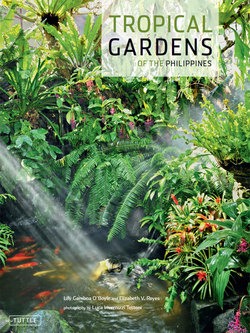

Читать книгу Tropical Gardens of the Philippines - Elizabeth Reyes - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE PHILIPPINE TROPICAL GARDEN

The Philippines—from rice terraces that climb to the heavens to little cottage plots found along the outskirts of towns combining orchard, vegetables and flowers—is one big garden. A varied topography, diverse tropical climate, cultural assimilation from outsiders, and an inate love of nature all contribute to the huge variety of gardens we find in the Philippines today.

The Philippines did not have royal palaces and water temples that in places like Bali and Thailand helped define a garden model. The early Filipinos believed that spirits called anitos animated the forests. They worshipped the spirits along with nature in forested groves. Plants were grown mainly for food and medicinal purposes.

Prior to Spanish colonization, there was no tradition of ornamental horticulture in the Philippines. A 17th century depiction of a Philippine garden from the book Our Islands And Their People cites palm, nipa, banana and fruit trees of the village as surrounding the house. “The rice fields are nearby, as are the streams and rivers where men can fish or sail and trade with the Chinese junks at sea.” It was only after the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century that gardens planted for viewing pleasure came into being. Along with a newfound affection for water, the Filipinos developed a fascination for the plants introduced by foreigners from Mexico and Spain. Flora de Filipinas, published in 1837 by priest and scientist Fray Manuel Blanco, documented the rich plant life of the Philippines and was lauded by botanists all over the world. By the 19th century, townhouses with gardens and courtyards featuring fountains and flat open terraces called azoteas where old-fashioned favorites were grown in pots became the norm.

The concepts and implementation of landscape design came much later with the arrival of the Americans who also brought with them a love of lawns and open spaces. The Japanese subsequently introduced their disciplined traditions of pruning and plantsmanship. Stories abound of Japanese spies working as gardeners in the Philippines before the outbreak of World War II.

So, what are the influences that have made their mark on today’s Philippine garden? Certainly, the formality of the Chinese and Japanese garden which the Filipinos somehow minimize and modernize at every turn with unexpected plant combinations; the Latin flamboyance of the Mediterranean garden which they fine-tune with a more selective plant palette; and the fertile and skilled tradition of Philippine plantsmanship that plays like a melodic refrain through their gardens. Today, a spirit of innovation and creativity is sweeping the gardening world.

The Philippine house and garden draw their vitality from the country’s rugged geography and diverse tropical climate. The balcony of the home of Ely Bautista and Bill Lewis overlooks the lush tropical vegetation of Meros and the surrounding Laguna countryside.

Orchids are among the favorites of tropical gardeners not only for their wide variety but also for their long lived blooms. Below is one of many Dendrobium hybrids and at bottom is a yellow-orange Staurochilus loheriana sp. This small to medium sized monopodial species is endemic to the Philippines on the island of Luzon.

A contemporary country house with a huge garden designed by Noel Saratan was inspired by Philippine traditional architecture. A mural by Emmanuel Cordova depicts some of the country’s diverse plant life that can be found on the property.

A renewed interest in modern architecture has seen a similar interest in the garden. The garden is becoming a laboratory where new materials, plants and local artifacts can connect with the Philippine design heritage to create fun and livable contemporary spaces that exude a type of tropical modern vibe. There is the “high style” of the contemporary Philippine country house and garden, the “new style” look of the modern, chic suburban garden in and around Manila, as well as the “exotic style” of the romantic garden where the Filipino is at his best. Along with this comes a new breed of landscape designer and gardener, all trying to define a Philippine gardening style that is truly unique.

Jerry Araos, perhaps best described as a “philosopher gardener,” has long been an exponent of the “enhanced nature” or nature-inspired movement that is steadily gaining ground in the USA and Europe to the advantage of wildlife and biodiversity. Like Piet Oudolf and other German proponents of the New Wave Movement, he has crafted his own earth-friendly approach to horticulture and landscape design. For more than 20 years he has been designing wild, naturalistic gardens that call for dynamic, ecological plantings that are wildlife-friendly and at the same time self-sustaining without pesticides, complicated water systems and a large labor force. He is credited for redesigning the Manila Hotel gardens in time for the APEC Conference of 1997. A decade earlier, he had created a garden for himself and his family in a swampy piece of land in Antipolo. Today it is a tropical paradise where his poetic and sensitive interpretation of the garden form offers an inspiring and timely model for Philippine gardeners. Araos’ approach brings natural elements—earth, stone, water and plants—into a harmonious whole to convey personal philosophies about humanity and man’s relationship to nature.

The Philippines benefits from an extraordinary array of exotic and native plants available in the country. The sanggumay, Dendrobium anosmum, is one of 60 recorded orchid species in the Philippines.

Kapa kapa, Medinilla magnifica, is one of the most beautiful tropical epiphytic shrubs. Endemic to the Philippines, it is grown for its lush foliage and brightly colored flowers.

Mussaenda ‘Dona Luz’, an old-fashioned favorite named after one of the Philippine first ladies. This shrub is native to the Philippines.

The jade vine (Strongylodon macrobotrys), a native of the tropical forests of the Philippines, is marked by a deep blue-green color and has the texture of jade, hence its name.

Yuyung LaO’, a master landscape artist, is another name on the contemporary scene who has mentored many of the country’s young landscape designers. His innovative use of plants gives an international appeal to his landscape design, and also offers fresh ideas for how these plants can be used in a modern tropical landscape. The garden designer, Ponce Veridiano, is outstanding in creating tropical gardens. His career now extends into Sarawak, Hongkong and Brunei, but his breakthrough project was the Pearl Farm Resort in Samal Island, Davao. Here, he showcased his skill in combining the exuberant growth of native and introduced plants with an exacting attention to detail, texture, color and decorative accents. Recent work at his own home shows how his work continues to evolve.

The gardens of Jun Obrero, Toni Parsons and Bobby Gopiao, along with those of Rading Decepida and Jojo Lazaro, abound with a new naturalism. Proponents of the “nature managed” concept of gardening, their works exhibit an ecological sensitivity to the nuances of water, stone and vegetation. Outstanding tropical border designs tend to be composed of key plants, which are repeated through the garden to create rhythm and evoke the idea of plantings in the wild. To highlight the contrast between areas of strong light and deep shade, light-catching plants such as ferns and bamboo are used for their delicately textured leaves. Though naturalistic in feel, they become contemporary when combined with modern paving, and carefully maintained lawns. Sculpture and decorative objects are used around the garden to enhance and add interest while water is given special attention in the landscape.

The gardens of Ramon Antonio, Noel Saratan and Frank Borja all reflect an architect’s eye for space and a gardener’s passion for plants. A sculpted, spatial quality resonates throughout their work. Their modern tropical gardens are usually based on strong, clear structural lines, with winding, elegant curves in the ground plan and hardscapes, and a preference for bamboo and clipped boxed shrubs. Borja worked abroad for many years with the prestigious landscaping firm Belt Collins and has supervised many of the firm’s landscaping projects in the Philippines. His work, like Antonio’s, is designed not just to showcase plants but also to cater to clients’ leisure needs. This design trend, born out of functionalist and Modernist ideas of the 1920s, has been reinforced by gardening design shows and western makeover programs promoting the pleasures of water features such as pools and Jacuzzis, patios, barbecues and showy architectural plants in ornamental pots.

In Asia, where gardeners have traditionally been male, a number of women are now playing creative roles in the landscaping arena. Shirley Sanders, a self-taught landscape artist well known for her skillful and meticulous plantsmanship, is famous for designing huge resort-type gardens but she is equally adept with small spaces. Her modest-sized garden and nursery in the bucolic countryside of Los Banos, known for its mineral hot springs, is of particular note. Michelle Magsaysay, who designed the Alejandrino and Olbes gardens, has also established herself as a sought-after designer in the urban scene; she specializes in small-scale designs that combine an Asian formality with a contemporary slant.

Thanks to the now-famous vertical tropical landscapes of French botanist and artist Patrick Blanc, ornamental tropicals are the new darlings of the horticultural establishment. Many a visitor has stopped dead in his tracks at the sight of the hundreds of plants cascading down the walls of the Musée du Quai Branly and the Fondation Cartier in Paris. Taking their cue from this phenomenon, home-grown designers are also experimenting with tropical plants of varying leaf colors, sizes and patterns to transform contemporary architecture into living works of art. The extraordinary array of exotic and native plants available in the country today, as well as the advances in water filtration and irrigation, have benefitted the garden designer. New and hardier varieties of Anthuriums and Alocasias and more sun tolerant species of Philodendrons and Excoecaria cochinchinensis are enhancing many of the newer gardens, while excellent substitutes for yew and boxwood, much used in the west for hedges and topiary rounds, are found in Fukien tea, kamuning (Muraya paniculata) and Eugenia shrubs.

Creating a cool, sheltered area, which serves as an extension of the landscape is an integral part of the design of the tropical house. The home of Doris Ho is a union of indoor and outdoor living.

In general, gardens exhibit a wide variety of plant material mostly imported from neighboring Bangkok, Indonesia and Malaysia. The garden of Malyn and Ochie Santos in Lipa, Batangas is an outstanding example of a garden with a wide variety of introduced plants. Their amazing collection of unusual Philodendrons, Anthuriums and variegated palms showcased artfully by species is a horticulturist’s dream. While a notable few, such as Patis Tesoro and Cecilia Locsin, have made their mark with the combination of indigenous and imported species, others delight in combining the formal and informal gardening traditions of their Asian neighbors. Western models inspire others like Vicky Hererra: Her garden in the windy ethereal landscape of Tagaytay is particularly impressive with seemingly wild borders of perennials and annuals woven in delicate shifting tones.

Last but not least, there are those who showcase their artistry in stone in the great tradition of the Ifugaos, the Philippine mountain people who built the famous Banaue rice terraces. This engineering marvel, crafted of stone and water 2,000 years ago, covers an area of nearly 400 square kilometers (155 square miles) and reaches 1,500 meters (5,000 feet) in height in some places. Known for their skills as wall builders and stone craftsmen, many Ifugaos have been forced from their mountain homes to seek jobs elsewhere due to hard economic times. Their migration, unfortunate as it may be, has inadvertently made their skills available elsewhere to the benefit of the garden world. As a result, some of the most unique contemporary Philippine gardens excel in stone artistry.

Extensive and imaginative stone features, planted beds with sinuous edges and retaining walls, intricately constructed “rip-rap” walls, and more, are all commonly found in many of today’s gardens à la mode. Although stonework has been used in garden design since time immemorial, a high profile comeback has occurred recently in its practical and artistic uses. Though the essentials of construction remain the same, the sculptural qualities of the stone itself and the fluidity of design to which the techniques apply themselves are making dry-stone walling more relevant to contemporary as well as traditional gardens. The popularity of both garden walls and paving in modern gardens confirms the recent rise in demand for dry-stone work. Imaginative and influential designers such as Jerry Araos and Yuyung LaO’ and landscape artists such as Augusto Bigyan and Rading Decepida have recognized the potential of this ancient craft and have answered the call with highly pleasing sculptural, yet functional, creations.

The Cordillera wall of Jerry Araos in his Antipolo garden exhibits both mastery of and sensitivity to stone. He prefers to work with natural stone from Bulacan and Antipolo and creates many of his own designs relying on the old trusted techniques. Augusto Bigyan, on the other hand, specializes in exquisite stone and terracotta mosaics and uses a variety of stone materials in his walls and hardscapes. The stones in Bigyan’s projects vary widely depending upon the geographic location, but most are sourced from the provinces of Bulacan, Rizal and Mindoro. Escombro, a porous stone from Bulacan, is a favorite of many designers because of its ability to weather beautifully. The Andres’ garden waterfall, designed by Rading Decepida, is another example of how traditional garden features are being updated in sophisticated ways for the modern garden.

Clearly, there exists a myriad of different styles. During the three months we traveled around the country viewing and photographing gardens, we tried to showcase this variety, along with the wild enthusiasm of the country’s gardeners and designers. We wanted to get a sense of how the real Philippines connects with the garden and celebrate some of the best contemporary Philippine gardens. We hope that the gardens featured here will be an inspiration for gardeners, landscapers and garden designers in other parts of the world—those looking for something new, something borrowed, something true.

Lily Gamboa O’Boyle

Traditional stone features are being updated in sophisticated ways for the modern garden. White granite pavers cut horizontally and seamed with grass add a modern touch to this Thunbergia arbor designed by Jun Obrero for a Tagaytay client.