Читать книгу Tropical Living - Elizabeth V. Reyes - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

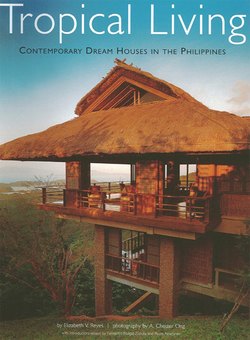

Оглавлениеa different tropical style

The Republic of the Philippines shares with Indonesia the distinction of being the largest tropical archipelagos in the world. It has 7,100 islands, which range from small coral atolls to huge islands with deep forests and towering volcanoes. Wherever one travels in this beguiling land, there is always the promise of a breezy tropical scene; and there is always a new beach, with swaying palm trees and clear blue skies, where warm waves break and slide over the sands.

In tune with the country and climate is a relaxed, contemporary architectural style. Homes are tropical, exotic, romantic; there is a prodigious use of light and space; breezes flow through rooms, cooling and caressing occupants. A permanent feature is the lanai, a type of verandah that has wide eaves to shelter the interior from the sun and is open to the elements on at least three sides, thus ensuring the free flow of cooling breezes. In many cases it acts as an alternative to the more formal dining room. It is the place to lounge in, to relax in, to take in the scents of a tropical garden.

Filipino house design also reflects other features of the environment, such as the sea or the forests. For centuries, the capiz shell, a bivalve flatter than the oyster and more translucent when cleaned, has been used as the tiny panes of traditional wooden grid-windows. In modern design, capiz shell finds new applications, such as in lightboxes, picture frames or as tear drops in chandeliers. Furthermore, people who can afford it furnish their houses with increasingly rare local hardwoods which are superior in density and texture; one such example is the nana, a fragrant wood with an intense sienna color. In recent decades, other woods from the foothills are being used. Examples include coconut and bamboo trunks which, when split, flattened, diced, and laminated, are transformed into classy boards with unexpected textures.

There are many varieties of house design in the Philippines. Consider the lanai. One common interpretation used in beach houses is a simple structure of bent wooden columns that draw the thatch roof and split-bamboo ceiling close to the ground. Just as popular is the Mediterranean variation: eaves of curved red tiles, plain stone pillars, and tiled floors. Or the starkly simple: a cantilevered,concrete roof and highly polished marble floor that together extend outward to meet the sky and the lawn. There are also the personal, one-of-a-kind interpretations, such as the lanai that marries stone columns with ornate capitals and lace-like metal tracery on the roof edge.

Variety likewise characterizes Filipino furniture. Bauhaus inspires the locally made, severely simple furniture in. stainless steel, vinyl and glass; or, lately, comfortable sofas that combine wood and abaca, an extremely versatile hemp fiber. Yet other furniture styles include Mediterranean-inspired designs with a lavish use of scrolls and iron as the predominant material. Others draw on influences closer to home and simplify the horseshoe-shaped back-and arm-rests and curving back slats of Chinese chairs. There are, of course, other,designs that cannot be readily pigeon-holed. One example is designer Ernest Santiago's highly personal and comfortable long chair that evokes a river bank. Formed from multiple materials—twisted driftwood for the backrest, river stones for support, and flat serrated driftwood for the seat, it is a highly individualistic piece.

Unfortunately, Filipino design is little known abroad. Despite the extensive use of English in the country, the Philippines seems to have received less publicity than its neighbors. But in an era that increasingly appreciates cultural fusions between East and West, the Philippines is set to play a unique role as one of the original fusion cultures. Filipinos belong to the Austronesian-speaking peoples who populated an island realm that extended from Madagascar to Southeast Asia to Polynesia. Their indigenous houses were frame constructions with raised floors, built near or over water. Thatched roofs were steeply pitched to facilitate the release of hot tropical air and to drain off heavy rain. Wooden columns dug deep into the ground supported the trusses (these columns sway during the frequent earthquakes). Timber or bamboo walls were merely screens to keep out sun and wind. Furnishings were sparse: a low table, chests, and, in the absence of beds and chairs, woven straw mats.

In the late 16th century, Spanish colonial influence introduced stone and tile. However, earthquake conditions compelled builders to develop a "mixed style" (arquitectura mestiza), where solid wooden pillars of native tradition were implanted in curtain walls of stone or brick, thus defining room spaces. The upper-story walls of these new Filipino houses were made of wood and had large window openings with sliding panels of translucent capiz shell panes in checkerboard pattern. They recalled Japanese shoji screens, for along with the Chinese came Japanese settlers. The wood-and-stone Filipino house marries continents.

Other influences are evident. Seventeenth-century Manila was the anchor of the galleon trade, the first global commercial network to link three continents. Island-made galleons brought precious Oriental goods to Mexico, which then shipped them on to the Americas and Europe. In exchange, highly prized Mexican silver entered the Orient and enabled Filipinos to construct grand houses that bridged East and West. Tables, chairs, and commodes, inspired by European styles but in island hardwood, appeared. Decor was eclectic: saints carved from lndian ivories, Chinese lacquered screens, and Persian carpets, for example, may have been displayed in one room.

Modern building technology appeared in the twilight years of Spanish rule and became widespread after the U.S. took over in 1898. Public buildings, offices, and residences built in reinforced concrete in modernist styles, from Art Deco to the International, appeared. Although many buildings were destroyed during the Japanese Occupation of 1942-1945, after 1946 reconstruction following independence encouraged experimentation with modernist styles. Schools teaching contemporary design opened.

Some observations can be made about modernism in the Philippines. First, the partnership between the ubiquitous thatch and bent wooden columns continues to inspire architects who love the seemingly "natural." Second, the presence of both massive stonework (in the ground floor) and light woodwork (in the upper story) illustrates the way in which Filipino architects are attracted to experimentation with voluminous shapes as well as lean, linear forms. Third, the fact that the houses bring stylistic traditions together encourages Filipinos today to explore different architectural traditions. They feel equally at home with the stucco arches of the Mediterranean, as they do among the steeply-pitched hipped roofs, wide eaves, lavish woodwork, and translucent windows of East Asia. A discriminating cosmopolitanism characterizes the best of today's Filipino design.

One major stream of "modern" architecture, the so-called "Prairie Style" of Frank Lloyd Wright, acclimatizes well because there are many parallels with local traditions. The Prairie Style integrates a building with its landscape. Horizontal planes and organic-looking materials—such as irregularly shaped stones and wood with articulated grain— are paramount. Reinforced concrete allows openings to extend along most of a wall's length and even turn corners without endangering the structure. Floor plans are asymmetrical and less formal; partitions between rooms are minimal; house interior and exterior landscapes flow into each other. This style echoes many elements in traditional Filipino architecture: house parts in the provinces are often textured, and the irregular bent of wooden pillars is celebrated. The frame construction permits large openings and even corner windows. The huge roof and the long windows spread horizontally. Even so, the Prairie Style is novel in its use of the relaxed asymmetrical floor plan and embedded metal framework.

Sometimes it seems that designs of modern Philippine houses seem too close to Wright, but in reality such new styles have enabled Filipino architects to explore possibilities latent in their own tradition. For instance, one of the most famous of Filipino architects, Pablo Antonio Sr., built his family house in the 1950s with a long, low window that turns a corner in his expansive living room. This may allude to Wright, but it also takes its influence from traditional Filipino style. Antonio adds a novel touch: the window becomes a cozy seat, shaded by generous roof eaves that rest on articulated diagonal struts.

The other influence in modern architecture is the "International Style." Inspired by industrialism, it pares down design to its essentials, as in a machine; it proposes that the building should express its intended function. Thus, a house must look like a house, an office like an office; unnecessary surface ornamentation is discouraged. The International Style philosophy states that beauty resides in articulating, honestly and simply, the function of each part, such as the stairs or the doorknob; and that the materials themselves—polished marble, wood, or metal—are in themselves attractive. To emphasize its break with the past, its proponents flatten the roof.

Ultimately, however, Filipinos love a homey look: they do not see a house as a home if the roof is flat, so the International Style has become more popular for office buildings and furniture than for dwellings. Still, some architects like Ed Calma elicit poetry from function. The brick-and-glass house he designed for his uncle, Pablo Calma, opens like a Japanese fan around a bamboo thicket in an inner courtyard. There are levels and sub-levels. Some levels open into rooms, others into a series of open-air terraces.

The second half of the 20th century saw the emergence of a more contemporary Filipino style. Architects reinterpreted local materials in new and exciting ways. Gray volcanic rock (adobe), abundant around Manila, appeared as cladding for walls; capiz shell panes in different patterns were used for various decorative elements; rattan, coconut lumber, and fiber textiles took on new life in paneling. Architects responded to the high humidity and monsoon rains of the tropics with designs that included steeply pitched roofs, high ceilings, minimal wall surfaces, and luxuriant gardens with cooling pools.

At the same time, Filipinos continue to enjoy reinterpreting regional styles. One favorite is the Mediterranean, with its roofs of curved tiles, cheerful stucco walls, iron grilles, and decorated tiles. Another is the Japanese: Sliding shoji screens, that may have inspired the ancient sliding shell lattice windows Filipinos grew up with, have returned. Then there are those tiny gardens that bring the outdoors into a Japanese-style interior. And the thick mats for sitting or sleeping on that recall the Filipino's own habits. Lately, a style that borrows elements of Balinese architecture has become popular. Pavilions, with square stone columns and hipped thatch roofs emerging from limpid pools, now appear in private gardens; and holiday homes in lumbung or rice granary form and shape are not uncommon.

Postmodernist Style has not been totally ignored either. Postmodernism began as a critique of the International Style's supposed indifference to ornament and context. But since the fascination with historic styles never died out locally—even during the International Style's high noon in the '50s-'80s—local architects have easily adopted, without apology, some postmodernist traits, such as the casual reinterpretation of previous styles.

Other Filipino houses are extremely personal statements. Their owners are not trained architects but simply people who have decided to design their own abodes. They literally dirty their hands with cement and paint, creating designs as they go along. They may rescue worn-out banisters, paint them in vivid colors, and install them on a brick wall decorated with broken pieces of glass and porcelain. Thanks to their keen sense of style, potential kitsch becomes delightful bricolage. Their one-of-a-kind houses reflect the Filipino culture's tolerance for the unconventional.

In this book, we showcase contemporary tropical style in the Philippines in all its manifestations. Variety is key: in reflecting the country's multifarious traditions and the diversity of its individuals, the houses featured are all fascinating examples of Filipino ingenuity and imagination: Enjoy.