Читать книгу Antiquity in Gotham - Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis - Страница 20

Brooklyn Borough Hall, the Manhattan Municipal Building, and Foley Square

ОглавлениеThe US Custom House established classical forms as a leading style for civic buildings such as city halls, municipal buildings, and courts in New York City. Clearly, the classicism of the building lent authority to public buildings. While Manhattan’s City Hall looked to French architecture for its inspiration, Brooklyn appropriated classical forms for its city, then later borough, hall (Figure 17).

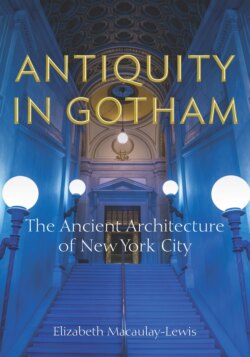

FIGURE 17. Brooklyn Borough Hall, Brooklyn, 2009.

Source: Jim Henderson (CC0).

In 1835, a year after Brooklyn became a city, plans were underway to erect a city hall.42 Located on a triangular plot edged by Fulton, Joralemon, and Court Streets, the building would symbolize Brooklyn’s status as a thriving city and provide much-needed space for conducting civic business. Calvin Pollard won the design competition, and the cornerstone was laid in 1836. However, like the US Custom House, the construction of Borough Hall progressed in fits and starts. Together, these two buildings followed a process that most New Yorkers would still recognize today: one dominated by inconvenience, cost overruns, inevitable delays, and, of course, a lawsuit. Almost immediately, the panic of 1837 and Brooklyn’s near bankruptcy halted the project. Construction resumed in the early 1840s, but only a bond issue of $50,000 in 1845 put the construction back on track. Gamaliel King, who was runner-up to Pollard in the design competition,43 was then hired to complete the building. Like Frazee, King faced the same challenge of designing a building whose foundation had already been laid. Modifying Pollard’s design, he used the already-cut light gray Tuckahoe marble (for which the contractor had been suing for payment for years)44 to create a fine, if not austere, Greek Revival structure, which was completed in 1851.

The rectangular, four-story building with its tall pilasters is an archaeologically informed building adapted to the needs of a thriving mid-nineteenth-century city. The focal point of the building is an elevated hexastyle portico supported by Ionic columns, each three stories tall, reached by a grand staircase. The undecorated pediment is akin to those of the US Custom House. Perched above the pediment was a wooden cupola topped by a statue of Justice. The cupola served as a fire lookout and bell tower until 1893. Ironically, in 1895, a devastating fire caused the collapse of the cupola; the bell and the figure of Justice unceremoniously crashed through the roof. A cast-iron cupola was erected in 1898. The new cupola with its undulating curves framed by columns seems to be modeled on the Temple of Venus at Baalbek, Lebanon (Figure 18), which was well known thanks to its inclusion in Louis Cassas’s Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoenicie, de la Palestine et de la Basse Aegypte (1800) and from mid-nineteenth-century photographs by Francis Bedford and others.45 The new cupola reflects the shift in preference from Greek forms to Roman.

The inclusion of the cupola also testifies to the lasting influence of Georgian forms on American architecture; European architecture was often an intermediary lens through which American architects accessed ancient art and architecture.46 The imposing portico dominates the building, and for those at street level it demands attention. To achieve the same effect vertically, the spire was necessary. In this building, we can literally see an effective stacking of styles as the cupola reaches far into the air.

As in Brooklyn, City Hall (completed in 1812) in lower Manhattan became a magnet for public architecture at the start of the twentieth century, as the newly incorporated city of Greater New York needed more civic buildings to accommodate its expanding bureaucracy and judiciary. The Manhattan Municipal Building and the judicial buildings of Foley Square, located just to the east and north, respectively, of Manhattan’s City Hall, used classical forms to make a de facto civic center. The creation of this civic center embodied the values of the City Beautiful movement and has parallels in San Francisco and Cleveland.47 The Manhattan Municipal Building (1907–1914), rechristened in honor of New York’s only African American mayor, David N. Dinkins, is an imposing classical skyscraper designed by McKim, Mead & White, which was strongly based on the skyscraper that the firm had proposed for its failed bid to design Grand Central Terminal.

FIGURE 18. Temple of Venus, Baalbek, Lebanon, 1905.

Source: The Library of Congress.

The classical elements are concentrated at the ground level and at the very top, where its imposing crown and Adolph Weinman’s sculpture Civic Fame form a recognizable element of lower Manhattan’s skyline (Figure 19). The west-facing ground-level façade is composed of a screen of columns, at the center of which appears to be a Roman arch (with a main bay and two smaller flanking bays), clearly evoking the Arch of Constantine (Figures 20–21).48 The arch is really a free-standing colonnade, also partly modeled on Bernini’s colonnade at St. Peter’s in Rome,49 like the Manhattan Bridge’s colonnade. The arch is an ingenious solution to bridge Chamber Street and provides a grand approach to the building. Above the central bay, in the architrave, two winged cupids hold a tabula ansata (Latin for a table with handles) inscribed with the word “MANHATTAN.” Inscriptions—“NEW AMSTERDAM MDCXXV” and “NEW YORK MDCLXIV”—also grace the architrave and affirm Manhattan’s position at the heart of New York since the city’s inception. Shields, which symbolize New Amsterdam and the English province of New York, as well as the city, the county, and the state of New York,50 stand in place of the captive Dacians on the colonnade’s architrave. The shields also are replicated on the faux-Corinthian colonnade above the twenty-second floor.

FIGURE 19. Manhattan Municipal Building with Civic Fame, Manhattan, historic postcard, early twentieth century.

Source: Author’s collection.

FIGURE 20. Colonnade, Manhattan Municipal Building, Manhattan, 2020.

Source: Author.

FIGURE 21. Arch of Constantine, Rome, 2016.

Source: S. Zucker (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Nestled in the arch’s north and south spandrels are female and male winged victories, respectively. Over the small bays, the roundels, also designed by Weinman, evoke the tondi on the Arch of Constantine. In the north roundel is Civic Duty, while in the south is Civic Pride, both female personifications. In the base relief, Civic Pride receives tribute from her citizens. Just as the shields and Corinthian colonnades provide visual unity at the building’s entrance and top, Civic Duty and Civic Pride complement Civic Fame, who stands atop the building.

Civic Fame stands on the pedestal, composed of a tall cylinder lined by columns, flanked by four smaller column-lined cylinders. The central cylinder clearly took its inspiration from the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates (Figure 22). A choregos, or patron of musical performances in ancient Greece, Lysicrates had erected a monument in Athens to celebrate the first prize winner in a musical competition he had sponsored in 335/4 BCE. Having been published in The Antiquities of Athens, the monument was widely reproduced first in Europe and then in the United States.51 In lieu of the monument’s original Corinthian capital, Civic Fame stood tall, reminding New Yorkers to take pride in their city.

Turning immediately north from the Municipal Building, one reached Foley Square, where again one might be forgiven for thinking that one was in a Roman forum or Greek agora, as the space was partially lined by colonnaded courthouses. Drawing on the ideals of the City Beautiful movement, Mayor George McAneny wanted Foley Square to serve as a location for a new civic center.52 While McAneny’s vision for a civic center was scaled back, the built elements speak to the staying power of classical forms. At the heart of this complex was to be the New York County Supreme Court, which was modeled on the Colosseum, Rome’s famed amphitheater.53 While it was transformed into a hexagonal building, it retained its classical façade, with a well-decorated pediment supported by ten Corinthian columns. Directly to its south is the United States Courthouse (1933–1936), also known as the Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse (Figure 23). Designed by Cass Gilbert and his son, its ground-level façade is dominated by a portico of ten four-story-high Corinthian columns.54 Its simple architrave, with the inscription “United States Court House,” is framed by vegetal scrolls at the north and south ends. Above this is a series of windows and the busts of four ancient lawgivers, Plato, Aristotle, Demosthenes, and Moses, who are framed in roundels, giving them the appearance of ancient coins. They seem to gaze down upon the jurors, lawyers, and judges serving and working within, reminding them to do their duty and uphold the law, as these men had done.

Set back from the colonnade, a 590-foot tower reaches into the sky. The tower closely resembles St. Mark’s Campanile in Venice, one of the most recognizable buildings in the canon of Western architecture. Its tall, thin proportions made it eminently suitable for a skyscraper. The top, however, returns to the classical world for its inspiration, drawing on Vitruvius’s and Pliny the Elder’s descriptions of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus as well as on Renaissance reconstructions of the famed site, one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world.55 This building’s eclectic elements—the colonnade façade with inscriptions and busts on ground level, the campanile-like shaft that gives the building its height, and its top modeled on the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus—reflect the movement toward a more eclectic use of classical forms, so typical of Neo-Antique buildings, that occurred in the mid-to-late nineteenth century and throughout the early twentieth century.

FIGURE 22. Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, Athens, 2019.

Source: Author.

FIGURE 23. US District Court for the Southern District of New York and US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, now the Thurgood Marshall United States Court House, Manhattan, c. 1936.

Source: The National Archives.

The Manhattan Municipal Building and Foley Square reflect the lasting influence of the 1893 Columbian Exposition on architecture, especially on public architecture. While Lewis Mumford and other critics railed against the gleaming white classical architecture of the Columbian Exposition,56 its effects cannot be understated. The Columbian Exposition’s classicizing buildings and the grand Court of Honor—with its triumphal arch, colonnades, and monumental statue of The Republic—led to a powerful reassertion of classical forms, especially those of imperial Rome, as the preferred modus operandi for public architecture (Figure 24). It led to a veritable explosion of plans for civic centers that used classical architecture in other cities, including San Francisco and Cleveland.57

FIGURE 24. Court of Honor, Columbian Exhibition, Chicago, 1893.

Source: The Boston Public Library (CC BY 2.0).