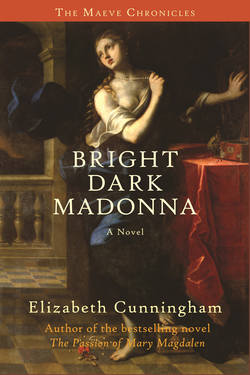

Читать книгу Bright Dark Madonna - Elizabeth Cunningham - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FOUR

WHAT MEN ARE FOR

“GET USED TO IT, MAEVE.”

The voice is my beloved’s, just as I remember it, rich as spring earth warmed by strong light, but when I sit up, the moonlight is thin and the air is cold. I look around the rooftop where I prefer to sleep. The other sleepers, servants mostly, don’t stir.

“Get used to what?” I say aloud.

But there is only silence and loneliness. I lie back down and pull the covers around me, and maybe it is my imagination, but I feel warm, warm as if I were not sleeping alone.

“There, that’s better.” His voice envelops me again. Maybe I am dreaming. What does it matter?

“Why can’t I see you?” I ask him, silently now.

I feel the warmth not just around me but all through me, as if the sun shone inside me, as if my bones were radiant.

“We are too close, Maeve. Our flesh is one. Don’t you remember? Don’t you know?”

“Our flesh has made flesh,” I tell him.

Then I sit back up again, shivering. I want to sink back into that warmth, the place where I am not missing him, where he is not missing, but I remember I have a bone to pick with him. Well, we fought all our lives. I don’t know why I expected it to be any different after death—or after death, resurrection, and ascension (if you must call it that).

“Now that I’ve got your attention, what the hell are you thinking, trying to marry me off to your brother?”

“Lie down, cariad.” I cannot resist his voice, the pull of his warmth. “That’s what I’m trying to tell you. You’re going to have to get used to people having visions of me, receiving messages from me. It seems to be a side effect of the god-making death, as you call it. The druids never warned me about it.”

“Side effect? I think you’re trying to sidestep the issue. Did you or did you not appear unto your brother James and speak unto him that load of crap about his duty to your lineage?”

“Not a load of crap, Maeve. Levirate. It’s in the Law. James might have thought of it himself, even if I hadn’t appeared to him. He’s always done the right thing.”

“But did you tell him to marry me!” I was insistent.

“That’s what I’m trying to explain, Maeve, I can’t help appearing unto people when they call on me, when they believe in me. I might even speak unto them, but remember what Anna the prophetess used to say about prophecy, how it always loses in the translation and gains in the interpretation? It’s like that, and I’m afraid I don’t have much control over translation or interpretation.”

“What? Can’t you speak plain Aramaic anymore?”

“It’s not that simple.”

“So what did you say unto James.”

“I apologized to him. He was feeling badly for resenting me all my life, so I wanted to tell him: it wasn’t your fault. I left you holding the bag. I was free, because you took care of all my responsibilities as well as your own. I told him: you’re the true son of David, not me. Enjoy your life; enjoy the fruits of your labors. Well, you know how it came through to him. Listen, Maeve, I’m warning you, this god-making death has unforeseen consequences. It’s only just beginning. I don’t know what’s going to happen. I only know it’s not over.”

I say nothing for a moment, considering. What my beloved says makes a kind of sense. People hear what they want to hear. James, being duty-driven, hears that he has a new duty. As for the fruits of his labor—picking up his half-brother’s slack all his life—well, why shouldn’t he become a leader in this new cult centered on his brother? Why shouldn’t he be the one to foster the heir?

“I see,” I answer; then I add in honesty. “Sort of.”

I don’t want to talk about James anymore. I just want to melt into the feeling of him being melted into me.

“But it’s not such a bad idea,” he says, a little hesitance in his voice.

“What isn’t?”

“Marrying, James.”

“Jesus!” I sit up again, and lose my sense of him. “No, don’t go.”

I lie down and nestle back into his warmth.

“You’re going to need someone to protect you and our child. I may have had my own problems with translation and interpretation when I prophesied, but terrible times are coming to Judea. And what’s so bad about James? When you were a priestess, you received so many god-bearing strangers.”

A polite way of saying: when you were a whore, you took all comers.

“Jesus,” I say again. “If James were a god-bearing stranger at the gates of Temple Magdalen, of course I would receive him. But I don’t want to marry him—or anyone. I barely managed being married to you, for Isis’s sake.”

I can feel him smiling—a sense of being gently tickled all over from the inside.

“And for Christ’s sake,” he suggests. “People are going to start saying that now.”

“Oh, for Christ’s sake,” I try it out. “What do you want me to do, cariad? Do you seriously want me to marry James?”

“Would you? If I told you to?”

I thought about it for a moment, tried to imagine being the wife of a righteous, humorless man living, as James put it, in modest retirement in Nazareth with my mother-in-law. Even more disturbing is the idea of my (late?) husband giving me orders and expecting to be obeyed. That would be a most unfortunate side effect of the gmd (god-making death).

“No.” I answer simply. Well, if he is a god, not much point in lying, is there?

Now he is laughing. My body rocks with it.

“What will you do, my dove?” he asks with such tenderness I almost weep.

“I don’t know, cariad,” I confess. “But I won’t let anyone take my child from me. Not again. Not this time. You must know that.”

“But if you had to choose between keeping the child and keeping the child safe?”

“Don’t you start with the bulrushes. Give me a chance, for Isis’s sake, for Christ’s sake, for my sake. Just give me a chance. Have some faith in me.”

“I do have faith in you, Maeve. Who, more than I, knows who you are.”

“You still talk too much,” I tell him. “Just hold me for awhile.”

“Always.”

In case you have forgotten, let me remind you now: Love is as strong as death. Stronger.

Word of my pregnancy, and of James’s offer of marriage or protection, spread to Jerusalem and beyond very quickly. By the bird’s wing, as the Aramaic expression goes. So I was not surprised when my old friend Joseph (yes, of Arimathea) came to visit me in Bethany a few days later. I would have expected him to come in any case. He had been trying to rescue me, or at least improve me, since we met more than a decade ago at the Vine and Fig Tree in Rome where I was a popular whore.

Lazarus had just finished the late summer shearing. I was sitting with Miriam and Susanna in a shady corner of the yard, carding raw wool while they spun, the latter skill being beyond me. I was as unschooled in the domestic arts as Mary B, though for different reasons. While she spent her childhood poring over the Torah, I was being overindulged by my eight mothers, who themselves were more concerned with the warrior arts. When they thought to impose a discipline on me, it was usually to practice spear throwing or to learn to grease the harnesses for the battle chariot. So in Bethany I was given tasks that would ordinarily be given to a young child. I wasn’t bored, exactly, just lulled into a stupor. It was hard to stir myself when I saw Joseph approaching. He seemed another part of a long dream that kept going on and on.

“Ladies,” he greeted all of us, but his eyes rested on me. “I hope I find you well.”

“It is always pleasant to see you, Joseph of Arimathea,” said Ma who did not usually bother with niceties. “You mean well,” she added obscurely. “Everyone knows that, even the Most High God in whom you do not believe.”

“Joseph,” Susanna intervened. “Sit down. I will let Martha and Lazarus know that you’re here. Miriam, come with me,” she said as commandingly as she dared.

“If you like,” said Ma airily. “You mean well, too, Susanna. But it won’t make any difference, you know. The angels told me so this morning.”

“Save me!” I muttered when Ma had drifted after Susanna out of earshot.

“I thought you’d never ask.”

I turned to Joseph with a smile, and saw that he was dead serious. I looked at him, really looked. He appeared haggard; it struck me that he had aged since I had last seen him a few months ago, only days after my beloved’s death and whatever you want to call what happened after. Joseph had thought my story was crazy, that I was crazed with grief and in what you would call denial.

“Maeve, he’s dead!” Joseph had wrung his hands when I told him that Jesus had asked me to take the disciples to meet him in Galilee. “You’ve got to accept it!”

“No, I don’t,” I ‘d said blithely. “What about you? When are you going to accept that the tomb is empty?”

“Maeve, listen to me, this is serious. If Peter and the rest moved the body in order to fulfill some bizarre piece of prophecy, they are playing a very dangerous game.”

“They didn’t, Joseph. Don’t you get it? They don’t believe me, either. But I’m telling you Joseph, I was there with him in the garden outside the tomb, and if seeing Jesus was just a vision or a dream, it makes no difference to me.”

“Fine then, you had a vision. Why can’t you leave it at that? Why involve his followers? Wherever there’s a crowd of them, there’s going to be trouble. You’ve done all you can for your beloved husband, may he please rest in peace and not cause any more problems,” he’d pleaded. “You need a change. You need a rest. It’s dangerous here. And it’ll be even more dangerous, if you go around insisting that he’s not really dead.”

“It’s no use trying to talk me out of it, Joseph. I’m going to Galilee with the others, if they’ll come,” I’d said. “I’m going home to Temple Magdalen.”

“Well, stay at Temple Magdalen then, and stay out of Jerusalem. At least you should be safe there,” he had finally conceded. “For the time being.”

So we had parted, Joseph with great reluctance, and me with no thought of anything but meeting my beloved in Galilee as he had promised. Jesus had kept his promise. And when he asked me to bring the disciples back to Judea, I did. So here I was again with more trouble brewing, just as Joseph had predicted—Peter and some of the others had already been imprisoned and released more than once.

And here was Joseph back from Alexandria. A place you could get to and from by boat. He was not wandering in the Otherworld or talking in the small hours of the night inside my head, or making appearances unto others that he couldn’t seem to control. How comforting to sit with an ordinary man. Though Joseph was almost completely bald now, his face, clean-shaven in the Roman style, lined and a bit pouchy, no aging could alter the intelligence and kindness of his eyes. I was glad to see him again.

“How are you, Joseph?” I said, touching his cheek. “You look tired.”

“I am tired,” he said, his voice low. “Tired of waiting for you, though I will go on waiting—”

“Joseph,” I tried to interrupt.

“No, Maeve, hear me. I must speak. I know I have failed you in the past. Acted selfishly.”

I must have looked puzzled, for Joseph paused, saddened rather than relieved to see that I had forgotten his transgressions. I understood and felt sad for him. He had been telling himself the story of Joseph and Maeve, and despite my great affection for him, I had never paid much attention to that story.

“Joseph, my friend, I will search my memory for your failings if you ask me to. But what I remember best is how you have always held out your hand to me with no thought of your own gain. Smuggling me out of Rome with my friends, helping me to found Temple Magdalen, presiding at my wedding feast, defending Jesus in the Sanhedrin. No one could ask for a truer friend.”

“Maeve, you know I love you.”

“I love you, too, Joseph.”

“No. Maeve. Listen. I love you. Selfishly. You may have forgotten, but I haven’t: How I told no one in Bethany that you were still alive and enslaved in Rome, no one who might have told Jesus. And I knew very well that he thought you were dead. I confessed it to you long ago, that time I tracked you down at Paulina’s villa and tried to buy you away from her. Do you remember now?”

“Yes, Joseph, I remember.” I added no excuses for him, no protestations that I had forgiven him long ago, though I had.

“Do you remember what else I confessed?”

I didn’t respond. I guessed what was coming.

“I wanted you for myself.” He paused a beat. “I still do, Maeve.”

There were things I knew I could say, excuses I could make. It’s so soon. I’ve only been a widow (if that’s what I am) for four months. Things that would make Joseph wrong for pressing me, that would make him apologize or back away, head him off from where I sensed he was going. Then maybe I could keep my friend Joseph at my beck and call, as he had been all these years. But it would not be a kindness to this man who had been nothing but kind to me, and who was trusting me with his truth.

“I know, Joseph,” I said.

And there seemed nothing more for me to say. So we sat in silence for a time, the afternoon light slanting and the mourning doves calling and calling.

“Maeve,” he said at length. “I know you have always loved him. I know you cannot love me, or anyone, as you loved him. I am not a fool—or maybe I am where you are concerned, but I am not deluded. I can offer you my love. I can marry you, if you will have me. I can make a home for you anywhere in the world—far from here, I hope. I can love and protect your child. And I can understand, as no other man could, that you love him still. Don’t forget that I witnessed that love almost from the beginning.”

It was true. Joseph, on business in the Pretannic Isles, had met Jesus just after he escaped from Mona. He had been with Jesus when the priestesses of Glastonbury informed him that the druids had exiled me alone in a small boat “beyond the ninth wave” as punishment for interfering with the mysteries (i.e. human sacrifice aka the god-making death). Joseph had agreed to attempt a search for me, but then the terrible storm came and with it their certainty of my death. By sheer chance (or not) Joseph had encountered me in a Roman brothel three years later and had pieced our stories together.

“Oh, Joseph” was all I managed to say, and I turned to him and pressed my face against his heart.

“Maeve,” he murmured, dropping kisses on my head, “Maeve, may I hope—”

I realized my mistake and gently drew myself apart. Joseph looked away abruptly, but not before I saw the pain. It’s done now, I thought, it’s over. But it wasn’t.

“You received me as your lover when you were a priestess,” he spoke tersely, not looking at me. “Was it…was it charity? Obligation? Obedience to the goddess?”

“And to the god.”

Isis, I prayed. You called me to be your priestess. Help me now to heal the wounds I never meant to inflict.

“The god in you. Look at me, Joseph,” I commanded in her voice, and he obeyed. “What do you see?”

I didn’t know the answer myself. I only knew he had to see it and say it for himself. He looked at me, and I looked back. I saw his face change, hurt and longing giving way to surprise, maybe even awe. Then at last there was sadness again and love.

“I see, Maeve,” he said.

What do you see? I wanted to ask again, not in her voice this time, but in my own human confused voice. Yet I held my peace.

“You won’t come away with me,” he stated. “You won’t let me make it easy for you. Or safe. You won’t let me save you. That’s not what you want. It never was; it never will be.”

I felt him let go, move away. In my mind I saw his boat, leaving this shore, leaving this story. And I could go, could have gone. Any moment it would be too late.

“Joseph.” I called out as if over the waves, over the wind.

“Shh! Maeve. I’m still here. Shh!”

He reached for me, and I clung to him, not like a lover but like a child. Joseph understood and held me close.

“I have to ask you one thing, Maeve,” he said after a moment. “Although my pride wishes I wouldn’t.”

“Ask anything,” I said, letting go of Joseph.

“I know that James the brother of Jesus is claiming the right of levirate. Are you—”

“Sweet Isis, no!”

“Well, I thought…I thought you might want to marry his brother…to stay close to him. To be with someone who reminded you of him.”

“Joseph, have you met James?”

“At the wedding. Oh, yes, I see what you mean. No family resemblance at all.”

“None.”

“I told you I was selfish,” said Joseph. “I won’t pretend I’m not glad. But I am also worried. Who is going to protect you, Maeve? You and the child?”

“Who” must mean what man? Apparently that was what men were for. Even my beloved had said it: you need someone to protect you, you and the child. Who else but a man? A husband? Yet life hadn’t taught me what seemed so obvious to others. I had grown up without a man in sight. I had lived with whores and priestesses most of my adult life. I had finally married a man who had no home, no wealth, and no idea of how to protect himself, let alone anyone else. Pardon me if I remained clueless.

“I don’t know, Joseph. I don’t know. Have...have faith in me?” I suggested

But the words didn’t sound as convincing as they had in my dream conversation, and Joseph looked dubious.

“Maeve,” he said at last. “Listen to me. I won’t ask you again to be my wife, but please hear me. I have to make a voyage to look after my interests in Pretannia. You could come with me. Just come. You could go home to your people.”

I closed my eyes, the sense of homesickness was so sharp, so unexpected. I could hear the sound of the sea, smell it, see the spray of waves breaking on rock, catching the light, hear the sound of gulls. And inland the darkness, the greenness, the huge oaks.

“Joseph,” I spoke with effort, as if in a dream. “I am an excommunicate, an exile.”

“That was long ago now, Maeve. No one will remember.”

“Joseph, surely you’ve met druids. Remember is all they do.”

I opened my eyes, and here I was again, in Martha’s courtyard, the heat of the afternoon just beginning to turn, the dusty olive leaves making their dry sound in the breeze. Then I heard the humming sound, bees in apple blossoms on the Shining Isle of Tir na mBan, or the wild roses of Temple Magdalen.

It was only Ma carrying a tray of food, a little haphazardly, scattering figs and olives as she listed across the courtyard.

“I sail in three days, Maeve,” said Joseph softly. “Send me word, if you change your mind.”

And though Joseph stayed to eat with us all, as the rules of hospitality demanded, I knew in my heart—in his heart—he was already gone.