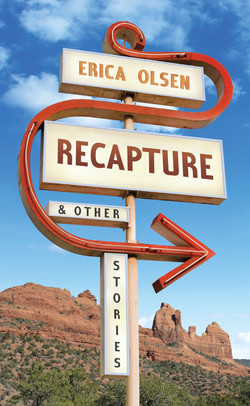

Читать книгу Recapture - Erica Olsen - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAdventure Highway

The approach to Moab from the south: the gigantic earth was Gulliver, strapped down by the grid of roadways and power lines. The mighty red rock suddenly hamstrung, all knees and knuckles. Tyler Swanson was driving in high dudgeon. Lately, dudgeon had become Swanson’s mode of being, though he tried to keep it at a low-to-moderate level. Not today. What had happened to Moab? It seemed all motels. On the north side of town, on the way up to Arches, he noticed people pedaling their bikes earnestly on a path that paralleled the highway on the east. If the path had been there before, and he didn’t think it had been, it certainly didn’t used to be paved. What had happened to dirt?

That ribbon of asphalt—it symbolized all that was wrong with the world. An ever-expanding list that included, among recent items:

Having been passed over for a job that should by rights have been his

Having to go on this trip without his girlfriend, Courtney

Swanson had a feeling that things in general had been made easier for people in general, but not for him. Regarding the latter item: Courtney had canceled literally at the last minute, as he was loading gear into the car. One moment he was cheerfully wrangling tarps and lawn chairs, the next her voice was buzzing into his ear the excuse that work was “crazy busy.”

He should go, she’d said—of course he should go.

And so he did, resolving to make the best of it. This time, this gift, this Swanson solitaire.

For solitude, Moab in April was, it seemed, exactly the wrong place. The presence of so many determined fun-havers was giving Swanson a jaundiced view of canyon country. Sweating in his vehicle, he waited his turn through the Arches entrance station. Through his lenses (amber, polarized) the heaps of rock looked like so much hamburger. He parked next to a planted island, which a spindly cottonwood shared with some bravely blooming globemallow. On the other side of the parking lot some people were taking photos of the cliffs adjacent to their RV. Maybe this was as far as they were planning to go. To the west, the cliff wall amplified the sound of traffic where the highway climbed out of town. Swanson heard the other inescapable sound, the confirming horn-honk of a car door locking, and groaned.

He’d wanted an adventure, or at least a getaway from the Bay Area winter of endless rain, but he struggled through the new visitor center. The building was very nice, depressingly nice, with its displays of faux sandstone, its lessons on the Entrada and Chinle formations and all the rest. A video screen set into an indoor cliff told Swanson Congratulations! He didn’t want to know what for. He missed old visitor centers with their quaint dioramas, their dusty specimens of taxidermy and such. The high-gloss treatment here was like a billboard for the real world, which needed no advertisement. It was right there! Out the window! Through the glass, the red cliffs shimmered, a little paler than they were in reality. Inside was a scaled-down version of Delicate Arch that Swanson didn’t want to walk through and yet there he was, walking through it. If the outside was hamburger, this sandstone mockup was pink slime, the processed beef that had been so much in the news lately. An indictment of our culture, Swanson thought.

What worried him most was just how many things seemed to him, these days, to be an indictment of our culture. He understood this for what it was, a sign he was middle-aged. Moab, at this time of year, was a veritable slide show of past and present fun he’d inexplicably missed out on.

For him there was the parking lot ordeal of sun block and sun hat and sun shirt.

He drove up the switchbacks of the escarpment, passing the Gather No Wood in Park road sign, whose medieval diction he used to alter to Gather Ye, then rhetorically inquire, What about wool? Is wool-gathering allowed? He passed it with a morose acknowledgment; there was something that used to make him smile.

At the trailhead Swanson overheard a vacation dad lecturing his vacation son, who was maybe nine years old: When are you going to start acting appropriately? Which, in context, may well have been a reasonable question, but Swanson glared at the dad, felt for the kid.

He felt for himself, having planned this trip buoyantly for months. But to face facts: Courtney had been questioning the travel arrangements. He’d proposed car camping—air mattresses and bathrooms, with plumbing whenever possible. Her reaction had been less than enthusiastic. He had to admit, now, she’d been giving him signals that she didn’t want to go. She was really more of a hotel girl.

He passed a geology class trip from somewhere ridiculously far away, Texas or Tennessee, giving a group thumbs-up to some roadside rock formation.

Spring break.

Swanson headed down the Park Avenue trail then ducked off it at Courthouse Wash. The academic year had not been good to him. He’d put in the time as an adjunct—freshman English, American Studies. Swanson had always been flexible, accommodating—and he had not been selected for an interview. That was a blow. He suspected his colleagues of looking askance at his methodology. His ecocriticism. Swanson had not published, not enough and not well enough; he’d put himself on the fast track to perishing. But he wasn’t dead yet! He wanted—he wanted—what? Utah, the geologic opera that used to make what he called (for lack of a better word) his soul feel as big and light as a balloon, wasn’t working for him this time. He looked at nature, and he felt nothing. Maybe it happened to everyone. Up the wash, where he’d hoped for tranquility, some boorish idiots, or idiotic boors—no doubt the same ones who’d let their kids scratch their names and the date across the rock of the main trail—were hallooing for the echo.

He hadn’t seen her for a few weeks, between his grading and her work schedule. That might mean something. Or nothing—people were busy sometimes. There had been a fight, though. He remembered her angry tears, the queasy feeling that still came over him when he recalled her revelation that she didn’t want to settle. He hated that word, settle.

“Settle down?” he’d asked.

“Settle.” She added, “It’s not fair to you.”

Yelling and clapping. Were they playing Marco Polo back there?

Swanson slunk away, continued on to the next pullout.

Where, next to an interpretive sign, a ranger was lecturing someone about hiking off trail. The trail itself was quilted with footprints. In his sun-blocking armor, Swanson plodded past a plethora of petrified hoopla.

And then, just like that, he’d had enough.

Enough! he said to himself.

He stuffed the hated nylon sombrero into a trash can and marched himself back to the car.

Before getting on the road he checked for a signal, checked for messages (he had none), then speed-dialed Courtney. He got voicemail. “Hey. It’s Tyler,” he said. “I was just. I was just wondering.” He laughed a little laugh. “When are you going to start acting appropriately?”

South of Moab, he was back in starkly empty country, the sage plain interrupted here and there by reefs and fins of exposed rock. Back before it was paved, this road was one of the country’s last adventure highways. He’d read that somewhere. That was before his time, of course, but adventure highway was what he wanted. Spaced out on open space, miles and miles of it, he almost missed the turn lane. He braked hard and without signaling swung right onto the turnoff to Newspaper Rock. The RV behind him sounded a bitchy toot of the horn. Swanson wished his fellow humans a fuck-you-very-much. This was exhilarating. Up ahead was a good pullout, with a sturdy pinyon-juniper grove for shade. He set off cross-country in a tonic rage—the ranger the trail the rules—then headed up a pink sand wash.

Out here, he could begin to face facts. What mattered here was life and death, rock and rainfall, the weird-looking cryptogamic crust that Swanson stepped considerately around. Not the romantic travails of a forty-year-old, the humiliation of another middle-aged breakup. Courtney was a few years older than he was, and in the back of his mind he’d assumed that when things went south it would be his doing. (A pretty grad student, a conference fling.) He’d been wrong about that. In her forties, Courtney had started to turn heads. And she was likely not to be there when he returned. She’d said as much the last time they got together, after the holidays. He just hadn’t wanted to hear it. The thousand-mile drive had given him ample time to turn her words into something ambiguous, something he could reasonably interpret in his favor.

He hiked hard, feet plowing the thick hot sand, until the voice in his mind quieted and he started to see what was around him, the beautiful world. A phalanx of cliffs glittering through his sunglasses, some unassuming low-growing yellow flowers. Goosefoot, he thought; the name came unbidden from some store of knowledge he’d forgotten he had. Feeling heavy, weary, he paused for water and a snack, then gave in to the gravitational tug of the earth. He sat himself down on some Late Triassic. (In relation to Swanson’s ability to identify strata, the visitor center had done its work.) A weatherbeaten juniper extended its limbs in fellowship. Some Mormon tea was growing in its shadow, gaunt yet luxuriant.

He stretched himself out on a bench of warm rock for a nap a collared lizard would envy.

He woke up in near-dark, shivering, and the water bottle had rolled away somewhere, and Swanson, who had wanted an adventure, cursed his stupidity.

How far in had he hiked? An hour or two, surely no more than that. Though there may have been some wandering near the end, some wandering concurrent with poetic musings and observings, during which time he may not have paid strict attention to his surroundings. During the time he took to assess the situation the last light vanished from the sky. He was in his technical shorts with the mesh vented panels, and the breeze rattled him. Why hadn’t he worn pants? He blinked against the confusing darkness.

His headlamp, of course, was in his car. (He remembered how this trip began, his pride in packing the gear just so. Once he’d gotten on the road it was a mess, of course, his good work undone. Why had he tried so hard in the first place?) The car was at the trailhead, and the trailhead—he did not know where it was.

He fumbled for his cell phone. He could use it to light his way.

He scanned the ground, gray and indistinct, for his own footprints, instructing himself: Don’t fall. That was the first rule of hiking, day or night. Swanson set his feet deliberately. Why had he worn sandals? They were like huge flopping rafts, ill-fitting, a stupid choice. His feet chafed, and almost certainly he had blisters. No, the first rule of hiking was Be Not Stupid, and he was violating it by hiking in the dark instead of waiting for daylight. Or waiting for rescue. Not that he needed rescuing. And if he did, how embarrassing would it be to be rescued while wearing technical shorts? He should never have let himself buy them.

Swanson trod stone and sand and cobbles, watchful, mindful of his limitations.

Soon enough, his eyes grew accustomed to the night. The bare rock reflected starlight. The night was full of strangeness. He heard a bird he didn’t know. Once he jumped at the appearance of a huge beetle that hovered in the air at knee level, clacking and swaying like some miniature robot drone. He had no idea where in the sky the moon would appear or in what phase it would be, but maybe if the world could pave a bike path from Moab to Arches it could give Swanson the moon. Swanson was not one acquainted with the night but it was remarkably freeing to stride along like this, unhoused. If he’d thought to stick a fleece into his daypack he was sure he could have ridden out the night in comfort. Why had he never taken up backpacking? This was the West, the wild and the free, the unfettered and confident. “You make a left turn at Albuquerque,” he proclaimed in the voice of Bugs Bunny.

Swanson fell.

Climbing up a small ledge he was pretty sure he’d descended on his way in, his sandaled foot slipped. He lost his balance and sat back in the air, landing awkwardly on his shoulders on the downslope, legs pedaling. Bassackwards was the word for it. It took a few tries before he succeeded in righting himself. Sand and juniper bits in his hair and down his shirt collar. He brushed himself off hurriedly, as if there were an audience to witness his ineptitude and discomfiture and so on. He felt for blood, found his phone, calmed his racing heart.

It was not the end of Swanson.

And then the moon, the kindly moon, came up and saved him, kept him from continuing up the ledge into God knows where. In the moonlight he could see his footprints waffling down the sandy wash—the sandals were new and the tread was clear. He followed them. After an easy walk, he saw the glint of moon on metal: his car.

How long until the car would have been noticed—until he was missed? Swanson felt weepy and indignant. Nobody cared where he was. He drove too fast, crossing the center line on the curves. Once he almost hit a rabbit as it raced in furred desperation across the roadway.

Single and forty, survivor of various ordeals, he turned back onto 191.

Monticello was a scatter of lights, the promise of a meal and a motel, civilization. Swanson felt suddenly, absurdly at home. He’d been there before. Monticello as in cellophane, he thought; not cello like the instrument or Thomas Jefferson’s house. He could see lights high up on the mountain road, someone else making the long drive into town. Hart’s Draw Road, it was called. The bloom of memory seemed wondrous to Swanson, as transient and lovely as spring itself. He slowed to forty-five, and saw the Maverik station on the north side of town.

Where the heck did that come from? he thought. It had not been there on his way up just two days before. Lights and angels and restrooms.

He pulled in across an admirably smooth curb cut, parked next to a full-size pickup with Arizona plates. The Maverik was obviously brand new, its expanses of red and black graphic and unspoiled. It was like a child’s toy just out of the package, life-size and dazzling. The asphalt was unmarked with wads of gum or sticky pools of spilled diesel. The pumps were a remarkable lineup, newly extruded from the plastic Eden machine and barely touched by human hands.

Swanson went in and found the restroom. He had never imagined that a gas station bathroom could be so pristine. It was a wonder.

In the mirror over the sink he found that he looked no better and no worse than anyone else.

The pickup pulled out while he was in the restroom, leaving Swanson the only customer in the store. He wandered the aisles. He admired the photo murals of mountains and canyons and the disembodied portion of spruce tree and the dummy kayaker suspended in midair. He admired the taxidermy. At the sandwich trough, the choice between turkey and Black Forest ham brought tears to his eyes. He picked up one of each. He picked up potato chips and tortilla chips and honey-roasted cashew nuts and a pickle in a vacuum-sealed bag with a picture of a cartoon pickle on it. He did not stumble, and no one knew what he’d been through.

At the register, he ventured a mild flirtation with the checkout girl. Jolted out of her reverie, she blinked at him in astonishment and wished him a nice day.

Swanson went out to pump his gas. From where he was standing, under the canopy, he could just make out the poster on the video rental kiosk—some movie in which attractive people met, then fell in love. All eyes and lips and hair, and a title whose lettering, at this distance, he couldn’t read. He made up his own title. Maverik: A Love Story. For the first time in a long time he felt that it wouldn’t hurt him to watch something like that.