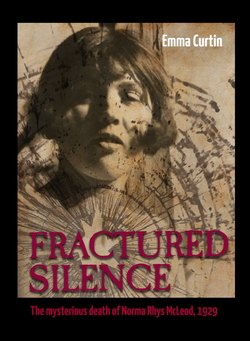

Читать книгу Fractured Silence - Emma Curtin - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

____________________

ОглавлениеIn that second week of September 1929, Norma McLeod was enjoying the school holidays, taking a break from her role as Kindergarten Teacher at Caulfield Grammar, a job she’d held for just two terms. Wanting to make the most of the vacation time, she’d planned a trip to Healesville by bus, to leave on Tuesday 10 September. She also took the opportunity to indulge in her growing love of golf. While only a beginner, Norma was apparently known to be keen on “out-door games”. Looking “younger than her years”, with a slight frame, her dark brown hair was kept in a short natural bob, in keeping with the style of the day and easy to manage for an active woman.

On that fateful Monday, September 9, Norma had allegedly lunched with her parents, 61 year old Edith, a housewife, and 63 year old Norman, a retired Defence Department staff clerk with the rank of Major. Norma’s brother, Rhys, aged 23, who also lived at home, was recorded as working that day at a furrier’s business in Elizabeth Street in the city.

According to testimony, the family chatted over the meal about Norma’s planned trip to Healesville and lunch finished at about 1pm. Norma helped her mother clean up the dishes while her father washed and changed ready to go into the city to help Rhys. Norman duly left, he said, sometime between 1.15pm and 1.30pm. Shortly after, Norma rang her cousin Edith Williams to organise a game of golf that afternoon. The McLeods had an ‘automatic’ telephone - number U.2703 - which meant that calls didn’t have to go through a switchboard operator. Only four percent of the Australian population in 1929 had a telephone, and few were automatic, suggesting that the McLeods liked to have the most up-to-date technology.

Cousin Edith Lloyd Williams was three-years older than Norma and a ‘ledger-keeper’ (a book-keeper). She was the daughter of Beatrice Williams, Edith McLeod’s younger sister. When Norma rang the Williams home, cousin Edith said that before she could commit to golf, she needed to “make arrangements” with her elder sister Beatrice, known as Trixie (perhaps to avoid being confused with her mother – the tradition of maintaining the same names throughout the family lineage certainly confused me, let alone the family). ‘Arrangements’ related to cousin Edith not having the appropriate shoes – presumably she needed to borrow some from her sister. Anyway, she said she would call Norma back to confirm.

Norma’s mother indicated to police that she had needed to do some shopping that afternoon at the local shops in Malvern Road, just around the corner from Mandeville Crescent. She apparently left home at around 2pm, leaving Norma ironing a blouse at the back of the house, ready for her golf game. Believing that Norma would have left before she herself returned, Edith asked her daughter to close the back door when she went out.

After visiting the butchers, Baines and Harts, Boston’s cake shop, Grinlington’s produce store and an Italian greengrocer, all on Malvern Road between Mathoura and Williams Roads, Edith said she returned home sometime around 2.30pm.

She was surprised to find the door still open. Entering the house, she called out “Norma are you still here?” When she got no response, Edith went to her daughter’s bedroom. On entering, she found Norma lying on her single bed apparently unconscious. Edith went to her own room and brought an eiderdown from her bed and placed it over Norma. She then went to get help.

Knowing that Mrs Madeline Guthrie, her widowed neighbour, had a companion who was a trained nurse, Edith hurried next door, saying as she was greeted, “Tell Miss Gwilliam to come quick I have found Norma on the bed unconscious”. Forty-four year old English migrant, Margaret Lillian Gwilliam, quickly obliged.

Miss Gwilliam told the police that, on entering Norma’s bedroom, she found the young woman lying on her bed with an eiderdown covering her, and a wet cloth (the underpants) covering her forehead and right eye. Norma was fully dressed, with the exception of her footwear – a pair of brown strap shoes – which were by the side of the bed. In the golfing fashion of the day, Norma was wearing a blue woollen pull-over with yellow bands, a cream silk blouse (the one she'd been ironing when her mother went out), a blue skirt, a white bodice with blue petticoat attached, a light blue woollen singlet, white flannelette bloomers, and silk stockings. According to her father, Norma was always “careful about her appearance”, presumably both in terms of neatness and fashion.

Miss Gwilliam wiped Norma’s face, removing a small quantity of yellow mucous and blood that was seeping from her mouth. That was the only mention of any blood. Miss Gwilliam told Edith to get the doctor. Norma’s mother ran to the family doctor’s surgery at 728 Malvern Road on the corner of Orrong Road, only moments away from her home. Here she found Dr Johnstone Simon Thwaites attending his patients. Telling him that he had to come as something was wrong with Norma, Edith was then advised to return home while Dr Thwaites finished with his latest appointment. He packed his medical bag and headed to Mandeville Road not long after Edith had left.

Sixty-four year old Dr Thwaites had been the McLeods’ doctor for about a decade, although he’d only been practicing from 728 Malvern Road for three of those years. He examined Norma and found her unconscious, with “no corneal reflex” (meaning Norma failed to blink involuntary when her eye was touched) and a slight linear mark on her right eyelid. She was breathing clearly with a pulse of 84 to the minute (within the normal range of 60 to 100 beats a minute). On Dr Thwaites’ advice, Miss Gwilliam took off Norma’s silk stockings and applied hot water bottles to her feet. When the pathologist later examined Norma, he noted that she was wearing “a blue woollen bed sock on one foot and a pink one on the other”. Presumably Miss Gwilliam had found whatever was accessible in the bedroom to keep Norma’s feet warm, once the effect of the hot water bottle had subsided, but that’s just a guess.

Dr Thwaites said he asked Mrs McLeod where her husband was. She replied that he’d gone to town but she didn’t know where he was. She thought he would probably be home around four or five o’clock. Dr Thwaites suggested that she try to find him and ask him to come home. Thwaites then left Mandeville Crescent so he could finish his surgery. At this time, Norma “appeared comfortable”. He returned at 3.15pm finding Norma’s condition unchanged. Leaving again soon after, Dr Thwaites wrote down his telephone number and told Mrs McLeod to “ring up at once if anything was troubling her”.

At 4.15pm, Thwaites’ medical partner, Dr John Reginald Davis received a phone message at the Malvern Road surgery. He wasn’t sure who made the call, but he thought it was probably Miss Williams, presumably Trixie Williams (sister to cousin Edith). In response to this call, Dr Davis headed to Mandeville Crescent. Aged 50, he lived on the medical practice premises in Malvern Road with Ida, his wife of almost twenty years.

On examination, Dr Davis found that Norma’s breathing was now “stertorous” (noisy and laboured), she still had no corneal reflex, and there was marked bulging of her right eye, which was quite black. Davis said he could feel a pond fracture (a shallow, round, depressed fracture) over her eye.

Just after Dr Davis’ arrival, Norman McLeod apparently returned from the city. He said “When I opened the door – I opened it with my latch-key – my wife met me and said in a very dazed manner ‘Oh daddy, something dreadful has occurred to our dear Norma. When I came home this afternoon I found her on the bed unconscious’”. Edith took Norman’s hat and led him into Norma’s bedroom, where he saw Dr Davis. Also in the room was Norma’s cousin Trixie Williams, as well as Dr James Perrins Major. Trixie was 34 years old and a trained nurse, a graduate of the Melbourne Hospital. Dr Major, or Jimmy to his friends, was well known to the McLeods and the Williams families. He’d been present at the death of Trixie’s sister, Octavia ‘Poppy’ Williams, in 1927 and had signed the death certificate. He would, four years after Norma’s death, marry Trixie Williams. It was perhaps Trixie who’d called Jimmy on that dreadful September day, maybe to seek his expert opinion, as well as his comfort.

Having both examined Norma, the two doctors, Major and Davis, conferred and apparently decided to do a lumbar puncture, now more commonly known as a spinal tap. This procedure had been introduced into the medical world in the 1890s and was developed in order to analyse the watery fluid (called cerebrospinal fluid) surrounding the spine, through which a number of diagnoses could be made. What they were expecting to find wasn’t reported.

However, while they were preparing to do this procedure, sadly, Norma died. It was approximately 5pm. Dr Davis rang Dr Thwaites and asked him to inform the police.

At some time between 5.30pm and 5.45pm, Constable Thomas Henry McDonald of the Toorak Police Station received a message from Dr Thwaites about the tragic death. According to newspaper accounts, the doctors had been “dissatisfied with the superficial examination” and refused to sign a death certificate, preferring that the body be taken to the morgue.

Constable McDonald, aged 40, had been in the police force for almost 19 years, working at the Toorak station in Springfield Avenue since 1924. He was known by his superiors as “efficient and well conducted” and, true to form, he took to the task in hand and set out to Mandeville Crescent (less than a ten-minute walk from the station) to follow up on the phone call. On arrival, he saw Norma’s body and made a brief examination of the house, finding that everything “appeared to be in order”. He noted that he heard “somebody in the front room crying and moaning” and was advised by Norman McLeod that this was the girl’s mother, who was “mad with grief”. Having completed his cursory review of the scene, around 6pm Constable McDonald accompanied Norma’s body to the morgue. The constable then contacted Senior Detective Arthur Lonsdale Lee, who, together with Detective Frank Unwin Simpson, went to Mandeville Crescent at 8pm that evening.

When they arrived, the detectives spoke with Norman McLeod. Mrs McLeod, however, was too upset to speak. Realising that little could be achieved at that point, the officers decided to return the following day.

Meanwhile, at 8.45pm, Dr John ‘Jock’ Rhys Williams was at the morgue positively identifying the body of Norma McLeod, his cousin. Thirty-six year old Jock was Beatrice’s eldest son and Trixie and Edith Williams’ brother. He lived with his wife Beryl, who was expecting their first child, in Glen Eira Road, St Kilda, a 10-minute drive from Mandeville Crescent.

Jock was the eldest child of Beatrice and John Lloyd Williams and, since his father’s death in 1926, he appeared to have easily adopted the role of patriarch. He was a slender man of 5ft 11 inches (about 180 centimetres), with blue eyes, dark short hair and an earnest face. The doctor was apparently “not unlike Noel Coward in appearance”, and was sometimes mistaken for him, much to his amusement. Other than a sketch of Norma in a newspaper, his face was the first family image I saw, downloaded from the internet.

Dr John ‘Jock’ Rhys Williams. Date unknown

A little ‘Googling’ and some research on the Ancestry website provided quite an impression of Jock. Educated at Wesley College, he’d graduated from the University of Melbourne medical school in 1915. A year later, as a 23 year old, he joined the Army Medical Corp with the rank of Captain, serving as a Medical Officer in France during the First World War. Here he demonstrated his generous and heroic spirit, saving the life of a young French girl whose siblings had been killed by a German bomb. Almost 80 years later, the grand-daughter of that little girl would write to John’s family to express her gratitude to ‘“saviour” Captain Jack’. On his return from the war, John became Registrar of the Melbourne Hospital in 1920. Eight years later, he was appointed to the diabetic clinic at the Hospital, probably the first specialist in this field in Melbourne. He was also a member of the British Medical Association (which was transformed into the Australian Medical Association in 1962).

Jock’s qualifications and character made him a force to be reckoned with. And his knowledge of the family, combined with medical qualifications, made him a central figure in the Toorak drama. He was often called upon to provide his expert opinion in court and coronial settings. And he was highly regarded in the medical community, as well as being popular with his patients, thanks to his gentle nature.

It seemed almost natural then that he would take a lead role in the investigations surrounding Norma’s death, becoming something of an advocate for Norma and the family. To the police, as we’ll see later, he became a proverbial thorn in their side.

But, was Dr Williams determined to find the ‘truth’ or simply protect his family from prying eyes and exposure? Norma’s death would attract so much interest as inquisitive onlookers vied to learn more about her private life. Naturally, this meant speculation about her broader family relationships and the community in which she lived.

To understand this fascination and the importance of privacy in the Toorak community, we need to learn more about the context of time and place. What was Norma’s world like and what was her place within it?