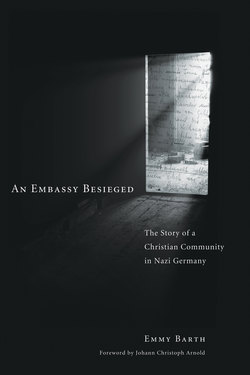

Читать книгу An Embassy Besieged - Emmy Barth - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Hitler’s Rise to Power

ОглавлениеWhile the disillusionment following World War I had driven Eberhard and Emmy to find a positive alternative in a life of love and social justice, Adolf Hitler found scapegoats for Germany’s troubles in Jews and communists. By 1920 he was a star speaker of the National Socialist Worker’s Party, expressing the deepest fears and desires of his listeners and exuding confidence in his uncompromising, aggressive speeches. But his attempt to take over the government in November 1923 in the famed Beer-Hall Putsch came to an ignominious end, leaving him under arrest with a dislocated shoulder.

However, Hitler was released on parole a year later and immediately began building up his party again. Fiery speeches, marches, and staged street fights gained the attention of the press and won new adherents. Hitler encouraged ambitious, ruthless young men to take leadership positions. As Max Amman, the publisher of Mein Kampf, said: “Herr Hitler takes the view today more than ever that the most effective fighter in the National Socialist movement is the man who pushes his way through on the basis of his achievements as a leader.” Ernst Röhm had built up the Nazi Party’s paramilitary group, the Sturmabteilung (SA or storm troopers), before the 1923 putsch. Although it was declared illegal after the putsch, it continued to grow to thousands of members in the late 1920s and into the 1930s: street violence escalated.

Eberhard Arnold wrote of his impressions of the mood of the country in a letter:

Once again heavy clouds hang over Germany. The general crisis in world capitalism has oppressive consequences for us. I don’t mean the occupation of the Ruhr territory and the economic demands of France, etc., although this enslavement of a great working people is among the most terrible things in the history of humankind. But still more terrible is the repugnant contrast between the new wealth which, without the least refinement, takes possession of everything, and the new poverty which is increasing, with poorer nutrition and freezing conditions. I have heard of families who have introduced two days of fasting each week, simply lying in bed so they can spare the heating fuel. But it will get worse when, as a result of the scarcity of coal and the decrease of foreign trade, unemployment increases. Already now many factories work only three days a week or only half day, with half activity and half pay. Nevertheless the young workers with full working strength have on the whole enough to eat and to live on. It is more difficult for the older family fathers, and worst of all for families without a strong, healthy breadwinner. As a result the children and the old people suffer the most.

In the heavy spiritual fight behind all these outward horrors that weigh us down, one can sense everywhere a deep disillusionment and a general depression, especially in socialist, communist, and pacifist circles and in the radical youth movement. There is a sharp increase of grim nationalism. The new bitterness over the world situation is expressed not only in helpless anger against fate, in a general apathy, or in anxiety over one’s own personal life. Rather it is expressed primarily in ever wider circles of young people in hatred against the French and the Jews, in tough preparations of new militaristic formations, which of course would be unthinkable without a military conflict in the Entente itself. And yet it seems that these so-called nationalistic and swastika circles have no real content. It is again merely love to those nearest, and hatred against those further away, the common struggle for economic existence, a somewhat wider circle of empty egoism. Where are those people who, when the critical moment comes, will refuse to join in killing or harassing, who will rather be crucified and bear the sign of the crucified one? There is a great emptiness, a great vacuum. What will fill this void? Will it be the old filth again, the old consolation of degenerate nature, or a new fresh wind of purest air, the holy breath of God? Now is the moment to proclaim the truth everywhere, now more than ever! In speech, song, and speaking chorus, through pamphlets and books, above all in work and life, and through community of daily action, the one and only message must be spread abroad: Jesus. We believe in him, that his future will again become the present, that his power must be proved anew in following his life. This is the miracle that is always new.1

A cult developed around the person of Adolf Hitler; the “Heil Hitler” salute became compulsory in the movement in 1926. A rally in August 1929 was attended by forty thousand admirers. Nazi organizations were set up to cater to the needs of particular segments of society such as factory workers and artisans. Young people were targeted by the Hitler Youth (which began as a recruiting arm of the brownshirts), the League of German Maidens, and the National Socialist German Students’ League under the leadership of Baldur von Schirach. The Students’ League campaigned for limiting the number of Jewish students and dismissing pacifist professors.

President Hindenburg’s seven-year term ended in 1932. He was eighty-four years old and ready to retire, but his supporters encouraged him to run again out of fear that otherwise Adolf Hitler would be elected. Reluctantly, he agreed. Hitler campaigned vigorously. He rented an airplane and flew from town to town across Germany, delivering forty-six speeches. Although Germany’s major parties backed Hindenburg and he won easily, the Nazi propaganda paid off. Hitler won 37 percent of the votes and National Socialism was clearly a force to be reckoned with.

New Year’s Eve 1933

Members of the Rhön Bruderhof anxiously observed the shifting mood of their country. Eberhard Arnold’s youngest son Hans-Hermann wrote to his brother Hardy in June 1932:

At the moment we live in a very difficult time that could spell disaster for us. I am thinking of the political situation and National Socialism . . . I have a feeling that the time of our expulsion and emigration is near.2

In January 1932, Emmy Arnold’s sister Else von Hollander died of tuberculosis. Her death was a great loss to the community. She had been part of the family since the first years of Eberhard and Emmy’s marriage and had worked faithfully as Eberhard’s secretary for years: recording meetings in shorthand, typing letters, and assisting in his research and publishing work. At the same time, her Christ-centered experience of death and dying was a challenge and inspiration for the still-youthful Bruderhof.

The community had grown slowly and steadily over the years. Another of Emmy’s sisters, Monika, had joined them. She was a nurse and had married Georg Barth; they had three young sons. Adolf Braun, a veteran of the last war with his wife Martha and their two daughters had been with them since 1924. Others had also experienced the first years in Sannerz like Karl Keiderling, a former anarchist, with his Irmgard, as well as the teacher Trudi. And there were newer faces: Hannes and Else Boller from Switzerland, Nils and Dora Wingard from Sweden, and some young single men and women.

Eberhard and Emmy’s oldest daughter Emy-Margret had married Hans Zumpe; their first child was the hundredth member of the community. Hans had come from a family of civil servants and had shown considerable organizational skills. He helped with the accounting and bookselling and gradually assumed greater responsibility for the spiritual leadership of the community. The younger Arnold children were still in school: Hardy was studying in Tübingen, hoping to help his father in the publishing house. Heiner was taking a practical training in agriculture, and Hans-Hermann and Monika were still in high school.

Every New Year’s Eve, the community met at midnight to remember the year that was ending and express hopes and wishes for the coming year. At the New Year’s Eve meeting in 1932, Eberhard spoke at length about the worrying political and economic developments of the world around them.

We stand at the end of the old year and before the new, as at a winter solstice. Will it become still darker? Still colder? Or will the New Year bring again more light of love, more warmth of righteousness, more joy of community among people? Will a new humanity come about again, or will men grow still more inhuman?

The hour of the world in which we stand at this historic moment shows itself, even to the most superficial observer, as an hour of the greatest crisis and decision. But it is necessary to see things quite apart from the daily newspapers, which, in a mass of detail, give such an unclear survey of events that most readers do not notice what is really happening. We must attain a view of the present world situation which grasps the essential events without being clouded by unessential diversions.

It is not by accident that we live here in Germany right between the eastern and western powers. On the one side is the liberalism of the French Revolution. On the other side the attempt has been made in Bolshevism to limit free trade and free enterprise to the absolute minimum.

Eberhard went on to explain how the prevailing domestic and global tensions must lead inexorably to the rise of dictatorship in Germany and ultimately to a catastrophic world war:

This new nobility of the oppressed proletariat exercises an unrestrained dictatorship. Again and again they have to resort to deeds of violence and to bloodshed.

And to the south? In Italy a renegade socialist has become a dictator wielding the weapons of militarism and mass-suggestion. Mussolini takes Caesar, the first of the Roman emperors, as the model of the modern statesman. He wishes to attain world rulership, making the state, the Roman Empire, into a god, just as it was at the time of the Roman Caesars.

In Japan and China and on other parts of the earth, there is further unrest and war; thus we are living in a continual state of war, which brings with it uninterrupted, never-ending bloodshed. At the same time, between the opposing ideologies mentioned above, in spite of all peace treaties, the new and perhaps last world war is being prepared. It will necessarily be considerably more barbaric than the last world war, because poisonous gases and other techniques of war have become absolutely demonic in nature. A ruthless war will be led, not only against men and military bases, but just as much against women and children far from the front.

The parliamentary form of government in Germany is finished. It has governed itself to death in these last ten years, and it can be assumed that we will soon be under a dictatorship. This state leadership stands between parliamentary democracy on the one hand and revolution on the other. The parliamentary, liberal power cannot prevail, and the revolutionary power has no prospect in the present distribution of power to win control through violence. Since both of them cannot rise up, the consequence is evident: the Reich president and the Reichskanzler will take over complete power.

Man’s confusion has reached its peak. The present hour is such that a political catastrophe must be approaching, because the present suspense is not tenable. In the spiritual outlook of the world there reigns an absolutely hopeless confusion. No one knows any more whom he can trust or upon what he can rely. That is the position at the present hour of the world.

In the midst of this mounting crisis, Eberhard believed that Christians had a responsibility to continue God’s work.

We stand now confronting this—a most insignificant group of people, so small and so lacking in talent that we cannot even be thrown into the scales against present events. What can we do against these political and spiritual powers? We are less than a gnat on an elephant, less than a grain of sand on the seashore, less than a drop in a bucket of water. And yet our faith tells us that this does not matter. For it is not that you have something to say, that you have responsibilities, that you have something to bring into the world. Rather, that which is planted within you must be brought to the whole world. You need not worry to what extent you personally will be used. You must have the faith that what is said and given to you must be said and given to the whole world. Therefore you must be ready for the new hour, for the new day that will come over the world. You must be ready to do your utmost in our small, insignificant work. You must be very courageous; the hour demands it of you. In the face of these great events you must not be found too small. In the face of God’s great plan you must not be found too petty.

How can this come about? We do not know. We have no money to build houses, to buy farms, to clothe people, to strengthen our economic basis so as to feed an additional forty people or more. And yet we are filled with the belief that there is only one possible answer: the unity of the church, the righteousness of God’s kingdom, the spirit of God in Jesus Christ and his coming reign. Therefore we must be prepared now to risk everything. We must build. We must enlarge the farm. We must increase the publishing work, the printing and bookbinding work. Love demands that we throw ourselves in with all our strength for this need of the world.

Then we must go out. Through the publicly spoken word and through the publishing house and print shop, through letters to our friends, through messages to the governments of all states we must send out the good news. We must call everyone to the way of communal brotherliness and allow them to be released from strife and once more be united with the spirit of the future, which is the spirit of righteousness. This is only very little of all that should happen in the year 1933 if we have faith.

Therefore we come together to call upon God. In him we find an answer for what is to happen, for that which moves the whole world, and what has to be done in the face of this hour.

If this is our certainty, then—to work! All hands on deck! Let us dare it, whatever it costs!3

Eberhard walked up to an unlit Christmas tree in the center of the circle and lit one of the candles. One by one, others expressed their hopes for the New Year and lit their candles. They spoke with courage and determination—even a solemn joy—of the witness they wished to give.

Midnight struck: 1933 began—a year that would bring greater changes and challenges than Eberhard could have imagined.

But the mood in the meeting room was hopeful and courageous. After the older people and parents of little children went to bed, the young people went outside. The light from the full moon reflecting on the snow was bright enough to read a newspaper by. Much too beautiful to go to bed! Someone started a folksong, and they joined hands and danced for a long time.4

v

“President Hindenburg has appointed Adolf Hitler as Reichskanzler.” At the dinner table in Fulda all conversation ceased as everyone listened to the rest of the radio announcement. Knowing that the community had no radio, Heiner went to the telephone and called his father. At the other end of the line Eberhard was silent for a moment. He was not completely surprised; for the past three days the papers had been filled with speculation as to who would replace Schleicher, who had been forced to resign. “The president has no idea what demons he is conjuring up,” Eberhard said to his son.

Most Germans trusted that their parliamentary system and the conservative members of the cabinet would contain Hitler’s ambitions. Under the Weimar constitution, signed into law August 11, 1919, power was divided between the president, the cabinet, and the Reichstag (or parliament). The president was elected for a seven-year term; Paul von Hindenburg, elected in 1925 and reelected in 1932, served in this capacity until his death in 1934. The Reichskanzler was appointed by the president and accountable to parliament. Few could have imagined how quickly Hitler would seize complete power. That evening at the Rhön Bruderhof, Eberhard shared the news with the community. He encouraged everyone to trust that God still held his hand over the country. Later that night Emmy wrote to her three sons who were away at school: Hardy in Tübingen, Heiner in Fulda, and Hans-Hermann in Buchanau.

The moment of crisis is here, and Hitler is Reichskanzler. We have to wait and see what will happen. Papa does not see it as too critical at the moment, since Hitler will be in the government together with Hugenberg and von Papen and others.* We ask you for now to behave quietly and cautiously. We will take communal action as soon as any laws are passed that we cannot reconcile with our conscience; that is, we will send a petition to the government. But it is also possible that for the present things will go on as before. By the time you come home the situation will have become more clear to us. In any case, we want to put ourselves completely under God’s protection, and faithfully follow the way we began. The times are such that each has to do the best as he sees it. In our brotherhood everyone is calm and prepared to face what lies ahead. If anything extraordinary is imminent, you will come home before we do anything. May God protect you and us.5

That night all over Germany the Nazi Party took to the streets to celebrate their victory. Curious and naive, Heiner left the house and followed the crowds. Fulda was a small, conservative Catholic town. But young Nazis had come in from neighboring villages, and he saw them on every street.

The Nazis in uniform marched through Fulda proclaiming, “Without bloodshed, we will not leave the village.” . . . I was very young; I did not know how serious it was. I thought, that is Berlin; it will take a long time before that comes to the Rhön. But Hitler acted pretty fast. It was all organized. Everywhere there was someone already appointed—immediately, completely disciplined and organized for an attack. It simply was amazing. I walked through the streets and parks, and everywhere there were these uniformed Nazis, who were not allowed on the streets a few hours before.

Near the center of the town there stood a uniformed Nazi with a terrific gift of speech. He spoke to the masses, and more and more people came. He said, “We are now in power. Tonight Hitler will still be merciful; if you join the party tonight, he will still be merciful.” In Berlin the SA and the SS marched past the house where Hitler was, and he stood there with his arm raised for several hours while thousands of troops marched by. I do not know how he managed it.

I was not afraid. A meeting was announced in the city hall, the biggest hall of the town. There was a podium with a microphone, and in front of it there were two or three rows of SS in black uniforms with a skull and crossbones. I went into that meeting without permission from my father. I did not know how dangerous it was. There were many in that room who were not Nazis yet, but they were nationalistic. There was a speaker who spoke like the man outside, that Hitler is still compassionate. Then they sang “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles,” that is, “Germany, Germany forever.” That was not a Nazi song; it was sung under the Kaiser. Everyone had to stand up to sing that song, but I remained sitting. It was a big hall and very emotional. I thought they would beat me up, or worse, but I got away with it. When I told my father, he said, “What business did you have to go to that Nazi meeting?” That was the last time I went. 6

v

Adolf Hitler was Reichskanzler and Germany had changed. To Eberhard, this presented a new missionary challenge. Earlier, he had appealed to that which was of God in the pacifist, socialist, communist, vegetarian, and back-to-nature movements. Now he sought to find something of God even in National Socialism:

We feel as if we had been set down in another country; we live now in a different nation than we did a year ago. And we have a missionary task here in this new country. We can take on this task only if we recognize all that is positive in National Socialism. We must learn to understand the people, try to grasp the positive elements of what is moving among them. We must not face this phenomenal change cold-heartedly. In National Socialism there are the elements of family life, of the community of the nation, of the Old Covenant—shielding what is good and right from evil.

If one encounters such a national movement by simply rejecting it, finding nothing ideal, nothing good and positive in it, one soon finds oneself completely outside it. This we must not do. In the same way as we recognized the good elements in the German youth movement, in the movements that expected and longed for a future of justice and fellowship, we must find the vision to recognize the positive values in the present-day national movement.7

The conflict between the National Socialist and Communist Parties was well known, and it would intensify over the next months. Eberhard had been openly sympathetic to the communists for years, because of their support for the oppressed poor. On February 10, an article about the Bruderhof appeared in the Frankfurter Zeitung, a large, liberal news-paper. Already in its headline it referred to the community as “Christian communists.”

The Bruderhof lies at the edge of a wood on the windy heights. No road leads to it, no cars or trains pass it. Completely isolated from the rest of the world, it consists of several houses. The work is hard. The swampy meadow is evidently to become a potato field . . .

A girl of about fourteen with big blue eyes and blond hair that sticks out from her kerchief greets me with a simple, “Good morning.” “Are guests welcome here?” I ask. Yes, but I should wait a moment as the men are at devotions. She leads me to a room with blue walls and simple heavy furniture. This is the communal meeting room. On the table is a blue cloth, on the wall a simple black cross. After a few minutes the men enter. All have beards. We greet each other.

“Welcome! Come have lunch with us. You can tell us about Frankfurt and then we can chat.” The man who is speaking shakes my hand and slaps me on the shoulder as if we had known each other for years. Everyone laughs—including me. In their unrestrained, honest manner these people know how to win the friendship of strangers within two minutes. There are no conventions here.

Meals are eaten together. The community numbers 108 members including 54 children and youth. Eighteen families live on the Bruderhof, but only half of the children belong to these families. The others were taken in by the community. During lunch I am told: “The Bruderhof is a social, educational community of work, made up of men and women who live in voluntary poverty. They dedicate all their physical, spiritual, and emotional energy for a life of active love.”

At the Bruderhof there are no wages and no employers and employees as understood by capitalistic economy. Within the Bruderhof there is no exchange of money. The members lead a sharp inner battle against private property and against everything that can disturb the unity of their common life.

We spoke little about religion. To summarize in one sentence: The Bruderhof believes that the solution to all the religious and social questions of our time can be found in original Christianity. It is independent of any church but is considered by all denominations to be an example of early Christian community. All the people I met at the Bruderhof are good Christians, but also ideologically good “communists.”8

The name of the Bruderhof was here associated with communism in black and white before all Germany. The danger was obvious.

Tübingen

Eberhard’s oldest son Hardy was studying in Tübingen in southern Germany. One of his professors was Karl Heim, Eberhard’s friend from their years together in the Student Christian Movement. Because of this friendship, he invited Hardy to lunch once a week and every month gave him some pocket money. Heim was a popular professor of Christian ethics, and his lectures in the university’s largest hall were packed. Hardy recalled:

Every student could present questions that he would answer. But so that there would be no chaos, the questions had to be presented in writing. He would read out the question and call the student up to the microphone to discuss the question with him.

Professor Heim was talking about the Sermon on the Mount in this Christian ethics course. He represented that there were many different ways to interpret the Sermon on the Mount and that it was not valid for everyone. I was most surprised that what he said was absolutely different from what my father said. So I took a piece of paper and wrote down that I could not agree that the Sermon on the Mount was not for everyone. I believed that Jesus had taught the way of Christianity in the Sermon on the Mount, and that it was valid for us now. So he read this paper out and called me to the microphone, and we went into a discussion. He admitted that you could interpret the Sermon on the Mount the way my father did if you wanted to, but he said, “I have different interpretations.”

This episode, which happened at the beginning of my first semester, made me known among the students. They came to me and wanted to discuss the Sermon on the Mount with me.9

Another professor at Tübingen was Jakob Wilhelm Hauer who taught comparative religion. He had spent time in India and studied Sanskrit. He too knew Eberhard Arnold and was friendly to Hardy; in 1921, he had spoken at a Pentecost conference in Sannerz about “spirit and culture.” In 1933 and 1934, Hauer developed a new “German Faith Movement,” based on ancient eastern and Nordic religions, which became quite popular among young Nazis.10

Edith Boeker was one of Hauer’s students, and she was deeply impressed: “I had never experienced anything like it. Everything was represented: anthroposophy, National Socialism, theology, and science.”11 She wrote in her diary:

Last night Professor Hauer invited us to his house. He is the man of Indo-Germanic faith. One room has a whole corner consisting of windows without curtains, so one can see the trees. Many books, and a beautiful woman’s bust with big eyes and long hair. On the walls are Indian and Persian symbols. He is actually a professor of Sanskrit and is similar to Nietzsche with a large forehead and a hanging red-blonde mustache. He is very likeable, peaceful, going into everything calmly and clearly. I love the educated, artistic atmosphere.12

Hardy shared several classes with Edith, and they talked about the world views presented by Heim and Hauer. As he wrote:

There was a small group of students who met for lively discussions of essential questions of life, inspired by the points of view represented by the professors Karl Heim and Jakob Wilhelm Hauer. One represented a rational, pietistic, protestant theology and the other a mystic, mythological Indo-Germanic heathendom. Several of us were deeply impressed, because what Hauer had to say seemed more truthful and honest than Heim’s theology. To me it seemed that what was important was to be genuine: honest paganism—that is, love to creation that is nourished by the primal, though unredeemed power of nature—was closer to God and to Christ than hypocritical Christianity that is marked by compromise and self-righteousness.

On midsummer eve, 1932, we celebrated the summer solstice. Professor Hauer gave the fire speech. It was one of those occasions when the night seemed to breath and we humans felt closer to the source of nature than usual. After the celebration, some went to sleep next to the fire, and others talked until dawn . . .

After Hauer’s classes, some of us would get together over cake and coffee and talk excitedly about the questions that concerned us. Why has Christianity failed? In what has it failed? We all recognized that Hauer’s attack on Christianity was justified, but we also saw that he only criticized the hypocrisy of the churches without understanding the joyful news [of the gospel.] Into these questions, the testimony of original Christianity fell like a bomb. Here was something alive and all-embracing that transcended the confused teachings of Hauer in its power and universality.13

Edith Boeker and her friend Susi visited the Rhön Bruderhof in summer 1932, and early in 1933 they both decided to quit their studies and join the community. Edith wrote:

It became clear to me that there are two powers, darkness and light, and that each person has to make a decision between them. At the Bruderhof light rules! Killing evil men will not decrease evil . . . I knew I had to stay. I went for one more semester to Tübingen. Hardy, Susi, and I met every day and spoke about the absoluteness of truth. It is impossible that there should be more than one truth, as Hauer says. It is impossible that there are two ways, as Heim says—one for the churches and another for the Bruderhof, for example, on the one hand to recognize that people can live together in love and on the other hand to say that it is impossible for the masses.14

v

At the end of February, Eberhard took the train to Tübingen. Hardy had arranged for him to speak at the university. They met in the YMCA building where two to three hundred students and several professors were gathered. Eberhard did not wish to advertise the Bruderhof as such, but spoke of the need for a Christian witness. The lecture lasted an hour and a half and was followed by a discussion. Here Eberhard got a sense of what young people were thinking. One student, dressed in an SA paramilitary uniform, picked up on what Eberhard had said about nonviolence. “Have you ever spanked a child?” he asked. A young woman who was studying theology quoted Matt 10:34: “Jesus said, ‘I have not come to bring peace but the sword.’” Another student asserted that the apostle Paul had claimed the right of Roman citizenship and thereby acknowledged the emperor’s use of military force.

Clearly, the mood was already nationalistic and militaristic. Eber-hard countered all the arguments. “The followers of Christ have a special task, namely to live according to love, according to the heart of God.” Then he put forth an idea that would become a favorite theme of his:

I must confess that I have a double set of ethics. For the followers of Jesus there is a different set of laws than for the world. Pharaoh was an instrument of God—not an instrument of his love, but of his wrath. Christians are not called upon to represent the wrath of God, but his love.

One young man said, “Your community is a pest to the German people. You are refusing to help the Fatherland that is bleeding to death.”

Eberhard responded adamantly to these criticisms: “I want to point out to you that in a tense political situation you are accusing our Bruderhof of being detestable and dangerous. With this you are bringing an accusation against brothers who are earnestly concerned to live according to Christ. I ask you, as Jesus asked Judas, go at once to the authorities and inform on us. Though I myself am no longer of military age, yet I can be arrested for influencing others against military service. I am ready, but be clear that by doing this you are slandering my beloved Jesus Christ.” Surprised at Eberhard’s reaction, the young man and several others left the room.

For three evenings following Eberhard’s lecture, thirty to forty people met with him for a two-hour discussion. They were able to speak on a deeper level about unity and the Lord’s Supper, and also about the role of government.

Certainly the government is from God and should be recognized with respect, in so far as it fights evil and protects the good. But the government is not only from God; it is also from men. It is conducted in a purely human manner and from this point of view must be treated with extreme caution. Thirdly, government is also from the devil, for it is the beast of prey out of the abyss that we read of in the Revelation of John. Unless we see these three facts together, as they are clearly shown in the New Testament, then we cannot do justice to the government.15

v

Meanwhile, significant political events followed in quick succession. On the night of February 27, 1933, fire destroyed the Reichstag, the German parliament building. Hitler denounced this as a communist plot and used the opportunity to persuade President von Hindenburg to sign a decree “for the protection of the people and the state.” This Enabling Act suspended freedom of the press, the right of assembly and association, security from house-search and interference with postal and telephone communication. Now the Nazi terror was backed by the government; truckloads of storm troopers roared over the country rounding up communists and other dissidents, torturing them in SA barracks.

At the Rhön Bruderhof, it was of crucial importance that men and women become decisive as to what attitude they would take. Eberhard spoke with some visitors, explaining the brotherhood’s calling. One married couple decided to leave.

Our calling is to represent the kingdom of God and the church of Jesus Christ, with all the consequences. This means that we feel our own love to Jesus, born of the personal experience of God’s love in our hearts, very deeply and gratefully, but that is not the main thing. For us the main thing is that God and his kingdom, in his coming world rulership, in his coming world peace, shall prevail among us in such a way that we represent this one cause over against all other circumstances, conditions, and relationships. As a result we come to a powerful and decisive opposition to the world around us. This also means opposition to the state, which has to be maintained by violence and the military. It has to defend private property with violence and enforce the law to uphold its power.

We do not withhold our respect from God-ordained government (Romans 13:1). Our calling, however, is a completely different one; it brings with it an order of society utterly different from anything that is possible in the state and the present social order. That is why we refuse to swear oaths before any court of law; we refuse to serve in any state as soldiers or policemen; we refuse to serve in any important government post—for all these are connected with law courts, the police, or the military.

We oppose outright the present order of society. We represent a different order, that of the church as it was in Jerusalem after the Holy Spirit was poured out. The multitude of believers became one heart and one soul. On the social level, their oneness was visible in their perfect brotherliness. On the economic level it meant that they gave up all private property and lived in complete community of goods, free from any compulsion. And so we are called to represent the same in the world today, which quite naturally will bring us into conflicts. This was also the case with the early Christians and the Anabaptists. We cannot put this burden on anybody unless he or she prizes the greatness of God’s kingdom above everything else and feels inwardly certain that there is no other way to go.16

* Alfred Hugenberg was the head of the Nationalist Party, a rightwing party that initially supported the Nazi party but was ultimately taken over by it. Franz von Papen had been appointed Reichskanzler by Hindenburg in 1932 and believed Hitler could be controlled.