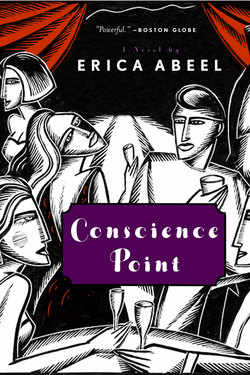

Читать книгу Conscience Point - Erica Abeel - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 3 Shadblow

ОглавлениеLa vraie vie n’est pas absente, mais ailleurs.

Real life isn’t absent, just elsewhere. . . .

—ARTHUR RIMBAUD

She’d balked when Nick wanted to buy the status car of the moment. But the Lexus, she would now happily concede, handled with a pliancy almost sexual. At the usual jam-up around LaGuardia, she launched on her inner clavier into the Spring Sonata, set for an August recital with Viktor Vadim; driving, walking, flossing, she always had a piece working itself out in her head. She ascended a scale crescendo, then dropped to piano subito. It was that wisp of a second just before the downbeat that gave Beethoven such verve.

As the cars inched along, she cut a look at the old neighborhood climbing the scraggly heights to the right. The Queens of semiattached stucco houses with Flowering Cherry, rose of Sharon, and plaster Virgins in front yards. And the rancid patch of discontent that was her parents’ lives. Butler Street, where she’d walked clutching her red tin lunch box with its cargo of bologna sandwiches wrapped in wax paper, its smell of turned milk. The evenings spiked with her teacher-father’s volcanic rages over “sloppy” playing. After losing a competition, she’d slept on the floor to punish herself; done exercises to strengthen her fourth and fifth fingers, all but wrecking the ligaments. She’d stood on the doorstep in her pajamas, bawling to the point of retching, the night Imre Horvath left for Regal deli to buy she couldn’t remember what and forgot to come home. Bawling till the lights winked on in the Gustavsons’ across the street. He’d left her only his rage for perfection: Thanks, Dad. Odd, she drove past here every weekend, oblivious to that cratered world.

Out on the highway the willows tossed a lime-yellow spume. She loved May, this excitable spurt in the year before summer’s tyranny of green. Closer to Riverhead a sharp eye could make out starry white blossoms. Shadblow . . .

She slid backward down the years and sat beside Violet Ashcroft in her fawn Mercedes. A roadster out of Gatsby, the dashboard made of lacquered, burled wood the color of strong tea. A Winston dangled off the driver’s lip, and she smelled of the car’s buttery leather and jasmine and sweat. She nervily sideslipped cars, shot ahead, abruptly downshifted, deaf to the honking; yakking and gesturing, a highway menace. See those starry white blossoms? They’re called shadblow. . . .

Thirty weekends a year, Maddy reflected, she drove to Conscience Point without revisiting that fateful trip. She’d turned unpredictable to herself. Since the holiday in France. Nick’s nonsense about babies, Laila acting out, her imperiled job—it was like three doors slamming, jarring loose memories, shuffling the coordinates of her known world.

She slowed, cursing, for a stretch of road work. A sign marked “Detour” with a flashing arrow directed all cars off the Northern State. She followed a thinning stream of cars along an unfamiliar road. Where were they hiding the signs for the expressway? She made a U-turn into a street abutting a stretch of tract houses, semibuilt and uninhabited; the builder must have lost his financing. The road ended squarely, eerily, against a grass embankment. As if the world it led to had evaporated.

On her right a ramshackle farm stand. She could make out faded white letters: “F—sh Straw—ies.” Her skin prickled. She had been here before, at this very spot. Over twenty-five, thirty years ago.

On that first drive out Violet had stopped at this stand—the farm itself long since plowed under. They bought a quart of the season’s first strawberries and ate them from the wooden box, the berries’ juice rouging their fingertips. Why did everything taste sweeter then? How foolish she and Vi would sound now, conjuring their lives as artists, disdaining marriage, frightened by their own bravado. For Laila and friends those battles would seem as ancient as the sacking of Troy.

Maddy sat with the motor idling, gazing at the ghost farmstand, and the past lay heavy upon her.

Come home with me this weekend. Violet’s cracked voice, a smoker’s voice, with odd catches.

Come with her just like that? The girl was nuts. “I’m preparing a concert.” Embarrassed by her status of music grind.

“You can practice at my place. Just come for one night—it’s only Long Island, for heaven’s sake. I’ll put you on the train Sunday. Or lend you a car.”

A car?

“You’ll play on the Bösendorfer! There’s one in the music room.”

In truth, she disliked the small sound of this pretentious Cadillac of pianos. But she was also drawn to this world where someone lent a car, to the danger surrounding Violet. . . . Could she break her routine this once? “I’d be a lousy guest, with my nose in the piano.”

“I would forbid anyone to disturb you. I’ll lock you in the music room, like Colette’s husband. And I’ll paint upstairs in my studio. We’ll be ruthless! Work all night if we like, and meet for breakfast.”

It astonished Maddy that this arrangement might appeal to anyone besides herself. She barely knew Violet Ashcroft, this only their second encounter. Of course everyone on campus knew Violet by reputation and sight. She was easily the most alluring girl of any class. She hadn’t much competition from the coeds populating Barnard in 1966: psych majors with pale, meaty thighs above knee socks, white cotton Lollipop underpants, Breck-girl pageboys. Rack up the As, then, to everything its season, land a Columbia premed with horn-rims from the other side of Broadway.

Maddy first sighted Violet on a crisp September afternoon of junior year by the dry fountain in front of Atkins. A new girl, a transfer student. She was arguing with a boy wearing chinos and a pink Oxford shirt, a preppy with the cameo profile of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Intrigued, Maddy stationed herself on the far side of the fountain. Sneaking looks at the chopped silver-blond hair, dark brows, scalded cheeks. She had a myopic stare that Maddy would later translate as unfettered self-absorption. She wore a yellow painter’s smock, green skirt, lavender stockings—like the Brangwen sisters in Women in Love. Her fingernails daubed a mortuary blue.

“Oh, for godssake, Christian, maybe you did leave Oxford on my account,” came her raspy voice. “Doesn’t make me your indentured slave, does it? And who asked you to leave anyway?”

“You did. You asked me.”

“What has that got to do with anything?”

Maddy’s cautious soul thrilled to the arrogance. She must find a way to meet this girl. . . . And now here she sat, amazingly, admiring the shad-blow from Violet’s snazzy car. Watching Violet’s hand, ringed in antique amethysts and sapphires, work the gear shift like a racer at Le Mans.

“I’m taking you to my favorite place in the world,” Violet announced as they careened off the highway. “I’ve brought us a picnic,” she added, shrugging toward a wicker basket on the back seat.

They drove into Islesford past a glassy pond patrolled by swans, past a white steeple and a row of elegant shops. A stop at Islesford Spirits for two chilled bottles of wine from Violet’s “old buddy.”

They turned down a road past a grey windmill. “Peniston Way’s more direct, but we’re taking the scenic route,” Violet said. “What a glorious spring. Look at that palette of greens.” She gestured around her, the car drifting out of its lane, terrorizing an oncoming pickup truck. Sunlight gilded pistachio-green leaves, boughs were festooned with parasols of celadon or pink. Along the road bloomed some kind of furze the color of dried blood. A roller-coaster rise—and there in the distance stretched Weymouth Bay, a dancing hive of light.

They dipped to a hollow and screeched to a stop. Violet’s hand with its gnawed nails cupped the vibrating gearshift.

“Green Glen Cemetery,” she announced moodily. Did the place actually radiate a moss-colored light? “Jackson Pollock’s buried here. Cracked up his car driving around sloshed. These roads have no shoulder. Best drive them sober.”

A moment. “My good brother is buried here.” Violet got out and disappeared over a hill. Maddy found her gazing up at a stone angel with a sweet, sightless smile. “Linton Ashcroft died in a tragic accident,” Violet said in a stagy monotone. “Went for an ocean swim and never returned. Till someone found a pelvic bone washed up on shore.”

“How horrible for him, for your family.”

“For some more than others,” she said oddly.

THEY WOUND DOWN Beldover Drive, its sides banked high with white dogwood. Turned right at a sign half-smothered in poison ivy: “Conscience Point,” and, in larger letters, “PRIVATE, TRESPASSERS WILL BE PROSECUTED.” The scrub oak bordering Wildmoor Road melted into a pine forest, a melancholy woods from Grimm; amazing to see towering trees hard by the sea. The afternoon sun angled a shaft of amber dust through the tall black boughs. Maddy sucked the resiny scent into her lungs.

“Over there’s the cabin where Mother keeps her true children—all thirty of them.” Violet waved carelessly toward a carriage road in the scrub oak.

“Thirty?”

“Her bird-children. Cockatiels. When she’s pissed she threatens to leave all her money to Audubon.” She downshifted with a vroom vroom. “Father died of a heart attack ten years ago—in the act, the clever man. With the carpenter’s son. After that Mother went to the birds. The rest of the infamous Ashcrofts you’ve probably heard about.”

Maddy vaguely remembered some Gothic tale about an Ashcroft fore-bear murdering his bride for her money.

“What about your people.”

Her people. After her father split, she’d come home from school to find her mother on the kitchen linoleum, foaming at the mouth from drinking shoe polish. Her mother’s relatives in Astoria gave her bed, board, and the word shanda to describe the disaster area named Horvath. . . . The tale somehow lacked the panache of the Ashcroft clan. “I use my mother’s name, Shaye,” Maddy said, midthought. “But I hate all that David Copper-field crap.”

Already, Violet respected her silences.

THEY CROSSED A low-slung bridge spanning a large channel: “Eggleston Bridge, death trap when it rains,” Violet said. “Aquaplane right into the water.” A covey of startled geese lifted, flapping and honking, into the air. Violet lurched onto a causeway bordered on both sides by blue-green bay and dotted with broken clamshells—“The clever gulls drop clams from the sky to crack them open.” Maddy blinked in the white light that seemed to boil down from a cataract in the sky.

Violet parked the car at the Point and they carried the wicker basket and a blanket down rickety wooden stairs to the beach.

“Mind the splinters and poison ivy,” Violet called over her shoulder. “Muthuh considers it vulgar to add modern improvements. Well! here we are, my favorite place in the world. I want my ashes scattered here.”

Violet seemed much taken up with death, but Maddy was too wonder-struck to hang on to the thought. She’d never seen a lovelier place: part New England, part Greek island . . . a place she recognized. Over to the right, a sand spit extended out into the bay, curving a sheltering shoulder around the water to form a jade lagoon. A sandy islet rose in the water a short way out. On the shore beyond, a stand for an osprey nest tilted at a rakish angle. All around stretched flats of lime eelgrass threaded by channels streaming molten silver in the sunlight. And farthest off lay a green island with dark stands of oak, receding in a lavender haze.

She’d been here before. The scene strangely called up a memory from childhood, of a painting on a biscuit tin of a watery, sun-struck Eden. She’d sit in the mean kitchen on Butler Street at the table covered in oilcloth and stare trancelike at the landscape on the tin, a golden land that seemed a signpost to a mysterious elsewhere that she longed to reach.

“This is all ours,” came Violet’s voice. She made a sweeping gesture at the land all around. Snapping her back. She herself owned nothing but talent, and planned to ride it far. What could Violet know about it? What did rich kids know about anything? She’d noticed something about the moneyed sorts who hung about the music world: they could do civility, but at stray moments out popped arrogance and entitlement, like a trained jaguar reverting to its natural savagery.

Violet was anxiously trying to decipher Maddy’s frown. “Here, let’s spread the blanket in front of this dune and break out the wine.” Violet opened the wicker basket and expertly applied corkscrew to bottle. “Gewürztraminer—bet you’ve never tasted any of this quality.”

She’d never heard the name. Violet freed the bottle from the cork, breasts bobbling through her gauzy flowered Hungarian blouse. Her penny-colored nipples peeked from among the green, blue, and red embroidered flowers. She lofted her glass, a figure from a pagan frieze.

“Welcome to Conscience Point, the first of many visits!”

The taste of the wine ambrosial. Violet set out a baguette, wedge of cheese, bone-handled knife on the orange, black, and green wool blanket. “Foie gras from Fauchon,” Violet announced, brandishing a jar. “You let it melt in your mouth.”

Afterward they lit Winstons and Violet sat knees clasped, head back, cigarette jutting from her mouth. Maddy cut secret looks at her grey eyes slanting down at the corners; spiky lashes, flared nostrils, hectic flush—created, she noticed, by tiny broken veins; the down above her fleshy upper lip. Her chopped Dutch-girl hair was fastened with a blue plastic barrette with a floral design.

“Here, your weed’s out.” Violet shifted to give Maddy a light off her cigarette. She held Maddy’s cigarette hand, then seized the other. “You must be very, very careful of these hands. I am in awe of talent. It’s the only thing I envy.”

Maddy was amazed to feel a tingling along her skin.

Violet released her hands, and sat cross-legged, staring out at the bay. “Oh, look, a cormorant.” Touching Maddy’s wrist, she pointed out the dark erectile head of a bird bobbing in the water before it dove for food.

The wine, the beauty of the Point, Violet’s admiration had lifted Maddy to a near-ecstatic state. The wheeling sun drizzled gold across the lagoon, the surrounding channels took fire. She wanted to wade into the blaze and dissolve in light.

“I see a mah-velous future,” Violet said. “You’ll be a concert pianist and play in the world’s capitals. And I’ll paint my little pictures. Of course I don’t have half your talent and don’t even try to disagree—I loathe false modesty.”

A moment. “You make it sound so simple,” Maddy said. “I see obstacles and sacrifice.”

“Oh, there’s always someone ordering you about. But when you come right down to it, who can really stop us?”

“Men. Husbands. If I place in the Queen Elizabeth of Belgium—big ‘if’—I’d play concert dates all over the world, I’d rarely be home. To make it as a pianist you need a ‘smoother’ to arrange tiresome details. How many men would do that for a woman?” She thought of her steady and, to date, only beau, an intern at Einstein. Leonard of Pelham Parkway. Kind, earnest, banal. His very name struck a dissonant chord in this place. “A husband wants dinner on the table at night—not an artist on the touring circuit. And once there are children—”

“Well, what are nannies for?” Violet said impatiently. “Those are just excuses.” She refilled their glasses.

Maddy gulped her wine, she whose acquaintance with drink was limited to the odd postconcert sherry. “We would invent our own way,” she said, catching Violet’s elation. “I mean, think of Edward Hopper. Who before Hopper saw the world like that?” Slurring the words. “The world of people who missed their lives.” Like her father, the onetime “keyboard lion” who ended up teaching “Für Elise” to grimy-kneed kids on Butler Street. Like her mother, who never forgave him, her sense of betrayal echoing off the walls.

“Missing your life—what could be worse?” Violet said. The wine had heightened her flush. “We do have precedents, pioneers in living—like Bloomsbury, a group of kindred souls living for art and love. Virginia Woolf, Vita Sackville-West. And Violet Trefusis—my distant cousin and namesake. The Happy Few have a way of f-f-finding each other.” Violet squinted at Maddy. “We could start our community with us. Today. This very moment.”

Maddy lofted her wine glass. “To art and love and the Happy Few.”

“To us. We’ll call it the Republic of Art. We’ll build it here at the Point, my swinish family be damned. This place was meant for artists, musicians. Look”—she gestured toward a meadow beyond the eelgrass—“we’ll build a little stage for outdoor concerts. I can hear the fiddles tuning up. . . .” Sudden grimace. “Y’know, I can’t picture Christian there.”

Maddy had forgotten all about Violet’s suitor at the fountain in front of Atkins Hall.

“After we’re married, Christian will want to live in Bedminster and do the unspeakable in pursuit of the uneatable—Oscar Wilde’s definition of fox-hunting. He’ll go to tailgate picnics at his Princeton reunions. With old classmates with straw boaters and red pants and redder noses. Summers among the stiffs at the Edgartown—Ed-guhtown—Yacht Club. And of course he considers my painting just a charming hobby. Sets me apart from the debs doing charity work for Islesford General . . . But the upside of marriage to the Generic Groom is the freedom. Christian would just go on selling bonds and hounding foxes and saying ‘Good-o,’ without noticing a thing.”

So: despite her high-flying talk, Violet would marry Christian, keep one foot safely anchored in the life she claimed to scorn. Maddy felt herself deflate. Violet was a bit of a fraud. Violet scrambled to her feet and stretched her hands to the sky. “Oh, why think about the old booby today? Let’s go for a swim before the green flies descend. It’ll be glacial but mah-velous.”

“I didn’t bring a suit.”

Violet flashed Maddy a scornful smirk. She pulled the gauzy blouse over her head and tossed it onto the sand and unbuttoned her skirt. It fell around her feet in folds of terra-cotta. She apparently did without underpants.

Maddy couldn’t pull her eyes off Violet, her broadish shoulders, round Indian breasts, horsewoman’s legs. Her beauty clothed her, she seemed the human extension of this place. She turned, a cello flare of hips and ass, sun glinting off the gold down on her back, and stepped over the pebbly sand toward the water. The tide had risen high on the beach as if coveting the land.

“Well, what are you waiting for?” Violet called over her shoulder.

More than the prospect of icy water, Maddy shrank at the thought of getting naked. With a backward glance to check for voyeurs, she quickly shucked her plaid Ship’n Shore blouse and stern unnecessary bra; stepped, tripping, out of her pedal pushers. She was slim-chested and hairy and bony-kneed, she would die of mortification. Alongside Violet, a pink-and-gold nymph, she was the dark, ill-favored changeling left in a basket on the farmer’s doorstep.

Violet was already striding, laughing excitedly, into the water. She splashed her arms and chest and face, gave a little yip, and plunged in.

Maddy mimicked her. The water delivered an icy smack. She dolphin-dove and stroked and kicked, and the sting subsided. Violet swam over. The water had slicked back her hair, turning it dark yellow, exposing her finely shaped ears. Their feet kneaded the khaki gloom below, water buoyed their breasts.

“Race you to the island!” Violet said.

She cut through the dazzled water in a racing crawl. Maddy paddled in her wake. The bay abruptly turned shallow where the dredged channel ended; her fingers struck bottom and she was knee-deep.

They sat on the putty-colored sand, legs drawn up, warming themselves in the sun. “Y’know, there’s a little beach over there I’ve never been to”—Violet looked over her shoulder toward the far green island. “It’s on the other side, you can’t see it from here. We must go there one day. To the other side of the island.”

She pointed out holes in the sand from which clams spit miniature geysers of water. Maddy was aware of Violet’s small tortured hand, beringed and nicotine-stained, lying beside her haunch on the sand. The wine, the bracing water and sun kissing her skin; Violet so close, her twin, almost touching, though they wouldn’t, of course—had tipped Maddy into a rapture roused only by music. She’d drunk too much Gewürzt—

“Oh, goddamn.” Violet stared across the water. “Wouldn’cha know.”

To Maddy’s alarm, a red MG crawled along the causeway above the dunes.

“I was hoping the dumb regatta would keep him busy all day,” Violet said.

A man in chinos and tennis shirt emerged from the MG and stood on the dunes looking across at them, hand shading his eyes from the sun. “Water nice and toasty?” he called, his voice staccato and mocking, uncannily close across the channel. Maddy tried to hunch her body out of existence.

“Come on in,” Violet called back.

“Think I’m nuts like you?”

“Crazier,” Violet shot back. She stood, raised her arms high in a pantherine stretch, looked around with studied indifference, and sloshed into the water.

Maddy watched in dismay, praying the interloper would drive off. He turned toward the squabbling in the osprey nest. The set of his head and ears like Violet’s. Then he reached into a shirt pocket and put on sunglasses and continued to watch them from the dune. Aviator glasses, she saw; so he, too, could make out details. How would she navigate the space from sand to water? Slither belly-down, a sea turtle returning to its element?

From the bay rose a silvery peal of laughter. “You mustn’t mind old Nicholas,” Violet called. “He’s used to a lot of nude prancing about. Oh, excuse me, how rude,” she added, treading water. “Nick, I’d like you to meet Madeleine Shaye.” She gestured at the islet. “Maddy, my brother, Nicholas Ashcroft.” A salute toward the bluff. Then she kicked for the mainland in her slow, powerful crawl, feet churning up an aqueous chuckle.

Maddy had made a decision. Abruptly she stood. Nicholas Ashcroft remained stonily facing her. She braved the gaze behind the sunglasses a beat longer than was quite necessary. Then waded calmly into the water.

After the burn of nakedness, she welcomed the ice. What kind of crazy family was this? They certainly played by their own rules. Today a milestone, she thought, eyes open in the green water: she’d been seen. Then came a sense of injury. Had she been one of his fancy debutantes, Nicholas Ashcroft would have had the delicacy to turn away.

She tread water for a moment, arrested by a new idea. She’d been almost as troubled “prancing about” naked in front of Violet as in front of her brother.

WHAT COULD HAVE prepared her for the house? She sights it first as they curve down a road hugging a grand sweep of lawn; catches it next through the red-black leaves of a giant weeping hemlock. Now it comes into the clear, a greystone apparition rising on the bluffs above Weymouth Bay against the copper sun. Before it stands a single shell-pink dogwood.

“My God, it’s a castle.”

An assemblage of greystone peaks and towers, an actual crenellated tower with four upthrust parapets, ogival windows, mullioned bay windows—a Gothic fairy-tale vision, pure folly. “Great-Granddad Gus kept building onto the place to house his huge, I’m sure despicably behaved, brood. He needed to do something with his money. Please don’t disappoint me by being awed.”

“And please don’t pull that snotty rich-kid number.”

Violet stops the car and stares straight ahead, the diesel motor idling loudly. “Listen”—twisting her head this way and that—“how can I explain? I’m so used to—fending off. Christian and the others. I scarcely know how to do anything else. But I want”—she sighs mightily—“I so want you to like Conscience Point.”

Like me, she means.

Violet looks through her for a long moment, beset by some idea, while Maddy takes in her dazzled gaze, her features of a young czar.

“Friends?” Violet sticks out a beringed hand.

Maddy squeezes the hand and closes her heart against Violet. She distrusts this instant unearned devotion. Distrusts the whole setup. The rich walk through the world collecting amusements, then toss them when they’re bored.

“Isn’t a neo-Gothic castle a little out of place by the sea?” Maddy says coolly. Eyes opaque. Yielding nothing.

“I’m afraid they got their geography rather m-m-muddled.” In her eagerness to please, the stutter Violet affects sounds real. “The house was originally designed to overlook the Hudson River, but then old Gus decided to build it on Long Island ’cause the sailing’s better out this way. Islesford’s founding fathers wanted it razed. It’s awfully Hollywood, don’t you think? A back-lot heap from Ivanhoe.”

She parks carelessly under the porte cochere. In the vaulted ceiling adorned with blue fleurs-de-lis, four faces grimace down from each corner. The bronze door to the entrance is flanked by two Roman busts. Violet tosses her beige duster over one.

“No one’s here, thank God. Probably tying one on at the Weymouth Yacht Club. Look, it’s all fake,” she says with a kind of disgusted admiration. She taps the door: “Bronze is really wood.” Flicks the marble trim with her nail: “Faux marbre. Whole joint’s really a wood-and-brick house faced in stone. There’s a faux finish on almost everything. Just like our family,” she adds with a joyless laugh. “But some materials are real, which really mixes things up good.”

They enter a dim reception room with rose silk walls and a bear rug. “Let me show you around so you won’t trip over some carcass on your way to the john.” Violet places her hand in the small of Maddy’s back in a manner distinctly masculine and steers her left. “Here’s the music room, your room. Muthuh calls it the conservatory.”

At the entrance looms a white marble winged Cupid sorrowfully taking leave of a reclining Psyche with raised arms. Maddy bends to read the inscription: “Love cannot dwell with suspicion.” Her eyes sweep over a rose velvet couch with carved mahogany back. Ceilings vaulted in gold—wood posing as stone, she guesses. Leaded stained-glass windows running floor to ceiling, depicting scenes with a phoenix or peacock. And parked by the windows, the Bösendorfer, ebony splendor belying its anemic tone.

Linking her arm through Maddy’s, Violet draws her into a library with green velvet chairs, a table covered in green felt, a bookcase with ogival moldings. The house silent but for the ticking of a giant floor clock in the hall, which makes the place seem all the more an unmoored stage set.

Violet bounds up a sweeping staircase with curved white marble banister—real marble, Maddy judges from its chill. “Come see my little pictures,” Violet calls behind her. They enter a Uffizilike gallery with barrel-vault ceiling hung with family portraits. In a section by the windows, Maddy recognizes paintings by Violet similar to ones exhibited at Barnard: rectangular slabs applied with palette knife of marigold orange, cobalt blue, cadmium yellow. Maddy admires Violet’s pastels of what she now recognizes as the idyllic beach they just left: greens in spring, russet in autumn. Violet is a gifted colorist, moving with ease from abstraction to landscape.

She stops before an oil painting lit by sun burning through the stained-glass window: a portrait of a young man of surpassing beauty, a Brahmin version of Pan. Fair hair, impudent nose, dreaming eyes, helplessly self-infatuated.

“That could be Lord Alfred Douglas, Oscar Wilde’s lover,” Maddy says.

“Linton? Yes, but Linny preferred women. Me at any rate. I painted him from a photo. He never would sit for me. Now he’s with the angels in Green Glen,” she says with sneering piety. “Left for a swim in the ocean one day and—”

Her eyes have a mad shine and Maddy wonders if all the Ashcrofts have a screw loose.

“Gotta watch the water in these parts,” Violet says. She taps Maddy on the shoulder and nods solemnly. “Last year a flood tide washed out Eggleston Bridge. A local contractor tried to cross it at night and drowned in his car. C’mon, let’s find you a room.”

She scoots up three small stairs to a pink-and-gold room. The bed’s carved wood headboard rises to a peaked dome and mimics a Gothic church. Above it an enormous lozenge-shaped window of pink glass. The dark-blue ceiling is seeded with gold—or are they silver—stars.

“Decor’s a bit overwrought, but I hope you’ll be okay here. Bath.” She nods toward a tub with claw feet. Maddy’s eye falls on a section of bathroom wall that seems to be spilling out its guts: plaster, sand, what looks like horsehair. “Oh, well, never mind thaht,” Violet says. “When you’re ready, come down for martoonies in the library. Unfortunately they might be here, though mother practically lives in the aviary. Maybe you’ll play something for us before dinner? That sublime piece you were practicing at the college . . .”

“Chopin’s Harp Étude.”

“That one, yes. Oh, would you play it again?”

Maddy frowns. “I don’t know. I’d feel I was earning my keep.”

Violet pauses at the threshold, fair hair and one grey eye glinting in a ray of sun. “He hates me, you know,” she says abruptly.

“Who?”

“Nicholas the Vain.”

“Why?”

“Because he’s as phony as the materials in this house. And I’m on to him. And he knows it.” She draws closer and narrows her eyes. Maddy aware of her musk through the flowered blouse of jasmine cut with BO; the down above her retroussé upper lip like milkweed silk. For a second she’s tempted to reach over and touch her finger to the downy place. Her arms hang leaden by her sides.

“Promise me something,” Violet says, scratchy voice pleading. “That harebrained fiancée of Nick’s should be a deterrent, but—promise you won’t go and fall in love with my goddamn brother. Like everyone else.”

WHAT HAD SHE SAID? And how would it have mattered?