Читать книгу Tropical Living - Elizabeth V. Reyes - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеasian fusions & cross currents

There is a growing body of Philippine architecture that is defined by the opening up of buildings to more light and air, an appreciation of natural indigenous materials, and the use of tropical craft techniques and Asian embellishment—all designed to reflect the "modern" Filipino lifestyle. This "fusion-style" probably began to manifest itself in the late 1960s when a nationalist movement in culture and the arts influenced architecture: Spanish-era colonial buildings were re-discovered and restored. Also at this time, orientalism of a local kind cropped up in the revival of interest in Philippine motifs (specifically from the Islamic regions of the country). The result was a type of Creole architecture that combined an inside/outside lifestyle with living areas connected to gardens by a lanai (a term of Hawalian origin), terrace, or verandah (depending on the overall motif: Spanish Mediterranean or California-sprawl).

In the 1980s, affluent Filipinos discovered the pleasures of traveling within Southeast Asia. Thailand became a much-visited destination and Baan Thai motifs started to appear in Philinppine homes as a form of interior embellishment. Bali then became popular, and a "Bali-esque" or "Baan-esque" style emerged in Filipino houses, initially replicating Balinese courtyards and gardens, then eventually the pavilion design of resorts in both Thailand and Bali Wood was layered over concrete, tile over metal roof, and natural textures over smooth machined finishes. The outside was invited in and the ubiquitous Balinese or Thai garden lamp replaced the Japanese stone garden lamp of the '60s. Parallel to these developments, architects such as the Manosa brothers and Gabby Formoso continued to develop an indigenous style That style sought to go beyond the superficial use of native materials (even though their experiments with coconut and local woods were commendable in themselves) to create a particularly Filipino style that made extensive use of light and space.

This emerging genre is still defining itself. Most of the newer generation of Filipino architects have either come from extensive work or study stints overseas. They are absorbing and integrating many of the pervading international trends into their still-evolving worK in the Philippines. Houses appear lighter and airier; there is a greater use of natural local materials, such as native slates, limestone, and sand stone: and there is more variety in the textures of wood, bamboo in-finishes, and embellishment. Finally, there is a rediscovery of craft techniques in wood joinery and stonework that traces its development to the first millennium buildings in these islands.

All of these tropical-style elements are brought together in a design program that reflects the "modern" Filipino lifestyle: one that is a product of a globalized, even westernized outlook, yet is increasingly appreciative of its deep cultural roots and the richness of its design heritage. It is an evolving style with a thousand years of tradition.

——by Paulo Alcazaren

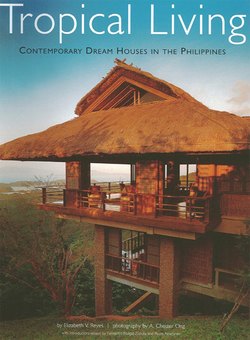

Jaime Zobel Hilltop Guesthouse

hilltop eyrie in mindoro

Puerto Galera, Mindoro, is a laid-back beach resort off the southern coast of Luzon. The town has an ever increasing number of resorts, diving operators, expat residents, and folk-art collectors of Mangyan weavings and crafts. To the far east of the resort areas are Jaime and Bea Zobel's two guest houses, designed by architect Noel Saratan. Don Jaime Zobel de Ayala, industrialist-developer, civic leader, and diplomat, arts-patron and art-photographer, specified "something very rustic, using local materials only" for these two hybrid houses. Both draw on Japanese inspiration and proportions, and make extensive use of capiz shell, green slate stone, and cogon grass for thick roof thatching.

In 1996 Saratan conjured a unique hilltop aerie with a spiral staircase leading to a Zen garden. Set within the confines of the Ponderosa Golf Course above Puerto Galera, this 160-sq-m masterwork was inspired by Japanese Zen gardens. Buffeted by the wind at 400 meters above sea level, it has spectacular views in three directions (see right). Set on a 2,000-sq-m plot, but on a 45-degree slope, it is essentially a two-story babay kubo standing nimbly on four-story concrete piling posts sunk two meters into the slope. Cubic in shape, it is topped by a thick cogon roof. Its most celebrated feature is the magnificent stone staircase that spirals down (two circles) to a white-pebbled Zen garden at the base. One crosses to the house itself over a bridge posted with six thick yakal trunks. Inside, bamboo pole ceilings hover above walls clad in woven bamboo, and black and brown Mangyan nito vine weavings. Japanese slatted wooden screens and Philippine latticed windows of capiz shell add to the overall textural symmetry. The linear aesthetic is Japanese, while the earth-brown tones are very Filipino.

The stunning stone staircase (left) spirals down to a white-pebbled Zen garden at the base; set with candles in the early evening, it takes on a magical air. The house walls (above and right) are clad in a skin of interwoven bamboo and the entrance resembles that of a Japanese temple; the structural posts are made from shale rock found in Mindoro. At the bottom of the spiral staircase is a granite water fountain (previous page) by Mexico-based Filipino artist Eduardo Olbes.

Inside (left and below), Saratan's eyrie house impresses with its thoroughly native Philippine symphony of rustic materials. Walls and windows are covered with black and brown nito vine-woven panels, made by the Mangyan tribespeople of Mindoro. The vaulted ceiling is clad with bamboo poles and pebble-washed concrete. There are slatted wooden screens and Philippine capiz shell windows on all sides.

Jaime Zobel Beachside Guesthouse

beachside guesthouse in mindoro

Three years after Don Jaime Zobel's hilltop house was completed, the Open House guesthouse was brought into being. Set back from the beach front, it is approached by a long wood-plank bridge (above) that crosses a stream dredged for aesthetic purposes. At the end of the bridge rises a pyramid-shaped staircase, with steps on three sides clad with fine slate stone chips. More wooden steps bring the guest into a proscenium-like verandah which adjoins several picturesque bedrooms.

The overall feeling in the architectural details is Japanese. Roof-to-ground posts line all four corners, and outer wall panels of capiz shell and wood trellises that swing open are reminiscent of shoji screens. On the other hand, the interiors which were designed by Johnny Ramirez have a distinctly vernacular Filipino touch. Plant-life murals cover the walls, giving the house a feeling of rusticity and fecundity. The piece-de-resistance is a six-paneled mural of Mindoro plant life by Emmanuel L. Cordova, while on either side of the sala are two bedrooms with heirloom bedsteads. There are four bedrooms in all. each tastefully furnished for weekend guests.

The guesthouse's airy verandah (above) features the six Mindoro palm murals by Emmanuel L. Cordova, as a background setting to plentiful butakas (traditional, long-armed plantation chairs). The petite escritoryo or traditional writing desk (right) is paired with an unusual seagrass-upholstered armchair designed in Cebu and a wastebin woven of nito vine by the neighboring Mangyan tribes of Mindoro. On either side, folding panels of wood-and-capiz can be drawn across to provide privacy for the ad joining bedrooms, two of which have heirloom bedsteads: one is an exquisite art-deco "rose" bedstead carved by the sculptor Tampinco in the 1920s; the other (above right) a wide kamagmtg four-poster of American-Shaker style. A third bedroom (far right) in quiet blue-and white faux-Japanese style has Philippine abaca wallpaper and shades.

Escaño House

tropical rustic

Designer Budji Layug declares that this clay-colored house with dark slate-tiled roof is in "Asian-tropicale style—always tropicale with an 'e'!" and it certainly fuses many elements. His brief was to take the half-finished house-structure and reorient and redesign the architecture and layout. Firstly he either removed walls or pierced picture-windows into them, generally decompartmentalizing the spaces to let in the light. Then he covered all interior surfaces in smooth, matte-clay tones—to give a feeling of modernity. And lastly, he added the garden: using roughly hewn railway ties and old Cambodian carvings, plus a rustic-Japanese style gate The result is an all-Asian composition.

The main house approach is clean and modern. Enter the wide door on its asymmetrical pivot, and you are greeted by a reproduction of an Ifugao pukok granary, now a reception table. Inside, the space soars to the two-story ceiling, giving the scale and proportion of a much larger house, complete with large glass picture windows high above eye level. A few steps further, and you start to focus on the furnishings and artworks: the sala centerpiece is a giant painting by Ben Cabrera, a landmark painter of women in dramatic, swirling robes; it is complemented by large sofas and armchairs covered in sica, the inner core of rattan, and touched with ethnic, earthy tropical colors.

Beyond a set of sliding glass doors, is the back lanai covered in sleek modern buff tiles. It connects well with the Japanese-style garden. Here, plants have been carefully chosen to provide a mottled shade, cut glare, and soften the modern textures. There is also a guest wing and the entire house is surrounded by a fence of wood molave railway ties.

The sleek wooden door (above) turns on an asymmetrical pivot, as one enters what feels like a modern Mexico setting on smooth buff riles. Everywhere in the Escaño abode one feels Budji's designer touch on the furnishings. (Opposite, clockwise from top left): The back patio is furnished with contemporary armchairs woven of fine rattan sica and mixed with Filipino rural furniture. The white-pebbled garden at the front makes a modern Japanese statement with with its dark trellised gate and modernist stone bench. In the bedrooms, comfy occasional chairs have subtle Oriental forms and textures; the guestroom carries the modern rustic theme with deep earth-colors and ethnic tribal weaves from India and Indonesia. The back lanai is a medley of ethnic weaves and fabrics.

Bencab's giant modernist painting of two kimonoed women in the high ceilinged sala (left). Earthy browns, sepia, and rust tones are echoed in all Budji's tropical furnishings creating a strong pan-Asian statement. The dining area (above) makes an impact like a modern art gallery, guarded on either side by primitive tribal artwork from disparate mountains—Mari Escaño's prized African sculptured figure at left, and a dark-wood bulol (rice-god figure) chair at right. (A Fernando Zobel abstract hangs 1 the light above.) The oval dining table is the longest single-pieco nara table in this book Above it hangs an Oriental domed landscape by national artist Arturo Luz.

Miñana hlouse

colonial processional

When architect Manny Miñana had the chance to build a 500-sq-m house to his own dreams and inspirations, he integrated a clean American sensibility with Asian tropical sensitivity. As a conceptual whole, this Ayala Alabang abode reminds one of the Oriental Hotel in Bangkok—all clean and pristine white, with giant trees dominating the space and groupings of rattan furniture among the collonades. Says Miñana: "This is a simple, elemental, conceptual home; an all-white, tropical, contemporary house on the outside, with no moldings and embellishments, and lots of garden." Using a vocabulary learned from Miñana's three Filipino mentors—architects Leandro Locsin, Gabby Formoso, and Bobby Manosa—the house has the feeling of space that dominates the work of Sri Lankan maestro Geoffrey Bawa.

The white bungalow has a "three-layered approach" that culminates with the inner, private quarters. One is drawn inwards seamlessly, entering the front yard and stepping up into an open corridor of white columns, where the orientation is immediately focused down the hallway toward an objet d art: an excavated, antique jar on a pedestal. Between the columns is the outer lanai, set beneath large skylights. This front courtyard is an indoor-outdoor setting of rattan chairs, lush plants, antique furnishings, and a distinctly languid tropical air. Here one senses the passage of time as the light changes through the day—from a creamy glow in the early morning to a deep violet hue at night.

Adjacent to the outer lanai and through wood and glass doors is the elegant, modern sala. From the sitting area in this room there are views of the invisible-edged swimming pool and the lush side garden. At the other end of the room, the sala naturally flows onto the family room, which has another vista of pocket garden as backdrop to the arrangement of daybeds and lounging pillows from Thailand.

(Previous pages) One enters the clean contemporary Alabang house through a colonnade of modern white columns: and steps into the adjacent front lanai—a lush indoor-outdoor setting. "The changing light freely entering the space gives spirit to the house," says architect Miñana.

Denise Weldon, Minana's photographer wife, orchestrates the gracious interiors. The main sala (opposite) is a well appointed room with wide floorboards of yellow narra, a spirited mix of contemporary and heritage furnishings, and walls of modern art. The long dining room (above) houses a large tropical tree; Lanelle Abueva stone-ware table setting; lush flower arrangements by Mabolo; and an eyecatching monochrome artwork by painter Arturo Luz. Weldon's rustic eclectic artifacts grace the pictorial: a cornhusk lamp by Mitos Cooper of Bacolod (left) and a black Ifugao rice measure, now a vase for fresh white roses.

Fernando Zobel House

pan-asian pavilions

"I like to layer the spatial experience of my houses," says Andy Locsin, son, of the famous architect Leandro, and, to prove the point, he explains the layers in a house he recently designed for Fernando and Catherine Zobel. The fist layer is an all-white one-story blank concrete wall that accosts the visitor and draws him under a tiled canopy to the front door. Past this is the second layer: two cooling pools of differing lengths, open on both sides of the foyer. Inside is the third layer—a vestibule that leads to three pavilions housing a dining room, a living room, and a lanai. These are colonnaded, and because they are adjoined by two pools, they appear to float. From the lanai, the visitor discovers another layer: to the side of the lot rises another two-story building that houses the private quarters. This building is connected to the living room by a corridor.

The roofs are steeply pitched and covered in flat, dark gray terracotta tiles made in Pampanga province. They rest on concrete pillars wrapped with reddish-brown narra. Because the gutter runs across the roof, rather than on its bottom edge, to discharge water into pillar-concealed pipes, the roofline juts in a knife-sharp profile. A pleasant contrast is the off-white sandstone paving.

The house has many Southeast Asian connotations: Recessed triangular arches frame the front door, as in Thai temples (left). The open-colonnaded pavilions, linked together by a central courtyard, echo Balinese palace design. In the middle is a huge, almost-black Indonesian jar. The series of V-shapes formed by the exposed rafters alludes to much of the region's vernacular house ceilings. The two-story private quarters are of whitewashed concrete; their sole ornamentation are narra panels that extend across the upper story's lower half and envelop the articulated pillars. The contrast between the stark white and the dark roof suggests a Japanese element, but the exposed pillars recall some 19th-century Batangas townhouses that articulate their wooden support-pillars before their cantilevered facades. The postmodernist Locsin cays he "permutates" rather than copies elements of admired styles, and, in this house at least, variations on triangular shapes pull the allusions together.

(Previous pages) Multiple layers and levels of transparency and privacy are expressed in this aesthetic composition of wood and glass. Roof profiles and proportions allude to Japanese design, while long, processional corridors are reminiscent of Thailand, Patrician homeowner Fernando Zobel, a "frustrated architect," was intensely involved in the entire design and would have no less for his elegant pan-Asian home.

The project comprises three glass-lined pavilions arrayed separately but serenely amid the expansive Makati property. By night the jewelbox pavilions seem to float on the swimming pool waters. The architectural elements are unified within and by the water: a clear canal surrounds the house by the front door; a reed pond by the edge of the dining room; and the swimming pool that comes to the very edge of the formal sala.

Ho House

modernist orientations

Despite its minimalist western framework of flat roofs and white polychromy, the residence of Doris Magsaysay-Ho is a tropical courtyard house. Organized around an axial core of three progressively larger spaces, the central courtyard is the focal point from which all spaces radiate. Designed by architect Conrad Onglao, the large, five-bedroomed bungalow (a reworking of an older house) is a safe haven for its owner. The house is entered via a canopied threshold into a courtyard framed around a koi pool. Hints of the succeeding spaces are glimpsed through the Iimbs and foliage of a large pandanus tree and the textured bricolage of stone and wood figures This hinting of spaces and layers beyond reoccurs throughout the house—a spatial conversation hat pleasantly leads one into the house.

The central sanctum is a high-ceilinged living room that branches left and right into the bedroom wing and a dining pavilion. The spaces are liberally accented with pieces from an exquisite collection of Asian artifacts and the paintings of the owner's renowned artist-mother Anita. But the real core of the house is the next space, the central courtyard. Most social activity extends or is visually directed into this space A geometric pool lined with French limestone sets the stage for and reflects wonderful dinner parties, intimate soirees, or the morning scene of a poolside breakfast under the fauvist purples of bougainvillea blooms. In fact, all the spaces in the house have this connection between outside and inside.

Yin and Yang is mirrored in the contrast of the tropical textures of native hardwood, woven coverings, and cane of furniture against the white flat concrete and glass planes of the house. The palette of spaces Onglao uses allows his client and her guests settings with appropriate levels of sociability, privacy, and intimacy. The house's spaces are further framed by a lush landscape that soothes and calms rather that confines. This is the substance of the house, warmly reflecting the owner's persona and the designer's understanding of it'.

Interiors are elegant and Oriental with modern paintings by Anita Magsaysay-Ho, the owner's mother. Fine prints and paintings and cushioned furniture are enjoyed on the open-air terrace (left)—a non-traditional design notion introduced by LA-experienced designer Conrad Onglao.

(Previous pages): Oriental feng shui plays a spirited role in the design. In all directions there are multi sized water ponds and pools, set with requisite statuary. Out back, a grove of trees and gazebo honors Ganesh within the lush landscape by Ponce Veridiano. The visual focus is a sea-green swimming pool in a courtyard with wide covered terraces looking in from rooms on three sides. Four tall centrally pivoting glass doors lead from one of these terraces into a square, higb-ceilinged sala. Here, the walls are clad with maplewood and pierced with skylights and picture windows on all sides.

Makapugay Compound

a fusior of styles

The exotic weekend retreat of the Makapugay family is called Casal da Feiticeira or Enchanted Castle. Located on a high spot on the Calatagan highway, the resthouse overlooks the shimmering China Sea and celebrates a fusion of styles: Balinese, colonial Indochine, and certain Portuguese elements. Comprising four cogon-thatched units of differing sizes, all hunched around a dark, stone-lined swimming pool, it has two bedroom suites, a sala and dining pavilion, and separate kitchen unit all interconnected by wooden walkways raised three steps off the hot Batangas ground.

The compound was designed by Jun Makapugay, Raul Manzano, and Becky Macapugay Oliveira and is a celebration of rustic-chic architecture combined with stylish interiors. Overlooking the left side of the pool (overleaf) is the wide-open dining room, connected to the sala by a brief passage through a Zen garden of white pebbles, crowned by a Thai bodhisattva. The sala combines an eclectic mix of traditional Indonesian furniture, while the guest bathroom is an amazing work of shell craftsmanship: thousands of sigay (small cowry shells) line the walls and light spills out of giant volutes.

The bedroom pavilions express the tastes of the two separate owners: Manzano stays in a headman's octagonal-shaped loft, while Becky Oliviera, the much-traveled mistress of this picturesque Asian beach manor, stays in the lovely Indochine suite. Every inch speaks of an elegant colonial-chic taste.

(Previous pages) All is Asian, elegant, and eclectic in the main pavilion The dining room with a balcony over the pool connects to a contemporary Asian sitting room, passing through an oriental "altar" setting: a Zen garden of white pebbles and a Thai bodhisattva blessing all who pass there. The sala (above) is an exquisite Pan-Asian mix of traditional Indonesian furniture with contemporary Western armchairs, antique oriental statuary and accessories with modem Arrakis Oggetti lights suspended overhead truly an avant-garde accent.

Bedroom interiors express tastes of separate but equally stylish co-owners: For bachelor Manzano, the octagonal headman's loft, a two-story Asian-Javanese unit with masks and spears at the door (opposite, top), complete with four poster bed with Chinese carved headboard; and day beds and games to play upstairs. For Becky Oliviera, a pure Indochine setting: her four poster bed, custom-made by E. Murio in fine cane, is draped with gauzy curtains, matched with twin black drawer sets and an antique cabinet from the ancestral home.

Yabut Compound

bali-mexican fantasy

Situated in Calatagan on the southernmost tip of Batangas province, the weekend home of former Manila Mayor Nemesio Yabut is part-tropical resthouse pavilion and part-southwestern ranch Built atop a commanding hill, the house glows from a distance: it is newly painted in bright shades of papaya, aqua, and raspberry: refurbished with nipa roofing over a massive fro t verandah; and lit up with hot-colored throw pillows and covers, ceramic jars, and massive modern accents. The interior designer daughter, Gayle Yabut, upkeeps and updates what she calls the family's "modern Filipino-Mediterranean" vacation house (right and page 52). Her own house (see pages 56-59) and the house of her brother (pages 53-55) lie close by—the three dwellings comprise a fanciful fusion of Balinese, Mexican,, and African architecture.

On a separate hilltop. of the Yabut property is an outre and off-the-wall creation, designed by Nemesio Yabut's son, Ricky This weekend abode started from a simple pueblo-style bungalow—with organic, rounded wall edges, and rustic wood inserts—and blossomed into a multicolored New Mexican fantasy. From the outside, the house gleams with the bright shades of the main Yabut house—Ricky paints his place in ripe papaya, fuschia-rose, and dijon-mustard, hot fiesta colors that seem to have spilled over to his own hilltop. His longspan rooftop is tinted bronze; his floors are of varnished, polished cement. And all around are the graphic plants that can take the hot Batangas sun: yuccas, sugar palms, and cacti.