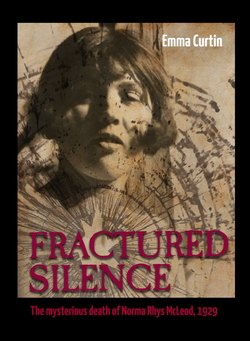

Читать книгу Fractured Silence - Emma Curtin - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Two Norma’s world: Toorak in the 1920s

ОглавлениеThe Melbourne suburb of Toorak is about five kilometres south-east of the city's central business district. It sits within the municipality of Stonnington, although in 1929 it was under the domain of the City of Prahran council. Today it has a population of approximately 14,000; in 1920 about 5,700 people called Toorak home.

Despite having a less than elegant name, meaning ‘weed in lagoon’ or ‘reedy grass’ in the Kulin language of the Yalukit-willam people, Toorak has always been, and still is, synonymous with wealth and privilege. As Sally Wilde stated in her history of the area, the suburb has “traditionally been the home of Victoria's most affluent citizens and … the hub of the kind of activities that were reported in the social pages of the newspapers”.

In the nineteenth century, Toorak was known for its grand gentlemen’s houses built on acreages of manicured lawns, tennis courts, conservatories and beautifully kept gardens. It had the largest number of private houses of more than 12 rooms than anywhere else in Victoria.

During Melbourne’s land boom of the 1880s, developers began to look at opportunities to subdivide large estates in Toorak. The depression that followed in the 1890s had an economic impact on many of those in the large private mansions of the suburb, creating new opportunities for subdivision. Selling first-class real estate helped many of the financially-hit recoup their losses.

By the beginning of the new century, grounds were being divided, new streets created and “building allotments in prime positions appeared throughout the district”. By the beginning of the First World War, land in Toorak was “selling for £18 to £20 per foot, whereas in Prahran [its neighbouring suburb] the going rate was between £6 and £8 per foot”.

According to Wilde, Toorak didn’t suffer a decline in status as old homes were demolished or their lands sold off. “On the contrary”, she said, “if anything, the status of Toorak and South Yarra rose in this period”.

The aspirational, professional upper middle-class, to which the McLeods belonged (Major Norman McLeod, Norma’s father, was a civil servant working for the Department of Defence; his father had been a storekeeper in Beaufort, a small country town about 170 kilometres west of Toorak), saw the area as a perfect place to build their own dream homes with all the latest conveniences. This sentiment was captured in a 1927 advertisement for the Mayfield Estate: “All Australia knows Toorak as Melbourne’s outstanding residential centre. It is a name synonymous with the best in home life, its excellence being the standard for comparison”.

On 19 August 1912, Norman McLeod bought his prestigious piece of land on what was known as the Mandeville Estate (part of the land originally belonging to Mandeville Hall, now Loreto Hall Girls’ School). The estate had first been advertised in 1902, promoted as “finely situated” in a “select neighbourhood”. Norman bought the land from builder Matthew Cumming of Prahran for the sum of £1,000, which represented about eight times the average annual salary at that time. Norman had taken out a mortgage with the National Bank of Australasia, which wouldn’t be discharged until after his death. So he was clearly not a man of ‘family money’, like many in the Toorak community, but he was a man of ambition who obviously valued social status.

Mr Cumming also built the McLeod home, as well as other properties in Mandeville Crescent. He’d complained to the Prahran Council in 1910 about “the trouble he was put to in connection with the sewerage in Mandeville Crescent … his two brick villas were left unsewered”. And in May 1912 he wrote to the Council Surveyor: “I would esteem it a favour if you could asphalt the footpath in Mandeville Crescent Toorak from the corner of Orrong Road to the right of way in front of the new brick villas I am just finishing”. Once the sewers were fixed and a footpath laid, the McLeods moved from Williams Road, Hawksburn into their new Mandeville Crescent home in 1913.

The McLeod house exterior reflected the style of the day and an elegance that is still admired today. A picket fence marked the boundary of the front garden, with a low hedge adding to the screening. Two small native trees adorned the entry to the house.

A grainy newspaper image of the McLeod home in 1929

On the right-hand side (as you faced the house) stood another residence, at about nine metres distance. Another house sat beyond that, built on the corner of Mandeville Crescent and Orrong Road. On the left-hand side of the McLeods’ home was the Toorak Bowls Club, founded in August 1913 and still operating to this day. The club and Norma’s house were separated by a narrow lane of bluestone slabs. According to the Melbourne newspaper the Herald, “although only 50 yards [about 45 metres] from Malvern Road, Mandeville Crescent is a quiet locality. Most of the houses are of a similar type – red brick and built on fairly standard lines”.

Mandeville Crescent’s houses reflected the trends of the day. By the early 1900s servants were in short supply and no longer seen as necessary trappings of the privileged life. Families were also smaller. This meant that the new affluent suburban homes could be more streamlined and functional. Tastes and conditions had changed.

So, with a new century came a new style of architecture. Out of vogue were Toorak’s Italianate buildings of stone and stucco. The tendency now was “towards a less formal style of living, [which] led to the Queen Anne style with its free flowing arrangement of rooms, in contrast to the symmetry of buildings of the previous century. Distinctive features included red brick, terracotta roofing tiles, gables, dormer windows and timber verandahs”. But these houses were still fairly grand. James Paxton, who grew up in Toorak in the 1920s, wrote about these new villas in his memoirs: “Their appearance was deceptive as they were surprisingly roomy inside … all rooms had high ceilings of fifteen to twenty feet and elaborate plaster mouldings executed by master-craftsmen. Every room had a fireplace for burning black coal and mantelpieces were usually fashioned of exquisitely carved marble”.

This was the design the McLeods adopted in their own Queen Anne style home. Derived from the English architectural revival of design elements from Queen Anne’s reign (1702-14), houses in this style were intended to create a sense of grandeur, even if on a small scale, with elaborate roof lines and high ceilings of detailed plasterwork, often using art nouveau motifs. Some Queen Anne houses used timber panelling on lower walls in front rooms. Otherwise rooms had picture rails and made use of a growing range of wallpaper options, or pressed metal.

The McLeods’ double-fronted red-brick villa had nine rooms. These were: a large formal drawing room at the front of the house over-looking the crescent; a dining room at the rear, next to a small kitchen; a study, also at the back of the house; a boxroom or dressing room across the passage from the study; and two large bedrooms. There was also a bathroom, although the toilet was outside - the idea of toilets inside the house was still not common, even in new houses built well into the 1920s. A laundry was accessible via the back of the house. Verandahs adorned the front and back, in keeping with the Queen Anne style. Fireplaces warmed the key rooms of the home.

I haven’t been able to find any descriptions or images of inside the McLeod home in 1929 … and it would be a couple of years into my search before I walked into the house, which I’ll get to later … but I did learn a little bit about their furniture from an auction notice printed after Norma’s death. This gives us some insight into family life. The auction advertisement highlighted “superior household furniture and effects”, which included an “Upright orchestral GRAND PIANO, by Cable”. The Cable Piano Company was an American business based in Chicago; Suttons of Bourke Street were their agents in Melbourne. They also had an outlet in Ballarat and it’s likely that Norma’s mother, Edith McLeod, had bought the piano with her from her family home in Ballarat, where she was born and raised.

I would later discover that Edith came from a very musical and literary family – her father Abel Rees had been raised in the Welsh Congregational Church. He was a lay preacher known for his poetry and musical associations, including the organising of annual Eisteddfods in Ballarat. Several articles in the Ballarat Star in the 1880s recorded community events where either Edith or one of her eight sisters sang, usually for church-related causes. Other members of the Rees family also showed great talents in music. It seems highly likely then that Edith would have passed her passion for music to her children – maybe Norma too enjoyed playing on the grand piano. Norman was also known to play, although visiting family members were not always appreciative of his “banging away” at the instrument.

Other furniture items listed in the McLeods’ auction included “Splendid Carpet, Lounge Suite, in Cor. Velvet [corduroy velvet]; Walnut Bedroom Suite, Wireless set, Electric sweeper, Lot of Good Crockery and Glassware”. Carpets in the 1920s were not fitted as we know them today, but were bought in squares to decorate and warm polished wooden flooring. In this decade, Australia was by far the largest export customer for British carpets. Bathrooms, and sometimes even bedrooms, had linoleum flooring. Keeping carpets clean made the electric sweeper or vacuum almost a necessity in the average home, although they were still something of a novelty in this period. The growth in the use of electricity was one of the outstanding developments of the 1920s, with “the large-scale conversion in Australia of lighting, of machinery and household appliances to electric power”.

Corduroy velvet lounge suites, like the McLeods’, were popular ‘must-haves’ for the well-to-do 1920s home. The Big Paterson furniture company in Fitzroy, for example, promoted fawn or blue velvet corduroy cushion lounges in 1924 as “a most comfortable lounge” of a “very pleasing design” and “wonderful value” at £35 (the minimum wage in 1924 Australia was about £220, so these suites would certainly not have been within everybody’s reach). The walnut bedroom suite listed for sale may well have been Norma’s, perhaps bought locally from C. P. Jeffery in Prahran, similar to one shown in a 1928 advertisement (below), and now sadly redundant.

The McLeods’ advertised ‘wireless set’ was a bit of a luxury item. In 1924, the Weekly Times recorded that “It is only twenty years since Marconi first demonstrated the possibility of sending and receiving sound waves through air. Now many thousands of people are listening on wireless receivers in their own homes”. But, it noted, many of these receivers were homemade at the cost of a few pounds. Until mass production brought costs down, shop bought sets were only affordable to the affluent.

Advertisement in the Advocate, 22 November 1928

Like their ‘automatic’ telephone, the wireless set and everything we know about their home suggests the McLeods liked to display all the trappings of their status as respectable members of the affluent Toorak community. Their home was an important symbol of their place in society.

Norma had lived in this “fair garden home”, as it was poetically described in the press, from the age of 14.

While I had a shadowy image of her, cobbled together from newspaper accounts, I wanted to know how Norma had spent her years in Toorak and what kind of a woman she was.