tool for professional as well as amateur gardeners, an observation that still holds true today.