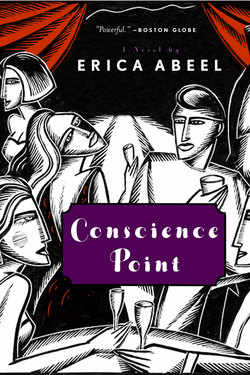

Читать книгу Conscience Point - Erica Abeel - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 2 The Three Doors

ОглавлениеBailas como gringa. Ma, the merengue’s just a two-step: drop the hip, drag your leg at the same time.” Laila demonstrated, high, round ass switching, Latina cool. She wore ripped jeans and a dish-rag tee, the uniform favored by private-school kids and crack addicts. She turned the salsa to ghetto-blaster volume, and they hit it again, Maddy, a tad shorter than her daughter, melting into the moves. “Eso es! Way to go, Ma. . . .” As they rounded a standing lamp, Maddy’s toe caught on the Persian carpet; carrying Laila with her, she flopped onto the sofa, both of them laughing.

Laila’s body had all the heft of a finch. Along with the merengue, she’d acquired a parasite from her Latin travels; insisted she was cured, but why should a mother stop worrying?

Maddy lowered the music and ogled her newly redone living room. The parlor level below a monkish space with two Steinway grands—but here on the second floor, a paean to Olde English: window seat in a William Morris greenwillow chintz; the new “heirloom” Persians Nick teased her about. Her flame-stitch wing chair, acquired in the lean days from Goodwill and reglued—talismanic. When they weren’t together at the Point, Nick shuttled between here and a studio near his office. They enjoyed days off; from long habit each needed solitude. Nick had clocked a twenty-five-year marriage; she’d lived with Marshall for six—yet till they found each other, essentially they’d both been alone.

“Lou, let’s teach Nick the merengue next weekend,” Maddy said.

Laila slid down on her tailbone, coarse reddish curls fanning around features set a tad close in her face. The greenish eyes and caramel skin turned heads (while Maddy, slightly famous, was edging toward invisible). Her enchanting smile, like aromatherapy, made people around her happier in their skin. “Uncle Nick dance?” Laila pursed her pillowy lips. “No way.”

“Honey, he’s not such a stiff.”

Laila loved Nick—now that her loyal heart had forgiven him for displacing Marshall. She was comically protective, coaching Nick, a WASP relic, in modern folkways. Last summer she’d gone to Nicaragua to help build a school—in a village menaced by cholera—and returned to the States with a calling: to photograph the Third World’s poor in the manner of Sebastião Salgado. This summer she was headed for Juárez with a photojournalist to document the fallout from global capitalism. The child had been born with a social conscience the way she herself had with perfect pitch. . . .

Maddy sank into her wing chair; four A.M. Europe time, and she was caffeinated with fatigue. Her eye wandered over a weekly lying open on the coffee table. She made out the byline Jed Oliver. Tenants’ lawyer, unlikely mix of social climber and wolfman—and her daughter’s fortyish boyfriend. Laila had started late, clinging longer than quite normal to Babar the elephant king and a battered picture book of Greek myths, dreaming and playing solitary games among the gardens and crumbling statuary encrusted with lichen at Conscience Point.

“Lo, something I wanna talk to you about.”

“Oh, brother.” Laila slid down on her neck, legs akimbo, caramel knees poking through her jeans. How had this child gotten so thin?

“Of course we all admire Jed Oliver for the cases he takes on, but isn’t he a little—”

“Old for me.” Laila always a beat ahead. “Like who gives a shit?”

Maddy startled. Laila never took this pit-bull tack; she was more Ferdinand, dodging the picadors to sniff the flowers. Maddy heard her friend Sophie: If a guy’s white, employed, and dates psychiatric social workers, he thinks he’s exempt from AIDS, so why spoil the moment fumbling for a Trojan. “Uh, y’know, Jed’s run through an awful lot of women,” she said.

“Ma. No one does unprotected sex anymore.” In case Maddy doubted the existence of telepathy. “Look, he’s just a guy I hang with, I’m almost nineteen, I know what I’m doing. Give it a rest.”

That un-Laila harshness again. “Lo-ey, it’s just . . . I don’t want you to associate love with unhappiness.”

Laila’s gaze turned inward like a child’s beneath her straight black lashes. As when she’d first learned about body bags, when Maddy had taken her—mistakenly; unforgivably—to All That Jazz. Peeling off the couch, Laila loped to the mantel and scowled at the photos in ornate silver frames: herself smiling gap-toothed from a rowboat in Central Park; standing with Nick, suited up and beaming from the dazzled slopes of Bromley—scenes of ordinary family happiness. Though Laila’s passage into Maddy’s safekeeping had been anything but ordinary. The official story: Maddy had adopted her from a foundling home in Rabat, Morocco, a star child in a carton grasping a silver rattle—a story about as credible as Babar.

Laila toed the copper fire fan with her black hightop. “Mom, there’s something I gotta tell you.”

“Oh, brother.” Echoing Laila as a joke, yet her throat tightened.

“The thing with Jed—it’s just not where I’m at anymore.” A little huff of exasperation, an Ashcroft tic. “I’ve decided to leave college for a while and go work in Guatemala.”

Maddy pitched forward in her chair. “Drop out?”

“Arghh”—Laila favored comic-book expletives. “No, take time out. Anyway, your view of Brown is totally unreal. Kids are like, Hello, who’s Beowulf? They fly the Concorde to Paris, they do lines in the dorm. And there’s this new course, a workshop on sex toys—”

“Surely you can find some worthwhile courses. Tara Gerson took time out from Yale and ended up in Oregon in a lesbian commune.”

“So? I cannot stand your homophobia.”

Maddy felt she’d wandered into someone else’s movie. Laila usually caressing and wise, with greater tact than the nominal grownups. She was nice even to telemarketers! You two are like sisters, people would say, not altogether approving. Yet recently, Maddy now recognized—her thinking slowed by fatigue—Laila had turned moody and irritable; she sometimes lashed out in anger at the least provocation. Since . . . before the vacation in France?

“Guatemala’s a dangerous place,” Maddy continued, skipping over eggshells. “Those coeds hijacked and raped. The nuns murdered in El Salvador.” Thanks to her daughter, she’d become an expert on mayhem south of the border.

“Third World violence comes out of the policies of the companies you and Nick invest in—they bleed Latin America dry. And lookit what’s going down right here. Building owners, like your buddy Amos Grubb, are fucking over the maintenance workers who’ve gone on strike, bringing in younger workers they can pay less. Someday they’re gonna raze the mansions on Midas Lane.”

Oh, brother. She shut her eyes and shook her head. Not at Laila’s outburst, which rather impressed her—she sensed it was camouflage. But for what?

“You don’t give me credit for being an adult,” Laila went on in a nicer voice. “I’m gonna work in a construction project in Lagunas, a village in San Marcos. And I’ve applied for a USIA grant to photograph the indigenous peoples for a show.”

Struggling for calm: “But why not finish college first—”

“Arghh, why must you boss everyone’s life?”

Sighing, Maddy rose, catching her image, haggard but svelte, in the night bay window. Well, the mother-daughter thing was famously toxic; she’d heard her friends griping about the resident bitch on wheels; she’d just been lucky till now. Suddenly she wondered if Nick found her bossy, too. And was she obnoxiously overscheduled, like those women who, Sophie joked, penciled in orgasms?

“You gotta trust me, I know what I’m doing,” Laila said enigmatically. Then her pale eyes glittered and she was close beside Maddy, hugging her, yet Maddy hung back, hands against Laila’s scary ribs. “I love you,” Laila said.

She felt this taut little body. Laila once smelled of unfinished wood from her bunk bed; now she smelled womanly and complicated. Okay, probably Laila had never forgiven her for Nick—that’s what was going on; with Marshall, Laila knew who came first. No matter that she’d bought her the Nikon F5 and created the darkroom on the third floor—Laila felt bought off. You did your best, and it wasn’t good enough. That seemed to be the deal.

She pulled Laila onto the window seat beside her. “Lou, let’s go away for a week, just the two of us. In September, for your birthday.” She’d shave some days off the trip to Ireland, even if Nick already groused it was too short. “We could go hiking in the Rockies. Remember that climb to Cathedral and coming down for lunch at the Pine Creek Cookhouse? I’ve never been so happy.” A girl’s happiness, gamboling and free, needing no tending like adult passion.

Laila flashed her lovely smile. “Remember those dogues?”—one of their invented words, which also included goofy love-names. “The ones wearing backpacks?”

“And the llamas? And the way the breeze flicks the silver underside of the aspens?”

Laila’s eyes clouded; she shifted away. “At this resort in the Caribbean they give the guests a choice of nine friggin’ pillows. And in Juárez the pepenadores forage for food in dumps and compete with dogs.”

That she could follow Laila’s logic didn’t help. Their connection crackled like a wire ready to short out. “So you won’t ever go anywhere nice?”

“I’ll go where I’m needed. I can have my goddamn birthday at the Point.” She jumped up, eyes darting around the room. “I’m outta here.”

Almost midnight, and she was leaving to meet Jed at that dive off Hudson where they’d just shot a dealer. Maddy stood in the middle of her lovely room, hands hanging. Well, here it was, delayed adolescence kicking in, plus a shitload of anger, and somewhere in the mix—Maddy tried to stifle that thought—a hint of hereditary damage?

Her fine reasons failed to satisfy. Something in her world felt out of joint. That bomb Nick had dropped about a baby. She was suddenly convinced he’d never mentioned any Nessa Trent-Jones before that evening in Nohant.

At the door Laila hesitated; turned and looked at Maddy. “I’m sorry. For everything.”

“What everything. What is going on here!”—but she’d vanished down the stairwell.

STRAIGHT OFF THE ELEVATOR, she saw the huddle like the folded wings of buzzards.

“Wait’ll you hear what happened while you were tripping through the poppies,” Sam said. White-lipped smile. “Charlie Unger’s out.”

Oh, shit, her dream of a boss. She’d caught the early rumblings of course, but in France managed to put all vexing thoughts on hold.

“Bern Conant’s our new executive producer.” Sam rolled his eyes at Maddy: Tried to warn you . . .

“Bern Conant, Lord help us.” Remembering last night’s cryptic message on her machine. Conant was the new breed of broadcast exec as high school dropout, postliterate, mesmerized by ratings. She leaned a shoulder against the cinder-block wall, feeling its texture of petrified cottage cheese through her blazer.

“Guess they’re grooming the local yokel for bigger things,” Sam said. “Welcome back, darlin’! Let’s hope our boy’s not dumb enough to monkey with your segment.” He steered her down the hall. “While you were away, Video Kitten badgered the powers to let her narrate a story on Hootie and the Blowfish. And in the rough cut of your Domna Scotti, she went with the least flattering shots. Watch your back.”

WELCOME BACK, INDEED. Maddy took refuge in her office, a bright, ordered place hung with photos: she and Byron Janis and other music luminaries; Laila and Nick on the beach; a treasured Laila painting from second grade of a mother and baby shark, “from your one and only daughter” . . . Jesus, Bern Conant. Station manager from local, dubbed by the industry “Conan the Barbarian.” He’d been associate producer on the morning news, and now, it appeared, the powers had judged him ready for his own show. Chronicle would beef up his bona fides before they handed him the evening news. Conan was known for looking at a story and taking out the best part. And when Martha Graham died, he’d assigned a piece on Martha Raye, the dentures queen. If they wanted to boost ratings by going tabzine, they’d found their man.

Heart leaden, she backhanded pitches and press kits into the trash. From one flyer leapt the name Anton Bers. God, they’d practically grown up together at Juilliard, she and Tony Bers. He’d been a prodigy and goofball who scorned scales and “practiced” by ripping through his favorite composers. Tony went on to win the Leventritt and join the exclusive preserve of pianists touring the world’s capitals—then, like many a gold medalist before him, tumbled from the heights. Injured his right hand, went the story; performed left-hand repertory for a while. Now the wunderkind had washed up in Monmouth, New Jersey, playing chamber music in the local Episcopal church. She sighed, engulfed by a world of regret.

Anton’s covering letter pitched a story about the current explosion of chamber groups. “Let’s talk soon.” She pictured the caption in a recent cartoon in the New Yorker: How’s never. Would never work for you?

Now, none of that . . . You needed a gauze mask to avoid catching the arrogance that was epidemic among New York’s players. And self-importance: marketing chlorophyll toothpaste for Procter & Gamble held the gravitas of religion. What she ought to do was invite Anton, for old times, to Conscience Point for a session of four-hands. And then they’d brainstorm how to spin his story idea. Of course now, under the new regime, she might be less of a player.

She’d somehow felt immune to the seismic shocks rocking broadcasting; eleven years on the show, she’d become a fixture; everyone was expendable, of course, but she perhaps less than others? She gave good value, Nick was right: concert pianist with an inside track on the arts who could write—plus poster girl for graceful aging with a devoted female following. Charlie rarely vetoed her ideas. He offered her TV’s most precious commodity: minutes. He’d become a lone holdout against the prevailing dumbing-down, going for think pieces and arts coverage for the literate. He’d made Sunday Chronicle the class act of network television, the cultural companion to 60 Minutes. And now? In one moment the palace Charlie had built could blow off like a heap of silt.

The world around her was growing curiouser by the minute. Maybe this the true onset of middle age, this loss of control and encroaching chaos.

She heard her friend, a correspondent they’d just cut loose: I figured I was going to spend my whole life in this business. This was home, Mother Network. But somewhere along the line I forgot that you’re always dependent on whatever exec is in charge. You could always be out on your ass, any day, easy.

You’ll work someplace else, Maddy had said.

Yeah? Who’s gonna hire a woman over fifty? You know, it’s like we get a moment out there. And if we’re lucky and smart, it’s a good long run. But then you’re out, the next generation moves in, and it’s someone else’s turn.

But suppose you were a rotten sport and declined to bow out. Supposed you wanted an open-ended run. An unlimited engagement. Pianists performed till they dropped; Shura Cherkassky played Carnegie Hall at eighty; the great Horszowski tottered onstage, half-blind. at ninety-eight. And what of prostate city over at 60 Minutes?

She thought, I’ll be damned if they’ll shove me offstage. I won’t move over till I fall over.

SCRIPT IN HAND, Maddy headed with her brisk step for Bern Conant’s office, the only one on the sixth floor with windows. (Cinder-Block City, they called CNB’s dreary quarters in a former Wonder Bread factory.) A blowup of Madeleine Shaye smiled from a bank of network notables on the wall. Almond eyes, alluring overbite—Israeli? Magyar? unbrandable; subtly subversive among the lemon-chiffon blonds. She passed the familiar sign on Sam’s door: “When I grow up I want to sit in a dark room and have people look at the back of my neck.” They would screen the rough cut of her piece—she, Sam, Juno, and the senior producer—and get Conant’s comments. Lop and shift graphs, turn the wrap-up into the lead . . . She’d always enjoyed this sculpting.

She harbored a special fondness for her Domna Scotti piece. The famed diva rose too young, too fast; sang too often, dropped too much weight. Then fell for a master of the universe, who dumped her for a Russian model. Now Scotti lived in relative obscurity, teaching and singing in regional opera. The story celebrated a life in music as its own reward and took a whack at the infatuation with a few superstars.

“Lessee, how long does she run now?” Bern mumbled.

“Four,” said Juno.

“Four?” said Maddy. “Last I looked it was seven—”

“We should get down to three and a half,” Bern said.

Old joke: one TV reporter to another: What’s your story about? Answer: About a minute thirty. “No way, material’s too good,” Maddy said.

“I don’t give a goddamn if it’s Christ resurrected—” Recalling whom he was talking to, Bern lifted his upper lip in a smile. “It is good stuff,” he said in a phlegmy burr, and popped in the tape.

Maddy shook her head in disbelief. It was just Domna scarfing pills, the failed suicide, kicking drugs in a London hospital, salvation ta-da! in the arms of a good man—and no music. “This looks like a telenovela, I’ll lose my credibility in the music world.”

The others stirred uneasily; imprudent to start life under the new regime by breaking an office commandment: Be a team player.

“I mean, for Pete’s sake, give us more than two bars of Traviata. This”—she was distracted by Bern’s cut-rate nose job, which tugged down his pale, watery eyes—“this would strain the attention span of a mayfly.”

“We bring in the war at two and a half,” he said. “That’s all we gave Bosnia.” Maddy detected a spasm of amusement in Sam’s long, whey-colored face. “We need something to goose this. Juno, we got some shots of the Russian babe? Trouble is, classical music—I mean, if it’s Pavarotti boinking his secretary, or the Three Tenors at Giant Stadium, great,” Bern went on, trying for the make-nice voice. He rewound to Domna getting coached by the great Tedarescu in Milan. “But this ‘floradora’ stuff.”

“Fioritura. Viewers like technical details, they feel they’re learning something.” She was distracted by a fresh menace: her standup displayed a jawline in want of whittling. She remembered Sam’s warning about her field producer, Juno, who appeared to subsist on daikon.

Bern lifted a paper off his desk, gave it a light slap with the back of his hand. “Gotta problem with this memo you wrote my pree-decessor.”

The others bailed.

“This whuddyacallit Ray—is he hot?”

“Arundhati Roy. She. An Indian novelist, very telegenic, tipped to win the Booker Prize in ’97.”

Bern’s pale skin pinked around the scalp. “And this”—he brought Maddy’s memo toward his face—“Martha Arg—?”

“Marta Argerich is arguably the world’s greatest living pianist. A force of nature, cancels more concerts than she plays, but audiences are fanatically devoted—”

“Yeah, really. But couldn’t you do something less exotic? Juno’s working up a story on girl rappers.”

So Sam had gotten that right, too. “How about a story on cabaret artists?”

Bern bobbed his head. “Good, good. Liza Minnelli?”

“Actually, I was thinking of the cabaret genre. Wonderful artists like Blossom Dearie, or Bobby Short; he’s been at the Carlyle for ages. Or Michael Feinstein.”

Bern colored deeper. “Listen, this is too exquisite, people in America don’t know from cabaret. They go to the Holiday Inn, they go to the mall, they listen to rock. Why not do—”

“Hootie and the Blowfish!”

“There you go!” A moment. “Actually, that’s already in the pipeline.” He looked at her uncertainly. “And not your kind of story.”

Okay, deep breaths. “Bern, this show has always been a class act, one of a kind. They brought me in to cover the arts without talking down. We have a loyal base—”

“And you’ve brought up the ratings and . . . you’re an essential piece of this.” He walked to the bank of windows and eyeballed her. “But we’re losing audience to Sunday Today. We gotta play to younger demographics and go easy on the highbrow.”

“Of course.” A long moment. “Well, too bad about the Times.”

“What’s that?”

“Yeah, ‘Arts and Leisure’ was planning a companion piece on Scotti, which would have publicized ours. But the way our story’s angled now . . .” She produced a regretful frown. Bern’s scalp went rosier. She could hear his thoughts clacking like teletype: Madeleine Shaye a T-rex, but she could get the “get.”

With masterly timing: “Perhaps we could find some middle ground with the Scotti,” she offered silkily.

ARMSTEAD’S, THE LOCAL recovery room. At least in Chekhov, she mused over a Virgin Mary, the barbarians whacking the cherry trees had charm. Her half-truth about the Times might salvage the Scotti. But in a fit of housecleaning, Conant could toss her like a yellowing antimacassar. The thought gave her dry mouth, as before a concert. She’d labored and schemed to assemble this dual package, an entrepreneur of herself. . . . Followed a husband to Fort Bragg, North Carolina; aborted her career as an Outstanding Young American Pianist. Abort careers is what women did in 1966, Maddy had told herself, relieved, almost, to fold into the pack.

After the marriage imploded, she returned to New York; accompanied ballet classes, pounding out Chopin waltzes and mazurkas—stop/start/stop/start—on brittle uprights; survived on Campbell’s pepper pot soup and cheddar cubes from art gallery openings. And woke mornings with the acrid knowledge that she’d missed her moment as a soloist, could no longer compete in the international competitions that shot a young performer into orbit. At thirty-two she’d outlived herself.

Then came Laila. She needed money now, for her Lou, who slept in a closet bunk in their basement studio next to the boiler, with its mystery leaks and view of feet passing like a TV “crawl.” It was the moment of The Women’s Room; the new feminist voices were shaking gold from the trees. Why not join the chorus? Over four years Maddy rose at five to work on a biography of her idol Clara Schumann. The rejections fattened a folder till one clairvoyant editor saw they could pitch Clara as an early feminist prototype, in a juicy ménage à trois with husband Robert and Brahms to boot. After the TV movie, Maddy bought the three-story brick redstone on Jane Street, the skinniest house on the block and a steal.

She was profiled on Chronicle with a group of the new feminist biographers. Afterward, Maddy convinced Charlie Unger she could do a better interview. He liked her performer’s poise and insider’s empathy—they’d just need to bland her down, lose the raccoon eyeliner and sound of Queens. He weaned her from the old print habits and taught her to craft a TV story, quoting Kuralt at her: “ ‘Listen to the pictures. Then write to them as you would write to music.’ ” He handed her the culture beat; she marveled that they paid her (and how!) for such fun. The visibility from Chronicle jump-started a modest concert career, which in turn swelled her prestige on the show—she invented synergy before it became the rage.

She signaled the waiter for another, gnawed by a fresh worry: Could she afford to leave Chronicle? Nick dipped deeply into principal, and theirs was a luxury born of expense accounts, fancy footwork—and her paycheck. Yet perhaps Conant’s arrival had opened a door. If she went ahead full-bore with the piano, hell, maybe she could rise to, say, the top rank of tier two. Nick felt buffeted by the same downmarket pressures as Chronicle—no more books, he fumed, just “publishing ops.”

She thought of Conscience Point, its crumbling facade and silent, closed-off rooms, its grounds choked with bittersweet, its becalmed air. Waiting to be tapped for some grand enterprise, to explode magically into life. Would Nick leap with her?