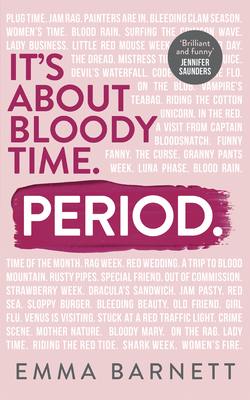

Читать книгу Period. - Emma Barnett - Страница 21

Bluntly put, often we put up with our internal lady piping and vaginas not quite working as they should because we are embarrassed and we don’t believe it to be our absolute right for everything to be more than all right.

ОглавлениеNor are we always believed by the doctors who listen to our woes – once we muster up the energy to try to communicate our problems.

I always knew something was wrong with me gynaecologically but I too soldiered on. From age eleven, these heavy painful periods were the norm. I tried everything – strong painkillers, drinking coffee (which I loathed but my mum had heard could help), furry hot water bottles, lying on my stomach, and then, as I grew older, getting just that little bit more drunk on nights out when I was either about to start or in full flow. And then at university, I finally found a pill which agreed with me (although not the large quantities of booze I was imbibing – I went from being an excellent loving drunk to quite the vile bitch drama queen). Hence began the great cover-up as I like to call it.

From the age of twenty-one to thirty, I happily chomped my way through pill packet after pill packet, and my periods, although still uncomfortable, became more manageable. But when my husband and I decided perhaps we should start thinking about having a baby and I ditched the pill, my real periods – the dark bastards – really started to return.

We couldn’t get pregnant. We seemed to have gone from a place of not wanting a baby urgently, to everyone around me falling pregnant. Suddenly I was in a place I’d always feared: infertility. Because somewhere deep down, I knew I wasn’t quite right, even though every doctor and specialist told me I merely had a bad case of dysmenorrhoea, a fancy word for painful periods. With a great sense of foreboding, I had secretly dreaded the stage of my life when I would attempt to produce life, convinced something might be wrong. And here I was. And it wasn’t going well. Far from it.

As each month went by during our two years of trying, my periods were getting worse. They were starting to reveal themselves in their full natural horror, free of the contraceptive mask which had been restraining them for the last decade. The lowest point I can remember on this knackering journey was during a holiday in Sweden, from whence my mother-in-law hails, walking behind her, my father-in-law and my husband, after a sunny coffee and cinnamon bun pit stop on a picnic bench. I felt like iron chains were dragging my stomach down, pulling me towards the floor, as my bones ground against each other during what should have been a lovely easy amble around a Stockholm park. I came to a complete stop, unable to take another step. I just couldn’t move anymore. The period pain was so great. I stumbled to the closest bench and didn’t move for a long, long time.

That was the moment I knew I needed some cold hard medicine. Not some muddy herbal tea nonsense from an overpriced acupuncturist. Nor another expensive and pointless colonic irrigation that did nothing other than to make me feel lightheaded and immediately crave a greasy cheese and caramelised onion toastie.

On that day, I admitted the first of two defeats. The first was that something was wrong with me to the extent that action was required. A week later I was booked in for a laparoscopy, a keyhole procedure which serves both as a diagnostic tool and a treatment for endometriosis. So, you sign off having a diagnosis and treatment while you are under anaesthetic, meaning you either wake up after a few minutes as no action was required or after a few hours as the doctor has been beavering away.

I was the latter. I did indeed have it, endometrium (old womb lining which should leave one’s body during a period), coating my organs, mainly my bowel and bladder, but very luckily it hadn’t stuck to my ovaries, uterus or fallopian tubes. The disease was at stage two of four. Moreover, after two and half hours of painful lasering (during which they inflate your organs with air) the doctor felt he had managed to remove all of it.

In the six months after a laparoscopy, women who have struggled to conceive naturally because of endo have a much higher chance of doing so. And the debilitating pain can go away or be significantly reduced. Sadly, despite our best efforts – and they really were Herculean – pregnancy still wasn’t happening and my periods were as punishing as ever.

Hence came my second defeat, as I stupidly and naively chose to view it at the time: I agreed to IVF. Not being able to fall pregnant felt like a huge failure. We’d been told repeatedly that our infertility was unexplained, so I had strongly resisted the idea of IVF previously because having such a major intervention felt like I really had failed and that we’d reached the end of the road.

An amazing older female doctor in the NHS promptly disabused me of this foolish opinion. She met with me and my husband for an appointment regarding our ongoing issues and my recovery following the removal of my endometriosis. All I really remember about this meeting with this wise, stern but kind doc, was her shiny grey ponytail and her saying something along the lines of: ‘For God’s sake Emma, stop being so stubborn and just have IVF. You’ve qualified for it on the NHS for a long time now, especially because you have endometriosis and have tried for more than two years to get pregnant. What have you got to lose? Your periods are awful each month and this is one way of trying to stop them and get pregnant before. It’s really a win-win situation.’

Before I knew it, despite all of my reservations about the hormones, the intervention, the hope, the potential crushing disappointment and the overarching feeling of total failure, I found myself saying yes.

The doctor sold the process to me on potentially ending my periods for a little while (that’s how bad they were) and I consented to the hormonal rollercoaster that is IVF without a millisecond of further contemplation. I didn’t for one moment dare to think it might work and produce a baby. No, that would be far too easy and require a dose of luck I didn’t seem to possess with my wrecked body.

I remember my husband saying: ‘Emma, wait. Shouldn’t we discuss this?’ As we were both bundled off for various blood samples, clutching consent papers. I turned back to him and simply replied: ‘No. I can’t go on like this.’ He went with it unquestioningly, because he’s a legend.

We had a big holiday already in the diary: three weeks travelling around China (another ‘we can’t get pregnant’ adventure holiday – where you splurge money on an amazing voyage in a bid to distract yourselves from the pain of unexplained infertility). Hero doctor agreed to wait until we came home. By this point, I was totally in her hands and meekly agreed to everything she said. It just felt so good to have someone else take control and bring some order to my menstrual and mental chaos, caused by not being able to conceive and not being able to exist easily in my pain-wracked body for one week every month.