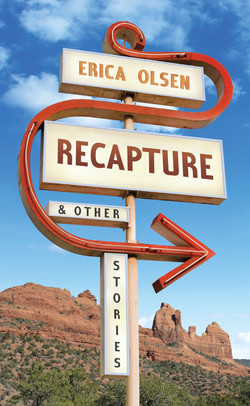

Читать книгу Recapture - Erica Olsen - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеEverthing is Red

I was walking over to the trading post to see Barbara, the trader’s wife. That morning, opening a can of peaches, I’d sliced into the palm of my left hand. The cut was deep, and close enough to the wrist to scare me a little.

The trading post stood at the bottom of a rough road that dipped down into a canyon. It was a small stone building in the lee of the cliffs, shaded by big cottonwoods. A car I didn’t know was out in front.

There were two men inside the trading post. One was the archaeologist whose camp was down the road from mine. I knew the other man by sight—one of the newspaper reporters come out from Denver to cover the Indian war. The reporter was sitting by the stove, drinking coffee and eating Barbara’s biscuits. His flannel suit was wrinkled, and some letters stuck out of the breast pocket. A red and yellow serape was draped around one shoulder and trailed down to the floor.

I thought there was an Indian too, one of the archaeologist’s mummies waiting to be wrapped in newspaper, packed in a crate, and shipped back to the museum in Chicago. It looked like the ones I’d seen before, sitting head to knees in the dim corner. But then my eyes adjusted to the light, and I saw that it was only some sacks of flour and a rug draped over the top.

The post carried groceries and hardware, blankets and tack. Baskets were propped on some of the shelves. Behind the counter, strings of silver and turquoise were bunched together, waiting to be redeemed. Dust was thick on some of the tags. Only a small part of it was dead pawn. Navajo rugs were laid across the counters and stacked on the floor against one wall. You could smell the grass the baskets were made of, and the smell of sheep was in the rugs. Set back on one shelf was a splendid black and white olla, an old cliff dweller jar.

The trader was away in Flagstaff but his spirit was everywhere—behind the counter, and in the lingering odor of his tobacco, and the creak of floorboards weighted by years of his footfall.

The trader’s wife was a tall woman with short brown hair fluffed into a wave. She unwound the cloth off my hand—I’d wrapped a piece of old shirt around it. Barbara had been a nurse before her marriage.

“How did you manage this?” she asked.

“Pure carelessness,” I said.

The men came close to look at the wound.

“He’ll need stitches,” the archaeologist said. He turned his own hand palm up and examined it in sympathy.

“I’ll get my bag.” The trader’s wife went into the other room.

The reporter said, “When I was starting out at the Times, I knew a guy who was bit by a rattlesnake.”

The “war” was over, Paiute Posey was dead, and the streets of Bluff and Blanding were safe again for whites. But the sight of my blood made his eyes go bright with excitement.

***

The trader’s wife came out of the back room with a doctor’s bag. She took some things out—antiseptic, a proper bandage. Her dress was printed with flowers. On her feet were men’s boots. I’d seen her wear city shoes with heels when she was getting ready to drive down to Flag herself.

The archaeologist was pacing the bullpen in a scholarly manner, with his hands clasped behind his back. From time to time he cut his eyes toward the olla. It was something over a foot high and round as a pumpkin, but with a flaring neck wider than a pumpkin’s stem, and two tiny handles low on the sides. Except for a band of white from the base to the handles, it was painted all over with zigzag bands of black. Whoever made it, they’d had a steady hand.

“I saw Burnett last week,” the archaeologist said.

“How is Jim?” the trader’s wife asked.

“He won’t sell.”

“Won’t he?” The trader’s wife poured hot water from the kettle into a pan.

The olla belonged to Jim Burnett, a rancher, and he kept it at the trading post. He said he was afraid of it getting broken out at his place.

“I was after him all last year for that olla,” the archaeologist said. “I offered him ten dollars. He wouldn’t take it.”

The trader’s wife smiled. “Maybe he knows it’s worth more.” She added some wood to the stove.

Burnett had found that pot on his land, rim and shoulders exposed after a late summer rain.

All over Utah, the pots were unburying themselves.

***

When the fire was crackling, the reporter addressed the room in general. “I’ve been up at Posey’s grave.”

Leaning up against the counter, the archaeologist shifted and cleared his throat.

“As a matter of fact, I went up there twice,” the reporter said.

The trader’s wife lowered the pan of hot water onto the table. She drew a chair up next to me.

To the reporter, she said, “Did you see the grave?”

“Well, yes, I did. That’s one good Indian.” The reporter waited for someone to laugh, but no one did. “We went up there after the marshal left. The marshal told us Posey was dead, but he wouldn’t say where he buried him. He promised the Indians he wouldn’t tell. But the men in town—they wanted proof.”

“He was shot, wasn’t he?” asked the trader’s wife. She washed my hand. With the blood gone, the cut didn’t look as bad. It was deep, but it looked clean.

“Shot in the leg, at the start of the war,” the reporter said. “Blood poisoning got him.”

“War?” the archaeologist broke in. “I wouldn’t call some stolen cattle and a shoot-out a war.”

The reporter shrugged. “The marshal left a plain trail all the way up Comb Wash. There was a photographer with us. He got his photos and then we buried him again. Decently.

“A couple of days later, the Indian agent wants to go out and see for himself, so we take him up there and he gets his portrait with old Posey too.”

The trader’s wife said, “It’s a shame he couldn’t rest in peace.”

“It’s more than a shame,” the archaeologist said. “It’s criminal.”

“What’s criminal? Digging up Indians?” The reporter gathered up the ends of his serape. “I hear you’ve dug up one or two yourself.”

The archaeologist stiffened. “The circumstances are entirely different. My work—”

“Hush now,” the trader’s wife said. “I’m trying to fix up this hand.” She unstoppered a bottle, and I winced at the smell of Mercurochrome.

The archaeologist had taken a step toward the reporter. “The marshal will hear about this,” he said.

“Why don’t you tell him?” The reporter laughed. His eyes went to the pretty olla on the shelf. “Is that for your museum or for your collection? I’ve seen what you do,” he said.

I’ve seen him too—him and his wife. A savory blue smoke comes from their camp. Behind it is the smell of the earth, sweet iron and rust and snow. The low, brush-covered mounds are pregnant with artifacts. The painted kivas lift their skirts.

The trader’s wife set the bottle of antiseptic down. She held up a hand to the archaeologist. Then she eyed the reporter. “You’ve got your mail,” she said, pointedly.

“I was just leaving,” he said.

***

The door dropped shut. We heard the car start. The trader’s wife put some gauze over my palm and pressed my other hand hard on top of it.

The archaeologist resumed his pacing. When the trader’s wife went to the counter where she had left the bag with the surgical needles and the thread, he asked, “How much does Burnett owe on his account?”

The book was open on the counter. The trader’s wife glanced at it.

“Twenty-two dollars and sixty cents,” she said.

The archaeologist reached into his pocket.

“Call it twenty-three even,” he said and laid the money on the counter. “I want that pot.”

She sighed. “All right,” she said. “But if Burnett takes it up with you—”

“I’ll be responsible,” he said.

He let himself behind the counter and took down the pot. He embraced it tenderly as he shouldered the door open. The bright sun knifed into the room. Motes of dust rose and fell around him, and there was a shock of green from the cottonwood leaves.

***

For the second time that morning I watched her monitor the closing of the door. At the sound of the catch she gave a little nod—whether of satisfaction or resignation, I couldn’t say. To my ear, the scrape of wood on wood suggested something conjugal.

She gave me the same kind of long, measured look she’d just given the door. Measuring me—as if to ask what I’d have done in all these circumstances—or maybe just measuring the distance between us.

The wood hissed in the stove, and the floorboards creaked, and I looked away.

The trader’s wife said, “There weren’t any letters for you this week.”

“I figured there weren’t,” I said. “I figured you would have said if there were.” I said, “That’s all right, Barb.”

“Still,” she said. “I should have mentioned it, earlier. I should have said.”

I’d come out to Utah with the oil company in ’21 and stayed on to do some prospecting myself. I set up camp a mile or so from the river. Later, I built a little house, a dugout, one room, that stayed warm and dry all winter. Next door to the dugout, I devised a root cellar. They looked fine, the root cellar and the dugout.

My wife was back in California all that time. Most of the letters I’d ever gotten in my life, and all the best ones, had come from her. But there hadn’t been a letter in a while. That was the day I stopped asking for one, the day I had my first clumsy thoughts about what else in life a man might want.

Down by the San Juan there’s a layer of limestone made up entirely of tiny shells. There’s a place where oil flows straight out of the rock into the river. Everything is red. The rocks, and the soil, and the thick fast-moving water in the river.

The trader’s wife resumed her work on my hand. The slim needle nipped—ten, twelve times. The ends of the threads floated up like spider’s silk. She took away the soaked pad of gauze and put down another. She wrapped a clean bandage around my wrist and across my palm and between my thumb and fingers.

“There,” she said. “There.”

Her hands were warm. They held mine for a moment. Under the bandages, I could feel the wet gauze, the blood still flowing.