Читать книгу Antiquity in Gotham - Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis - Страница 19

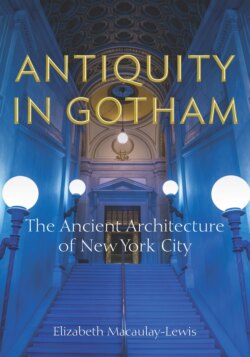

The Parthenon on Wall Street: The US Custom House

ОглавлениеIf one walked east from Trinity Church in 1915, crossed Broadway, and arrived at the intersection of Wall and Broad Streets, one could be excused for believing that one had accidently stumbled into an ancient Roman city. On the right is a Corinthian temple–like building that houses the New York Stock Exchange, across from which is an austere, squat building decorated with a few classical details, once the headquarters of J. P. Morgan. On the left, one would pass the Bankers Trust Building at 14 Wall Street, which had an Ionic colonnade at street level and a step pyramid for a roof (discussed in the next chapter), and arrive at 26 Wall Street, where stood a Parthenon-like, octastyle Doric temple that one would expect to find atop the Athenian Acropolis. Rather than serving as a temple to Athena, the building is the US Custom House, also known as Federal Hall.

The site is rich with history. In 1704, a new Georgian-style city hall had been built here, replacing the old Dutch Stadt Huys on Pearl Street. In 1788, Pierre L’Enfant, who planned the grid of Washington, DC, remodeled the building, converting it into the nation’s first capitol building. Rechristened Federal Hall, George Washington was inaugurated there as the first president of the United States on April 30, 1789. The much-celebrated building met the same fate that so many of New York’s historical buildings have; New Yorkers demolished it in 1812 and erected rowhouses in its place.13 While New York was busy replacing historical structures with functional, mundane architecture, other cities, such as Philadelphia, embraced Grecian architecture, which embodied the young nation’s democratic principles, for their civic and bank buildings. Benjamin Latrobe’s Ionic-style Bank of Pennsylvania was constructed between 1798 and 1801. William Strickland, Latrobe’s pupil, erected the Second Bank of the United States (1819–1824), which was the first Parthenonesque public building in the nation and still stands today in Philadelphia. These buildings established the classical temple as a model for civic and banking buildings, and this trend would reverberate across the United States. The Virginia State Capitol (1785–1788), designed by Jefferson, is modeled on the Maison Carrée (Nîmes, France), the world’s best-preserved Roman temple (see Figure 30).14 The original United States Capitol that burned down in 1814 was classical as well.15

The Parthenon, arguably the most famous temple from the Greek world, was a suitable model (Figure 13). Located atop the Acropolis, it was dedicated to Athena Parthenos, the patron goddess of Athens. In the fifth century BCE, Athens became the first democratic state in the world, giving male citizens the right to vote, serve on juries, and administer the city’s government. Furthermore, in a series of remarkable battles at Marathon, Salamis, and Plataea between 490 and 479 BCE, Athens and its allies achieved the unthinkable: They defeated the Persian Achaemenid Empire, the superpower of the ancient world, and ensured their freedom and the continuation of their radical democratic experiment. Athens was thus an ideal political model for the new United States, which had recently thrown off the tyranny of the British Empire.

FIGURE 13. Parthenon, Athens, 2012.

Source: S. Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Knowledge of monuments such as the Parthenon reached Americans through archaeological publications.16 Of these publications, none was more important than The Antiquities of Athens (1762–1816) by James Stuart and Nicholas Revett. This richly illustrated, four-volume publication brought the Parthenon and the Erechtheion (also on the Athenian Acropolis), as well as other artistic and architectural achievements of Athens and the classical Greek world, to Americans for the first time, providing architectural and artistic models for the democratic ideals, philosophies, and history that informed the founding of the new nation. While these books were expensive, copies were circulating in the United States; Jefferson’s books on architecture had been in the Library of Congress since 1815.17 The library of Ithiel Town, the architect whose work is discussed below, had an estimated 11,000 volumes and 20,000 engravings, to which architects, artists, and his friends had access.18

The Founding Fathers were classically educated.19 Classical culture pervaded the intellectual and civic life of the early republic, as a classical education was considered essential in creating informed citizens who could govern justly.20 Not only did the classics pervade the intellectual life and curriculum of colleges, but, as Caroline Winterer has argued, “classicism was an important part of … ‘civic culture.’ ”21 For example, Washington showed his troops the 1712 play Cato, by Joseph Addison, when stationed at Valley Forge. This play dramatized Cato the Younger’s principled opposition to Julius Caesar before his death, a suitable topic for the Revolutionary War era.22 Unsurprisingly, the architectural ideals of the new nation primarily took a classical—and predominately Greek—form.

In his 1842 address to the Royal Academy, C. R. Cockerell termed this architecture style, with its embrace of classical, predominately Greek architectural forms, the Greek Revival.23 The scholar Steven Dyson has challenged the definition of the revival as a properly “Greek,” arguing that the use of domes and the Corinthian order were more Roman than Greek.24 While Dyson is not incorrect—many of these forms were Roman—his interpretation overlooks several key points about the Greek Revival and its name. First, many of the architectural elements and motifs are Greek or first originated in Greece; they can be thought of as Grecian, that is, in a Greek style. Second, architects and critics of the time identified these forms as Greek. William Ross, an English architect who later worked as a draftsman on the Custom House, wrote in late 1835 that “the Greek mania here is at its height, as you infer from the fact that everything is a Greek temple from the privies in the back court, through the various grades of prison, theatre, church, custom-house, and state-house.”25 Third, the architects of the time were interested in creating archaeologically informed buildings, not accurate copies.26 The thoughtful modifications of ancient building types or the combination of Greek and Roman forms made the buildings original, American creations and led to the development of the Greek Revival style as the first truly national style of building.27

Then as now, New York City was the epicenter of the US economy. Between 1817 and 1825, the Erie Canal was constructed by the sheer will of New York’s governor, DeWitt Clinton. This watercourse connected New York’s bustling harbor to the Great Lakes and America’s newly settled agricultural interior, facilitating the flow of goods, services, and people. The canal made New York the largest, busiest port in the United States and spurred on the city’s growth. At the start of the Civil War, New York handled more than 60 percent of the nation’s exports.28 This was not only a financial boon to New York City but also to the US federal government. By 1852, 95 percent of the federal government’s revenue came from customs duties, the tariffs on imported goods, and New York City accounted for an astonishing 80 percent of this revenue.29

Between 1799 and 1815, the New York Custom House occupied Government House at Bowling Green. After 1815, the Customs Service was located in one of the rowhouses on the site of the old Federal Hall. In 1833, it was agreed that the US Customs Service needed a proper building, and Town & Davis was hired to design the new Custom House, reflecting the importance of such tariffs to the United States.

A talented engineer who had invented and patented the Town lattice truss for bridges (which made him a small fortune), Ithiel Town was one of the United States’ most important early professional architects. In 1827, he opened an office in New York City. In 1829, Town entered into a fruitful seven-year partnership with Alexander Jackson Davis. Davis was an exceptional artistic polymath—a draftsman, an architectural renderer, an engraver, and one of America’s earliest lithographers.30 In the early 1820s, around the time when Gulian Verplanck made his address, Davis studied at the American Academy of the Fine Arts and at the National Academy of Design, which counted Ithiel Town among its founders,31 and one wonders if Davis might have even heard Verplanck’s address. Clearly, ideas about Greek architecture were circulating in the creative milieu of New York City.

FIGURE 14. Original design, US Custom House, Manhattan, 1834.

Source: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The firm of Town & Davis was the McKim, Mead & White of its day, winning prestigious public commissions left, right, and center, including the Connecticut State Capitol (1828–1831, demolished 1889), the North Carolina State Capitol (1833–1840), and the Indiana State Capitol (1831–1835). They also had a hand in the erection of the Ohio State Capitol (1838–1857, with Henry Walters).32 These buildings embraced Grecian colonnades and Roman domes, affirming the popularity of such forms for America’s public architecture.

Town & Davis was responsible for the bulk of the design of the Custom House, which the secretary of the Treasury approved in 1833. In clear homage to the Parthenon, the original Town & Davis design included a double row of Doric columns on the building’s front and rear porches, triglyphs and undecorated metopes, and plain triangular pediments (Figure 14). Acroteria were intended to surmount the apex and corners of the triangular pediments on the front and the rear. The original plan was organized around a Greek cross with a high central dome and lantern that would be clearly visible on the exterior, which also evoked Rome’s Pantheon, with its blank pediment and vertical stacking of a triangular pediment and dome.33 The use of the Greek-cross plan also secularized a design historically associated with the Catholic and Greek Orthodox faiths. While the dome could be seen as a deviation from pure Greek forms, Town & Davis can be understood to be heeding Verplanck’s call to interpret ancient forms, here the Parthenon and, to a lesser extent, the Pantheon directly.

Construction began in January 1834, and Samuel Thomson, who worked on Snug Harbor, another set of resplendent Greek Revival buildings on Staten Island,34 was hired as the builder. Almost immediately, the US Customs Service instructed him to modify the building, ostensibly to rein in the skyrocketing costs. The central rotunda was deemed to be too large and the dome too structurally complicated.35 Consequently, the rotunda was scaled back and moved toward the front of the building (on Wall Street), and the reduced dome was no longer visible on the exterior. Each portico received a single colonnade rather than a double.

From the start, Thomson’s tenure was filled with tension. So when his responsibilities (and pay) were abruptly reduced by the US Customs Service, he quit in April 1835 and made off with the plans. In July 1835, the stonemason-turned-architect John Frazee was hired as Thomson’s replacement. Frazee had to draft his own plans to follow the already-laid foundations and cut stone. His influence on the design is most evident in the interior, the detailing, and his transformation of the third floor from a storage attic to a full office floor. Imported thick French glass, which resembled marble, was fixed in the metopes of the entablature, providing light to the third-floor offices.36 The building was composed of matt white marble, which was shipped from nearby Eastchester.

In 1842, the Custom House (192 × 90 feet) finally opened (Figure 15). Nassau Street slopes down sharply between Pine and Wall Streets, giving the Custom House an imposing air. Its portico is reached by a steep set of stairs; one can imagine a merchant, arriving for the first time in New York, climbing the staircase to pay his customs duty in surprised awe at the classical temple that greeted him. The pediment had no sculpture. Although some contemporary buildings had simple carved pediments,37 the lack of sculptural decoration may have been an aesthetic choice, which Francis Morrone has argued might have reflected a “romantic cult of ruins.”38 Given the economic realities and lack of qualified sculptors, such a decision was an easy choice.

Behind Doric porticos, one would expect a rectangular space, like the cella of a classical temple. Instead, a visitor was greeted by an airy rotunda, evocative of the Pantheon, with a diameter of sixty feet, supported by sixteen Corinthian columns and eight pilasters, each twenty-five feet high (Figure 16).39 The fifty-four-foot dome with a skylight provided good natural light. This was the heart of the action: the collector’s room, which was filled with desks where tariffs could be levied, enriching the coffers of the United States. The second-story balcony’s iron balustrade was decorated with mermaids, a likely allusion to the trade that drove New York’s success.40

FIGURE 15. Wall Street façade, US Custom House, Manhattan, 2017.

Source: Author.

FIGURE 16. Rotunda, US Custom House, Manhattan, 2017.

Source: Author.

The US Customs Service outgrew its home at 26 Wall Street within a mere twenty years, moving to the former Merchants’ Exchange (1836–1842) at 55 Wall Street (discussed in the next chapter). 26 Wall Street then served as a federal subtreasury building until 1920. Despite its demotion in 1862, the building has remained an important historical site to this very day. In 1883, John Quincy Adams Ward’s outstanding bronze statue of George Washington was erected on a high granite plinth at the bottom of the steps on Wall Street to commemorate the centennial of the Revolutionary War’s end.41 In 1955, the building was renamed Federal Hall, and in 1965, it was landmarked. As a symbol of the early United States, Federal Hall has become a historic anchor in an ever-changing city. Since 1800, Congress has only convened outside of Washington twice. It met in 1987 in Philadelphia to commemorate the bicentennial of the ratification of Constitution, and on September 11, 2002, Congress met in Federal Hall to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Thus, ancient architectural forms still resonate as symbols of the nation’s pride, resilience, collective loss, and democratic values.