Читать книгу Bright Dark Madonna - Elizabeth Cunningham - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TEN

MY PEOPLE

Ave Matres

Hail all mothers

graceful or not

God or goddess is with you, believe it or not.

Blessed are all women

and blessed are the fruits of our wombs

whatever names, ridiculous or not, we choose for them

and even when they’re acting rotten.

O mothers

holy human mothers

all our children are divine.

Long after they leave us

they will curse us and pray to us

now and in the hour of our death

now and in the hour of their need.

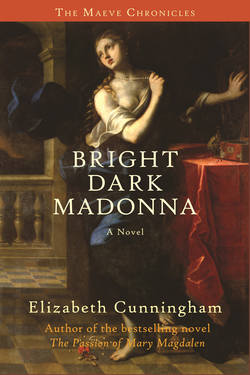

I HAVE TAKEN THE LIBERTY of making this famous prayer to my mother-in-law a paean to all mothers—myself included. I am about to become a mother again. I am the bright dark madonna of this story, the daughter of mothers, bright and dark, the mother of daughters bright and dark. I take my place, however hidden, in the lineage of madonnas, Mary the mother of Jesus, Isis the mother of Horus, Demeter the mother of Persephone. Mother of a child or child of a mother, you are part of this lineage, too, this holy human lineage, the origin of bliss and loss.

Of course, I did not think about any of that then. I had tunnel vision. The only thing that mattered was getting home to Temple Magdalen, the only home I had ever made. In my heart, I had never left it.

Ma and I arrived just at first call of the Sabbath shofar. The gates stood open, and I paused, relishing the sight of home: whores and children singing the evening hymn to Isis; Judith and various helpers hurrying to lay out all the food before the third call of shofar sounded. Cats stretched, strolled, or lolled; chickens scratched the dirt and strutted. Old men entertained the bedridden with dice games, while old women scolded them for being in the way. On one of her trips back and forth, Judith caught sight of us and dropped a tray of figs. “Aren’t you just like him!” she complained and exulted. “Always showing up just when it’s time to eat!”

Shabbat dinner at Temple Magdalen was one of our untraditional traditions. Our creed, to the extent that we had one, was to celebrate all and any holy days, especially if it involved eating and drinking. Judith, who was Jewish and not, by the way, a whore, knew all the Sabbath songs and blessings, so she presided over the table, so to speak, which really meant all of us sitting on the ground together in a big circle, reaching into common dishes, passing wineskins around and around, torchlight and starlight lighting our faces, the air alive with jokes and laughter.

After dinner, when our bellies were full, there would come a lull as people settled back, leaning against each other, sometimes dozing a bit, and generally digesting. I gazed around the circle, content to let everything be a little soft and blurry. Judith had taken charge of Ma, who rested her head on Judith’s shoulder. Reginus, once my fellow slave in Paulina’s household, reclined with his lover Timothy spoon fashion. I had my head in Berta’s soft, abundant lap, while Dido, my other sister whore, massaged my feet. I had met them both at The Vine and Fig Tree, the Roman brothel where I was first a whore. But all these stories I have told before.

At the moment, you only need to know I was with my best friends, all of us exiles of one sort or another. Their friendship sustained me through all the years of longing and looking for my beloved. When Jesus appeared at our gate, more dead than alive, my friends rejoiced with me. They welcomed him and came to love him, too (Dido held out the longest), but I’ll tell you a secret: they loved me more. When I left to wander with Jesus, they loved me enough to let me go, and the life of Temple Magdalen went on in its quirky, practical, joyful way, whether I was there or not. That “way” never turned into an institution; it was, in some sense, the antithesis of an institution—which is why it was so wonderful, which is why you have never heard of it.

After Sabbath dinner, we usually told stories, and in time I became aware of people turning toward me expectantly. I had been away for six months and turned up with a round belly, an eccentric mother-in-law but none of Jesus’s followers, whose company I had kept for more than two years.

“Well,” Reginus prompted. “Are you going to tell us everything or what?”

A little ungracefully, I sat up and rearranged my belly so that it rested between my crossed legs. I put my arms around the roundness and balanced it in my hands.

“Yes,” Reginus acknowledged my centerpiece, “you are just about what I’d call perfectly pregnant. Does he, did he know before he….” Reginus trailed off uncertainly.

I opened my mouth, but no words came out. I realized, for the first time, that I had never told anyone, anyone in the world, what had happened in the tomb, how the love that is stronger than death had led to new life in the most literal and intimate sense. Nor had I told my beloved, in so many words, what I was beginning to suspect just before he disappeared through the Beautiful Gates.

“I, I don’t know. I mean I think he does …When he—”

How to say it? When he talks to me from inside my body, my blood, my bones… I found that I couldn’t go on. I was the daughter of eight mothers, who spun wild, contradictory tales on the slightest provocation, and I suddenly had no story. Or I did not know how to tell it, not this part. No wonder I’d had so much trouble among the disciples. They were all busy telling his story, deciding what it meant, what parts to keep and what to forget, how it fulfilled this or that bit of scripture, and I was still tongue-tied.

He was dead, and I bathed him with whores’ tears, and then we made love all night all day all night till the earth shook and the stone rolled back, and there we were under the tree of life at the dawn of the world.

I looked up, dazed.

“Better get the vial,” Dido, said to one of the younger whores. “It’s on the altar.”

“Liebling,” Berta had her arm around me. “What happened to you in Jerusalem? We’ve been so worried, and when Joseph sent for Paulina, we knew something must be wrong.”

I started to shake, and Berta held me closer.

“She’s too tired to talk,” said Dido across me to Berta. “We ought to get both of them to bed.” She nodded towards Miriam. “Come on, honey.”

“No,” I said, “not yet. I need to tell all of you something. I ran away.”

And I registered it, as if for the first time. From the moment I bolted from the Jerusalem house I had been on a mindless trajectory, bent only on coming to safety, a bird tossed into a storm wind, flying blind. Now here I was, finally still, and some truth, some grief that I couldn’t yet name was catching up to me.

“They want to take the baby from her.”

Miriam’s voice startled everyone, as if the fire had spoken up, or the spring. A gust of sympathy and outrage went round the circle.

“Do they know you’ve come here?” asked Timothy, clearly worried.

“Where else would she go?” Berta demanded. “This is her home, we are her people.”

My people. All at once I knew what was troubling me, beyond the instinctive fear that had driven me here. I had fled from Jesus’s people without a backward glance, the ones I loved, Mary B, Susanna, Tomas, Lazarus, and the ones I loved who didn’t love me, Peter, Andrew, Matthew, well, to be honest, most of them. Once not so long ago, my people and his people had gotten sublimely drunk together and danced at our wedding feast. I had called Jesus’s disciples my companions, I had shared the pleasures and hardships of the road with them, I had wept with them over his body. And so quickly they had become my enemies. Or I, theirs.

“She feels guilty,” Miriam announced bluntly. “And yet, Holy Isis, my daughter-in-law thinks she’s not Jewish.”

No one seemed to know how to respond to that remark, so we left it to Isis.

“Don’t worry, honey,” Reginus came and knelt behind me, his arms around me. “We’ll protect you.”

Just then the young whore, who was new to Temple Magdalen, returned carrying the vial in her hands next to her heart, gazing at me with a love and reverence that perplexed me until I remembered what Susanna had told me about Dido and Berta’s training methods. Apparently, they told aspiring whores my story, as I had once told it to them in the whores’ bath in Rome, as that story had unfolded, leading to us all to Temple Magdalen. I smiled at the dark, round-faced young woman as she held out the vial to me.

Dido and Berta had sent me the vial just before Jesus was arrested. I had poured out every last drop in the tomb, bathing his every cut, washing his mortal wound.

“Whores’ tears,” Old Nona had said. “Cure anything.”

When I had returned to Galilee with the disciples, I had brought the vial back to Temple Magdalen. Now I held it in my hand again, gazing at it till I couldn’t see. Then I unstopped it, handed the tiny blade to the young whore and let her harvest my tears.