Читать книгу Still - Emma Hansen - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

LESS THAN AN hour after we get home my first contractions start. Hanah has just arrived with Carson, and her confusion over my still-full belly is palpable. Annette called her when Hanah was on a ferry to Vancouver Island. As she heard the news, she slid down the cabin wall and came apart on the floor, gasping for air. Somehow, she is here. She has never been one to hide emotion, and I can see how hard she is trying now. I feel the toll this is taking on her, and for a moment it distracts me from my own pain.

The rushes roll in gently at first—every three minutes, but manageable with a little focused breathing. My body is ready. My mom sits next to me on the couch, careful not to touch me, but her presence is grounding. Friends plays on in the background.

I pick up my phone and open up the contraction timer app I downloaded months ago in preparation. Every time I hit record my mom looks to me and asks, “Another one? So soon?”

By nine PM I can no longer divert my focus with TV and deep breaths. It’s starting. I ask everyone to leave, though the goodbyes are a blur.

Aaron is running a bath behind me, and I am bent over the counter riding out another contraction. We paged the hospital a few minutes ago, asking if I should be in so much pain so soon. Susie, the new midwife on call with our birth program, told us the Cervidil could sometimes cause intense and false contractions. “Take it out,” she suggested. “Just like you would a tampon. Then hop in the bath. The warm water should help you relax.” Before hanging up, she added, “Come back in the morning for another dose, but only once you’ve slept. Really do try to get some rest.”

I climb into the tub to soak as Aaron props himself up on the ledge. We try to talk through what is happening.

“Maybe we’ll be one of those inexplicable medical marvels and he will come out screaming,” Aaron says.

Yes, maybe that’s it. I’ve read the articles that sometimes circulate on Facebook about babies they thought were dead who were placed on their mothers’ chests, then suddenly cried out. I am skeptical, but I don’t want to be. We believe in God—a God that is good. We believe that miracles are possible through Him. What is that belief for, if it can’t help us now?

So we start to pray. We pray that He will save our child, bring him back to life, change what has happened. We believe that He can. And just in case, wanting to cover all of our bases, we pray that the doctors are wrong and that he isn’t dead. Surely, he will be born and he’ll take his first breath and everything will make sense again. I want to hold out hope that our miracle is within reach, that the fact that our baby has died on the same day Jesus was crucified is significant. There’s something to that, isn’t there?

Only that bellowing voice of the fiercely protective mother is gone; she speaks solely in moans now. Making it through this experience with our baby alive doesn’t really seem like an option. But how desperately I want to believe that it is.

The bath isn’t helping. I turn the water back on, all the way to hot, hoping it will burn away the pain. Having spent the better part of a year soaking in lukewarm baths to keep our baby safe, I am shocked by the heat.

“When I was pregnant—” I start, wanting to explain to Aaron what I am feeling. But I stop, not sure how to continue. Am I still pregnant? I remember the saying, “You can’t be just a little bit pregnant.” We think of pregnancy as a very clear “you are or you aren’t” situation, so much so that it’s inspired the idiom meaning there’s no gray area or uncertainty. But what about when you are still carrying a child, but not a living one? I shudder at the thought and don’t continue my sentence. Aaron doesn’t press me for more.

Soon, I can’t make it through my contractions without clutching Aaron’s hand, fighting back against the force of them. We had decided that we would try to labor at our place for as long as possible—that was one of our only hopes from the start of this pregnancy and we wanted to stick to our basic birth plan as much as possible. But we need help. Aaron calls our doula, Jill—he has been texting her with updates since we were in the hospital—and asks her to come over. My contractions are now just over a minute and a half apart, lasting for sixty seconds. That leaves me thirty seconds of rest in between them, and it isn’t enough. Nothing could ever be enough for this. “I can’t do this without pain relief anymore,” I moan. “We need to go in.”

Aaron looks relieved to have something to do. He calls Jill again and tells her to meet us at the hospital instead, then gathers our things by the door. By 10:50 PM we are off.

Ten minutes later, we are back at Admitting. A nurse greets us, smiling. “Are you having contractions?” she asks cheerfully.

“I am,” I start, pausing to breathe through one. She waits, and I squeeze my eyes shut as I sway. “But we’re here under different circumstances,” I continue. “If you look up my name, you’ll see.”

She looks at me from behind the desk, clearly confused, and asks again if I am in labor. “You’ll just need to sit in the waiting room and we’ll call when we have time to admit you.”

I can’t believe her. How does she not know what happened? How has the whole world not stopped to grieve with us? I shout at her that my baby died, that I was induced, that I need to be seen right away. I am spitting venom at her, and only my depleted energy holds me back from causing an even bigger scene. I am not even embarrassed. I am angry, and that anger feels good.

Another nurse, one I recognize, quickly appears and ushers the baffled nurse to the side. We are taken to a desk where the administrator takes our information. Another contraction starts. I grip the armrests and close my eyes in response. Jill comes in and immediately runs toward us. She places her hands on top of my shoulders, pressing down firmly and whispering, “You’re on top of this.”

A nurse takes us into an admitting room, not the same one we were in earlier, and shuts the door behind her. We wait through more agonizing rushes. I ask for pain relief, whatever they can give me. I’d planned on having an unmedicated birth, but at home I changed my mind and decided I wanted it all. “Anything you want,” Aaron said.

They wheel in some sorry-looking nitrous oxide with a broken hose. I try it for a few contractions and give up. It doesn’t do anything for the pain and it only restricts my breathing, which is strained and quick. Jill puts the TENS machine on me—its electrical pulses are meant to help me cope with the contractions—but it doesn’t have time to work. I’m already in full-blown labor.

Then she tells me, “I am going to take some pictures for you and Aaron.” I look at her quizzically, wondering why we would want pictures of any of this. “You don’t ever have to look at them,” she continues. “But just in case you want them one day, I’ll keep them in a safe place for you.”

“Alright,” I say. I don’t understand, but I trust her.

I request an epidural, as soon as possible. The exhaustion, the emotional toll, the physical pain, the mental agony—they are all at levels beyond what I can handle. If I’m going to finish this, I need just a few minutes to regain an ounce of strength.

Our midwife, Susie, arrives around midnight. She exhales audibly as she steps into the room. Her hair is braided down her back, with small wisps escaping at the nape of her neck. She gathers gloves and gauze and tools from a tray, the crystal bracelets stacked up on her wrists rattling as she works.

“Susie has lost a son too,” Jill says.

“Really?” I gaze at her desperately, and she nods. I can almost sense her ache. I wonder if this kind of pain will be obvious to me now, a secret language spoken among a secret club of the bereaved. Learning that she knows the pain I am feeling, I feel instantly heartbroken and grateful at the same time. There she is, still living, still moving, still delivering babies even. Somehow, she is surviving. Maybe I will too.

Susie asks if she can perform a cervical check. She talks me through each step, gently preparing me for the discomfort. “You’re seven centimeters,” she announces. “I don’t imagine it’ll be long now.” She smiles kindly and hurries out the door to speed up our admitting.

Later, I will learn that the nurses originally booked us into one of the smaller rooms in the windowless birthing suites on the first floor, the ones with paper-thin walls that let in the cries of mothers and babes from the other rooms on all sides. Jill and Susie advocated to move us upstairs, where the rooms are new and spacious and beautifully renovated, with windows looking out to courtyards. Upstairs, we don’t have to see or hear what we’d longed to experience ourselves. Not much can make our situation better, but that small act certainly does. At least our birth will be our own.

At one thirty the anesthesiologist comes in to administer my epidural. He is young, another resident, but he is calm and confident. I start to relax, a little. I’m already fully dilated and can feel the pressure of the baby’s head, but if I have just a few minutes to breathe, everything will be alright. The anesthesiologist numbs a patch on my spine, inserts the epidural catheter, and starts the drip. The cool rush of fluid passes through the tubes over my shoulder and I breathe through the next few contractions. As they start to slow down, I catch my breath. I bring myself back into the room and notice it is unexpectedly calm. Our midwife, our doula, and the labor nurse surround us, steadily going about their jobs. No fussing, no panic, no rush. There is peace—one I imagine could be attributed to God. It’s strange to say, but suddenly the birth feels like the one I’ve been imagining. It feels beautiful.

My waters break in a dramatic gush shortly after the epidural. With one quick check Susie quietly says that it’s time to start pushing, if I’m ready. I look to Aaron and have to blink away the tears. This is it. We are about to bring our son into the world and then, too quickly, say goodbye. I look at the clock—it’s 2:00 AM on our due date—and grip Aaron’s hand as I nod. I start to breathe our baby down and out, fully aware of every movement despite the epidural, as I gently push through each contraction.

“Remember to smile,” Aaron whispers in my ear.

I forget myself for a moment and laugh as I bear down. He squeezes my hand and smiles with me. We’d been told in prenatal classes that smiling during the pushing stage could help minimize tearing. There’s no longer a need to worry for the health of our baby, so he directs his worries to me. That he remembers this and voices it is a tremendous act of love.

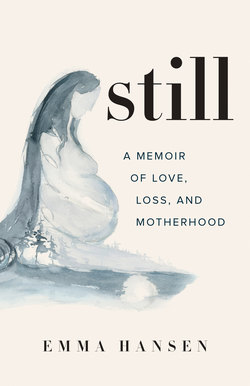

Jill keeps assuring me that I’m doing an incredible job. She tells me my body is made for this, encourages me by saying that everything is stretching well. Then finally, a few pushes later, relief. I take our baby from Susie’s hands and pull him up onto my chest. Aaron cuts the umbilical cord. At 2:24 AM on April 4, 2015, our beautiful son is born, still.

IN THE IMMEDIATE moments after his birth, we pore over every flawless inch of his strong body. He is the perfect mixture of us both. I see Aaron’s nose, head shape, and long fingers and toes—he would have been tall. But he has my eyes, dimpled chin, and shock of black hair. I don’t believe it’s bias when I think that he’s a striking baby. These moments are both the happiest and the most painful I’ve ever known. There will never be enough of them.

Then Susie says the words we never thought we’d hear:

“We know what happened.”

“You do?” Aaron asks.

“There’s a tight true knot in his umbilical cord,” she replies. This knot is what killed him. Jill shows me a photo on her camera, zooming in on the center. The cord is dark and rich with life-sustaining fluids on one side of the knot, and on the other side, the one closest to his body, it is pale. Nothing was getting through. He was starved of all that was created to provide for him.

I don’t ask to see the real thing. It doesn’t occur to me that I might need to hold the knot that took the life from my own flesh and blood. Later, I will think I would have appreciated knowing how that felt.

True knots are rare, happening in about 1.2 percent of all pregnancies. And even more rarely are they fatal, because usually the knot doesn’t tighten so severely.1 We are told he must have done a few somersaults and tied it when he was very small—it was so close to his body. Then when he dropped in preparation for his birth, it would have tightened—slowly or quickly, we’ll never know.

My heart is heavy knowing what happened. On one hand, it’s a small relief to know it wasn’t something we did or didn’t do: ultrasounds can find knots, but because they are so rare, they aren’t routinely screened for, so often go undetected. But that same knowledge brings tremendous grief; his passing happened completely out of our control. We couldn’t have protected him from this.

Our labor nurse, Rose, looks at him lying on my chest. “He’s perfect,” she says. “Does he have a name?”

“Reid.”

We decided months ago. We started referring to him by name in the third trimester, even though we kept Theo as a backup. But Reid fits him—a tribute to my maternal grandfather, Patrick Reid. Parents, siblings, and friends all used it, near the end. We knew who he was meant to be.

Aaron calls both of our parents: “He’s here.” Less than an hour after his birth, my parents arrive. I watch with pride as they lay eyes on him for the first time, gushing over how perfect he is and commenting on which of us he looks like and why. Then I fall apart as they too mourn the loss of a life they have held close to their hearts. It dawns on me that though he died before anyone got to know him, he still made an impact, is still loved, and that many are grieving his death. We are not alone in this loss.

Time passes; nurses come and go. My wet sheets are changed out for fresh ones; I’m given a new hospital gown. Aaron sleeps now on the couch next to my bed, and my parents doze in the corner by the window. It’s still dark out, and the room is quiet. I lie with Reid in my arms. When I close my eyes, I can so easily pretend that he is just sleeping too, that any second he’ll wiggle the way he did in my belly, or cry out to be fed. I memorize the weight of his body in my arms, imprint the image of his face in my mind.

I’m not an early-morning person. I’m not even a daylight person. That’s not to say I’m not ambitious, but days often slip away from me. I can probably count the number of sunrises I’ve seen on both hands. They’re sleepy and cold and pass too quickly. I’m a sunset child. A creature of the night, who thrives on the light from the moon and the stars. My best work is done past midnight. For me, three AM is bedtime, not rise-and-shine time.

The moments before the sun appears can take your breath away. Adventures of the night. The wine-filled evenings with secrets that linger in the air. Those times you went skinny-dipping. That night those sparklers singed your hair. The dreams you lived in before they escaped into the morning sky. The birth of your first child.

In these hours while the dark endures, I hold on to the time that the black skies give me, illuminated only by the stars and the lingering effect of the full blood moon of the eclipse. Until sunrise, Reid is heavy in my arms and perfect in his body. With family surrounding us, and without the reality of the light, I can almost imagine everything is as we’ve dreamed it would be. And in many unexpected ways, it is.

When the sun comes up, the clock will start ticking. We are on borrowed time; Reid has already started to change. But for this moment, in the magic of the night, he is safe in my arms, protected from the harshness of light and time. Reid is simply my baby who has just been born.