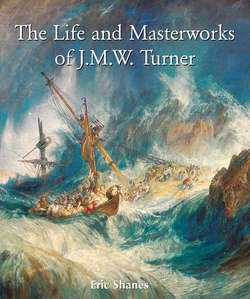

Читать книгу The Life and Masterworks of J.M.W. Turner - Eric Shanes - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface

ОглавлениеJ. M. W. Turner, Lake of Lucerne, from the landing place at Fluelen, looking towards Bauen and Tell’s chapel, Switzerland, signed on barrel to right JMWT, c. 1810, exhibited R. A. 1815, watercolour over pencil with scratching-out, stopping-out and gum arabic in original frame, 66 × 100 cm (26 × 39 inches), Private Collection.

We gaze across a vast lake surrounded by huge, gleaming mountains. In the distance a heavy storm has moved off, leaving in its wake an atmosphere brimming with moisture and a world beginning to steam in the brilliant dawn sunshine. Not far away a group of travellers which has been drenched by the storm while out on the waters is alighting from a small ferry boat, their belongings and cargo strewn across the beach. On the right a girl sniffles into a handkerchief, possibly crying over the spilt milk that lies before her but more probably because her recent, chillingly damp experience has given her a head cold. Further off more boats approach, while near the very tip of the headland in the far distance to the right can just be made out the chapel first created in 1388 and rebuilt in 1638 that was dedicated to the memory of the Swiss fighter for liberty, William Tell.

Such is the immediacy of the image that one might be forgiven for thinking that it was made on the spot but that was certainly not the case. Instead, it was conjured forth from a very slight pencil drawing made by the lakeside, plus an amalgam of memories and observations that were not necessarily gleaned at this place. Above all it stemmed from an imagination that was powerful, passionate and prodigious. Nobody knows exactly when Joseph Mallord William Turner created Lake of Lucerne, from the landing place at Fluelen, looking towards Bauen and Tell’s chapel, Switzerland but it probably dates from around 1810, and thus some eight years after the twenty-seven year old artist had visited Switzerland. The work was developed in the medium of watercolour, a vehicle that before Turner had usually been employed far less expressively to communicate the dry facts about a place and its occupants. Because of the large size of the drawing, plus its combination of spatial breadth, intricate detail and wide tonal range, it might easily be mistaken for an oil painting. Such a misapprehension would only be intensified by the ornate gold frame that first enclosed the image and which has remained around it ever since. Turner certainly intended to mislead us in this way.

Would anyone need to be told that The Lake of Lucerne, from the landing place at Fluelen is a work of art? Does it not inherently define what constitutes such an object? After all, an image of this quality could not have been made by just anyone. Clearly it must have been formed by a uniquely endowed individual possessed of outstanding visionary powers, a high degree of insight into the appearances and behaviour of the natural world (which of course includes our own species), a total command of pictorial language, an absolute rule over the medium chosen for its creation and, not least of all, a feeling for both enormous breadth and tiny detail, the latter of which was amassed by means of an extraordinary degree of patience. In an age like our own, when cultural, social and political levelling and relativism (not to mention critical cowardice) permits anything from a urinal to an empty room, some cuttings of pubic hair or an act of self-mutilation to constitute “a work of art”, a watercolour like the Lake of Lucerne, from the landing place at Fluelen still makes it clear that a true work of art presents us with something superhuman, exceptional and magical. Why these three things? Because any outstanding dramatic, musical, literary or visual work invariably draws upon powers far beyond our own to lift us onto a plane that is more imaginatively powerful, emotionally thrilling and intellectually stimulating than the mundane one we normally occupy. Like many of Turner’s other works, Lake of Lucerne, from the landing place at Fluelen elevates us to that level most ardently and easily.

It was with watercolours demonstrating exceptional qualities that Turner first attracted public attention in the early 1790s, before he had yet turned twenty. As time went on, and as he developed his abilities as an exceptional oil painter, draughtsman and printmaker as well as a watercolourist, so too appreciation of his works flourished, to the extent that by 1815, the very year in which Lake of Lucerne, from the landing place at Fluelen was first seen publicly, an anonymous writer could term the artist “The First Genius of the Day”. In an age of creative giants such as Beethoven, Schubert, Goethe, Byron, Keats, Delacroix et al., that was quite some compliment. Certainly it was not an overblown honour, for Turner does stand tall within such company. Moreover, his popularity has rarely diminished, even if his prices at auction did somewhat decrease between the 1920s and the 1960s. However, since then they have more than bounced back, to the extent that today his works regularly elicit huge prices at auction (as can be witnessed with the Lake of Lucerne, from the landing place at Fluelen, which fetched almost two million pounds when sold in London in July 2005). And beyond the marketplace there are vast numbers of art lovers whose admiration for Turner only grows by leaps and bounds. They simply cannot have too much of him. In 2000–2001 the present writer organised an exhibition of many of Turner’s finest watercolours at the Royal Academy of Arts in London in order to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the painter’s death in 1851. Almost 200,000 people flocked to the show during its eleven-week run; at peak times it could take up to four hours of patient standing in line to obtain entry. Moreover, an even more striking assertion of Turner’s popularity was provided early in 2007 when Tate Britain publicly appealed for funds to purchase the 1842 watercolour The Blue Rigi: Lake Lucerne, sunrise that is reproduced on page 226 below. Of the £4,900,000 sterling that the museum needed for the acquisition to go through, £300,000 was sought directly from the public. Within just five weeks, admirers of Turner both within and beyond British shores had sent in almost double that sum in a ringing endorsement of the need to purchase such a drawing for a major public collection. Clearly, a great many people still recognise a wonderful work of art when they see one, and feel it belongs to them, rather than to some rich private collector.

Yet this is not to say that the acute responsiveness to Turner has not been without its problems. Even in the artist’s own day there were many who could not stomach his daring. During the 1800s and 1810s he was severely criticised for his use of white, so much so that both he and other painters who followed directly in his footsteps were dubbed “the white painters”. Moreover, from the 1820s onwards the artist’s predilection for yellow led to many jokes and snide remarks being made in the newspapers about his pictures. When Turner combined intense yellows with fierce reds, blues and greens, journalistic comparisons abounded between his paintings and food, particularly scrambled eggs and salads. Then there was Turner’s dissolution of form within areas of intense light (which, in his late works, often took over entire images). Many members of a public that was becoming increasingly habituated to the intense verisimilitude of Pre-Raphaelite painting and/or Victorian bourgeois realism could not comprehend what was going on in a late-Turner canvas or watercolour. Even collectors who had previously lined up to purchase the latter kind of works found many of the artist’s late Swiss drawings difficult to understand and wouldn’t buy them.

J. M. W. Turner, The Founder’s Tower, Magdalen College, Oxford, 1793, watercolour, 35.7 × 26.3 cm, The British Museum, London, U. K.

J. M. W. Turner, Venice: the Mouth of the Grand Canal, 1840, watercolour, 21.9 × 31.7 cm, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, U. S. A.

Such problems of visual comprehension could be greatly compounded by Turner’s lifelong construction of covert meanings. Only an entire book given over to this subject (such as the present writer’s 1990 publication, Turner’s Human Landscape) could even begin to do it justice. But it will suffice here to state that for Turner, landscape painting was a vehicle for expressing his responses to the immense variety of human experience, not just a means of stating his recognition that the world around us is a beautiful or a terrifying place. One way of doing that was to resort to associationism, the creation of chains of ideas by means of visual linkage, metaphor, simile and punning. Because Turner was endowed with an innately complex mind, his meanings are necessarily complex. As a result, they have often mystified his devotees. But to grapple with those meanings must be attempted, for if we ignore them many of Turner’s works remain opaque. In these pages such drifts of meaning will certainly be tackled. For far too long, empty explanations – such as ascribing Turner’s images wholly to a supposed awareness of the “sublime” – has proven a lazy way of avoiding the necessity of taking on the many significations of meaning that were certainly set in motion by the painter.

The failure to understand Turner’s meanings has not been helped by changes in taste either. Thus the gradual emergence of a predilection for French Impressionism led to the widespread belief that Turner was “the First of the Impressionists”. That this misapprehension is now so deeply instilled is perhaps understandable, for it was fostered by many supposedly knowledgeable art critics throughout the twentieth century, and it continues to be propagated. We shall deal with such a false claim below but here it will suffice to emphasise that Turner was most certainly not an Impressionist, even if some of his canvases clearly did exercise a positive influence upon Monet and Pissarro. And then there was Turner’s appropriation by the American Abstract Expressionists. In 1966 he was granted the rare honour for an artist born in the eighteenth century of being accorded a one-man exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The basis for that show was the entirely false premise that, deep down, Turner had really wanted to be an abstract painter but because of the demands of his age, he could only attain that end by disguising his abstraction with the empty trappings of representation, introducing a few meaningless figures here, an occasional boat there or some curious-looking fish elsewhere. Most Turner scholars now think that this was just not the case, for a large body of evidence demonstrates that the painter’s “abstract” images were either underpaintings that were never subsequently overworked, or studies for highly-representational images that derived from them. In any case, throughout his life the painter had undoubtedly been a representationalist, so why would he have developed into an opposite kind of artist in his later years? Given his writings, it appears far more likely that in his late works Turner simplified his shapes and raised the pitch of his light to a blazing level in order to project an ideal, platonic world of form and feeling. The arrival at such a realm through art had certainly been advocated by the theorist on painting who most powerfully influenced Turner throughout his life, namely Sir Joshua Reynolds. And that move onto some higher and more profoundly true reality than the one we occupy was surely what Turner the visionary was attempting to depict as he neared his end, not the emptying out of reality into meaningless abstraction.

Ultimately these widespread misapprehensions do not matter, for we each take from a work of art just what we need from it; such is its utility. The world in which we now live understandably forces us to seek beauty in order to offset all the ugliness that increasingly surrounds us. Turner provided that loveliness in abundance. He also furnished us with so much more: the fearsome power of nature, its ineffable peace, its immense grandeur, its underlying behavioural constants and, just as much, all the doings of man. In these pages alone the latter includes trading, carting, sailing, whaling, imprisoning, electing, gawping, scurrying, celebrating, bickering, squabbling, building, destroying, fighting, suffering, drowning, dying and mourning. Here was a painter who stood firmly within the modern industrial epoch in which we now all live and still perceive the last vestiges of the pre-industrial world that lingered all around him. Among many other things he made it his business to capture both the old world order and the brave new world, and to do so with enormous invention and finesse. That is surely one of the reasons we so treasure his works and why we will probably always do so. Turner pointed towards the past, the present and the future. In that sense he was truly timeless.