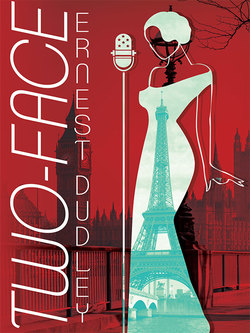

Читать книгу Two-Face - Ernest Dudley - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

She opened her eyes to meet someone else’s looking down at her. They’re a funny slate-grey, she thought drowsily, closing hers again.

“That’s it, take it easy,” a voice said.

There was something vaguely familiar about it. She felt too tired to remember, though, and lay quiet and still.

“Drink this.”

Gratefully, she sipped a glass of water held to her lips. It was very cold. It cleared the mists away from her brain. But the hammer beating at the back of her head still went on mercilessly.

She gave a little moan. Tried to lift her head. An arm slipped very gently under her, helped her sit upright.

“How’s that, now?”

She remembered now. The carefully pronounced French, with an obviously English accent. She opened her eyes, smiled wanly at the Englishman who had spoken to her in the airliner. He grinned at her, while she answered in English, slowly and distinctly:

“Thank you, that is much better.”

“Oho, speak English, eh?”

“My father was an Englishman—I like to speak his language!”

He noticed her voice had a curious huskiness in it.

“I see. And was your father’s French as bad as mine?”

“I am sorry, I did not mean to make you think that. But I knew you were English all right.”

“Well, we won’t bother about that now. And we’ll speak your father’s language. Still feeling a bit shaky?”

“It is only my head. It bangs a little.”

“Keep quiet, and the bang will soon go.”

He handed her the glass again and she drank. “That’ll help the headache on its way.”

She looked about her.

They were in a small waiting-room, and she had been placed on a long padded seat, with a rolled-up overcoat supporting her head. There was nobody else in the room. It was very peaceful after the noise before… Before…

Suddenly she remembered.

He took the glass from her. Comforted her with quiet strength. Calmed the turmoil of her brain, jangled thoughts from out of which the black headlines that had shrieked at her stood and danced their tragic dance.

She bowed her head in her hands and cried silently. Her anguish seemed to tear at the very roots of her heart. It shocked him with its intensity. Surprised him, too. He had not expected such grief from this slim, childishly young-looking girl. There was a hauntingly queer maturity about her grief which touched him deeply.

“This won’t do, you know. Listen. Listen to me.”

He sat and faced her. Watched the tears trickle through her fingers, and spoke to her very gently.

In a moment or two she ceased to weep and looked up at him. He pushed a lock of her mouse-coloured hair from off her face while she sat, her hands clasped tightly together, like a little child.

“You’ve got to pull yourself together,” he said. “I don’t know what poor Tallier meant to you—but you can’t alter things by tears. You must be brave. He’d want you to be that—wouldn’t he?”

She shook her head slowly.

“I don’t know. I don’t know. You see…” And she began to tell her story.

Right from the beginning. Hunched up there in that room whose silence only the faint hum of the arriving and departing airliners penetrated. Interrupted only by the appearance of a doctor, who saw she was recovered, and hurried off, she talked. Skilfully her listener prompted her.

Her name was Mitsi Linden, she said.

She told him how her father married her French mother after a whirlwind wooing. How he had deserted his wife soon after she was born. How this broken marriage had ultimately resulted in a wonderful bond of friendship and love between her and her mother. How, though they had to pinch and scrape to live, they were deeply content. They made no friends, for they were both shy and frightened of the world. But living for each other they had been terribly happy. They had drifted round France, then Italy, living in cheap pensions on the little money her mother had, then finally Switzerland and Zurich, a shabby, peaceful little villa outside the town.

Soon after her twentieth birthday that happiness ended with tragic suddenness. A short illness, and then…her mother’s dying wish she should get into touch with Tallier. He had been a loving, devoted admirer of hers, long ago, when her mother was a student in Paris.

That was all, the rest he knew.

“So there’s no one who can help you, now?”

“Nobody in the world…”

“Hmmm. It’s bad.”

He smiled at her, and stood up.

She watched him push his hands deep into his pockets and walk the length of the room and back. A wave of gratitude swept over her. She wanted to tell him how grateful she was to him for his kindness to her.

Somehow, she found it difficult to find words which would not sound trite and unreal. He is not an easy person to thank, she decided. He gave the impression he had done what he had as a matter of course. There was no fuss, no unnecessary words, or actions. Just a quiet method of dealing with everything.

No situation, she felt, would ever find him at a loss. There was a breadth about his entire personality, as well as the width of his shoulders. A roughness and a hardness which his present quietness seemed to emphasize.

Instinctively she was appraising him, his strength and his gentleness. He is rarely gentle, she told herself. Nor does he go out of his way to be charming, or nice. The set of his large, well-shaped head on his strong neck suggested a keen brain, but that of a man who disdained any subtleties.

She realized even the culminating tragedy of the last hour had not completely blotted out her inquisitive-ness. She plucked up courage and voice to ask his name.

“Sorry!” he apologized at once. “Here I’ve been cross-examining you from every angle, and you don’t know the first thing about me! I’m Larry Curtis—I write for the Courier—a London newspaper—”

Her eyes darkened.

“I hate newspapers,” she shuddered, remembering those dreadful headlines again.

“I know—well, forget all about ’em, or that I’m anything to do with them.”

He stood looking down at her.

“You’ve got to be sensible. Got to try and forget all that’s happened—not look back at all. I know that’ll be enormously difficult. But I want you to try hard. See?”

She nodded dumbly.

He sat down and faced her.

“Now, I feel a bit responsible for you, and I want to help you. Maybe I can, too.”

Her eyes were fixed on his face. In them such an expression of hope attempting to combat her tragic circumstances and her dark, utterly hopeless future. It moved him. Her helplessness seemed to reach out to him. Though she herself made no attempt to grab his sympathy.

Because she was so forlorn, because her dark eyes, big in her pale, tear-stained face, were so stricken. Because absolutely nothing about her was anything but a living picture of shabby human pathos, he knew he had to help her.

“I have two friends who live in Paris,” he said. “They’re brother and sister. Kindest, most understanding people in the world. Come along with me, and let them decide what’s the best thing to be done about you. Does that sound rather as if you’re a little stray dog?”

He smiled at her.

She shook her head seriously.

“That is what I feel like. Lost. But I cannot come with you. It would be impossible. You are a busy man, you cannot be worried by my troubles. Your friends, too. How can I ask them to bother about an utter stranger?”

“You aren’t worrying me, you won’t bother them. So put that right out of your head. Julia and Leo—my friends—will take care of you until you feel more able to take care of yourself. Glad to do it, and they’ll think up something for you to do, find a job for you, so you won’t be destitute in a Parisian gutter—which, so I’m told, is a most unpleasant place!”

She started to say something, but he stopped her.

“Why, you can’t do anything else, but follow my suggestion! Don’t you see? There was nobody here to meet you—I enquired about that…”

“You mean…?”

“Poor Tallier had too much on his mind the last day or two. He’d forgotten all about you. His own world crashed. He was ruined. If anybody else knew about your coming to Paris, well, they forgot, too. All this business has been a bolt from the blue—not only for you, but for everybody else, Henri Tallier as well.”

He rose. Her eyes remained riveted to his face. Her fingers were intertwined convulsively in her lap. He saw her lower lip begin to tremble.

“Mitsi Linden!”

Her name came sharply, and the hard note in his voice stopped the tears that were about to come. She gulped, and blew her nose.

“Another thing—you’ll find it difficult to leave Le Bourget without answering a lot of questions. There are several people outside there who are very anxious to learn why you fainted just now. I had quite a job to keep them away from you. Understand?”

“I could not bear to talk to anybody. It would be horrible. Oh, M’sieu—Mr. Curtis, what shall I do…?”

“Cut the ‘Mr. Curtis’, anyway. I’m Larry to my friends, and we’re friends. Secondly, put your hat on—unless your head’s still aching, and we’ll go and have tea with Julia and Leo. You’d like some tea, wouldn’t you? And an aspirin?”

She smiled. There was that in her smile which affected him profoundly. So full of courage and new hope it was.

“Yes,” she said, “I would like a little tea—and some aspirin.”

She stood up shakily. He took her arm, and she looked straight into his eyes with a queer frankness.

“Oh, thank you! I can never repay you. Never, never…” she whispered tremulously.

He tried to laugh, but a sudden tightness in his throat prevented him.

“I’m glad you think so well of me!” he said lightly.

Ten minutes later found them in a car, and on the road to Paris.

A silence fell between them. She was busy with her thoughts. Thoughts which went round and round in her head, and which she found impossible to sort out. They started with the Frenchman’s stare when he had pushed his newspaper aside to answer her question about Tallier. Then those words leaping out at her in huge black letters suddenly dwindling to nothingness and oblivion.

Then the hammering at the back of her head. Larry’s face when she had first regained consciousness, his voice, the import of his words. And, last of all, wonderment about where she was going, the two friends of his whom she was about to meet.

Everything seemed possessed of a curious dream-like quality. As if everything that had happened to her in the last hour had not really happened at all. She was only dreaming it. Presently she would wake up, and find herself back in Zurich.

“Or perhaps I’m dead,” she thought once. “Perhaps the aeroplane did crash, after all!…”

She gave a quick, panic-stricken glance at the man beside her. No! He was here, with her, protecting her, there was nothing to be afraid of. She was alive. She wasn’t dreaming. All the things had happened, and she was in this car with this wonderfully kind Englishman—going to have tea with two friends of his. Tea and aspirins, which would take away the hammering in her head.

Larry said nothing, the smoke curled up from his cigarette as he sat back wondering, too.

Paris, and the future drew nearer.