Читать книгу Ghost Stories and Mysteries - Ernest Favenc - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

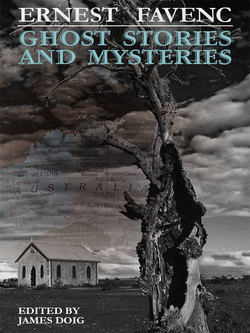

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION, by James Doig

Ernest Favenc (1845-1908) is arguably the most important Australian colonial writer of Gothic and supernatural fiction. The thirty one stories assembled here were first published in some of the most popular and important periodicals of the day and were read and enjoyed by a large audience. In his day Favenc was a prolific author of short stories and he wrote under several pseudonyms, most frequently Dramingo and Delcomyn.

Favenc is often described as a ‘romantic,’ in contrast to the literary realism of his better known Australian contemporaries such as Henry Lawson, Barbara Baynton and Edward Dyson. While it is true that he wrote many tales of mystery and the supernatural and his two adventure novels were certainly influenced by the popular romances of H. Rider Haggard, the strength of his work is drawn from his own experiences as a station hand and explorer in remote regions of Australia.

In his best stories, which were published in the first half of the 1890s, Favenc celebrates the mystery of the Australian outback. His characters—drovers and fossickers and explorers—range across an ancient landscape in which the supernatural can erupt at any time. These stories are written in a spare and uncomplicated style and Favenc attains an imaginative power that is unusual in the popular fiction of the time.

His tales are based on personal experience, of places he has seen and stories he has heard, enhanced by his interest in Australian history and legend. Thus, in “A Haunt of the Jinkarras” he adapts Aboriginal myth to his literary purpose, while “Spirit-Led” is based on the notion that seventeenth century Dutch sailors may have explored northern Australia. In this sense Favenc has something in common with the English tradition of the antiquarian ghost story exemplified by M. R. James and the American regional supernaturalists like Sarah Orne Jewett. Favenc weaves his tales from the stuff of Australian history and tradition in much the same way that M. R. James drew from his knowledge of British antiquity, or Jewett from the landscapes and traditions of New England.

This fictive naturalism sets Favenc apart from other colonial writers who dabbled in Gothic forms. Most Australian writers of the supernatural followed the model of the English ghost story, which had reached a standard form by the middle decades of the nineteenth century: a ghost interacts with the living in order to exorcise or ameliorate past sins or unrealised promises. A consequence of this limited dynamic is that the vast majority of ghost stories are conventional and unremarkable, and Australian colonial ghost stories are no exception—most are commercial offerings of little literary merit. Favenc, however, was able to extend the form mainly because he was conscious of the Gothic possibilities inherent in the Australian landscape and heritage. His interest in and knowledge of Australian history and legend coupled with his first hand experience of the remote outback gave him unique insights into the colonial experience. In stories like “Spirit-Led,” “A Haunt of the Jinkarras,” “The Boundary Rider’s Story,” and “Doomed” he modernised the Australian supernatural tale.

Part of this modernising is Favenc’s awareness of the interaction between the supernatural and the psychological. In several stories, madness, physical extremity and guilt are just as likely explanations for the events that transpire as the supernatural. In stories like “Jerry Boake’s Confession” and “In the Night” we are never quite sure whether we have passed that tenebrous boundary into the realm of the supernatural. This marks a maturity of conception, where the boundaries between realism and romanticism are not clear cut.

Perhaps Favenc’s greatest strength as a writer is his ability to create a feeling for the unknown. In his best stories there are no plot twists or convoluted explanations of events; the purpose of these stories is to tell us that strange things are out there and the lasting impression is that the outback has infinite possibilities and forms. This sense of the unknown is grounded in Favenc’s feel for the Australian landscape.

Favenc was a versatile writer who dabbled in a number of different genres: adventure, romance, humour, crime and the supernatural. His aim was to entertain and thrill, and he was attune to sensational plot devices and Gothic props that would entertain his readers: animated corpses, decaying bodies, madness, cannibalism, starvation, and so on.

He appears to have had a genuine interest in the occult, and some of his stories draw on occult themes and ideas, most notably “My Story,” “The Dead Hand,” “The Unholy Experiment of Martin Shenwick, and What Came of It,” and “Spirit-Led.” His adventure novels also reveal an interest in contemporary views about the lost continent of Lemuria and its association with theosophy.

A number of Favenc’s stories can be described as proto-science fiction. “What the Rats brought” is set fifteen years in the future when Australia is decimated by a plague and overrun by monstrous vampire bats from Asia. In “The Land of the Unseen” the invention of a machine allows people to see the invisible monsters lurking around them, while “A Haunt of the Jinkarras” involves the discovery of a race of primordial creatures.

Favenc was also adept at the humorous tall story, and his comic yarns still hold up well today; “The Ghost’s Triumph” is a good example. His early tale, “The Lady Ermetta; or, The Sleeping Secret,” is an amusing, if somewhat exhausting, parody of the type of convoluted tale that appeared in the Christmas number of the popular Penny Dreadfuls of the day.

Although he is an important writer who should be better known, Favenc was a professional who was paid by the word and some of his stories show the weaknesses that plague much popular writing. Many of his longer stories have overcomplicated and convoluted plots, clearly designed to fill a quota of words, and lack the precision of his most accomplished stories. Sometimes his plots are derivative and hackneyed; stories like “The Island of Shadows” and “The Haunted Steamer” conform to the standard mechanics of the contemporary ghost story.

Another negative aspect of his writing is the casual racism that permeates his work. This was a common enough attitude for the time, and in some respects Favenc was uncommonly sensitive to the plight of indigenous Australians; however, Aboriginal violence, especially in stories like “In the Night” is an ever-present reality for colonial Europeans and Aborigines and other perceived subordinate races like the Chinese are often disparaged.

Regardless of his shortcomings it is hoped that this collection will demonstrate that Favenc deserves to be regarded as a pioneer of Australian speculative fiction.

Favenc’s Life and Work

Ernest Favenc was born on 21 October 1845 at 5 Saville Row, Walworth, Surrey, the son of Abraham George Favenc, and his wife, Emma, née Jones. His father was a merchant by trade and his occupation appears to have sent him to different locations as Favenc was educated at Temple College, Cowley, in Oxfordshire, and in Berlin.

With his two sisters, Edith and Ella, and his bother, Jack, Favenc came to Australia while still a teenager in 1863. After a few months working in Sydney, Favenc moved to a cattle station owned by his uncle in north Queensland where he worked as a drover. He spent the next sixteen years in north and central Queensland working on stations, usually as a superintendent. His experiences as a drover in the outback provided the backdrop for a number of the stories in this volume, including “An Unquiet Spirit,” “The Boundary-Rider’s Story,” “The Ghostly Bullock-Bell,” and “The Red Lagoon.”

By 1871 he was writing fiction and poetry for the Queenslander, and in 1878, Gresley Lukin, the proprietor and literary editor of the Queenslander placed Favenc in charge of an expedition to survey a route for a railway line from Brisbane to Port Darwin. After travelling from Brisbane to Blackall in central-western Queensland, the small party set off northwest into the Northern Territory, discovering and naming natural features like creeks, lagoons and lakes as they went. Near disaster occurred in November 1878 when they were stranded on Creswell Creek due to water shortage, and they were forced to wait until rain replenished the water supplies. Their supplies almost exhausted, they reached the Overland Telegraph Line north of Powell’s Creek station in mid-January 1879.

Although the proposed railway line was never built, the expedition had a profound influence on Favenc’s prose and verse. Of his tales of mystery and the supernatural death from thirst occurs in stories like “Blood for Blood,” and “A Haunt of the Jinkarras”, and the threat of it is present in many other tales, while the country he explored during the expedition was used in stories like “Spirit-Led.” He also wrote several accounts of the expedition that appeared in newspapers and periodicals.

Favenc’s journalism and his successful land speculations in the Northern Territory in the early 1880s allowed him to marry and settle down in Sydney. On 15 November 1880, Ernest Favenc married Bessie Mathews, whom he had first met in Brisbane in the mid-1870s, at St John’s Baptist Church, Ashfield, Sydney. Bessie was born in Whimple, Devon, on 22 November 1860 and had come to Queensland in 1871-72 with her parents and eight siblings; her father, Benjamin, worked as a teacher for the Education Department. Ernest and Bessie had a daughter, Amy Eleanor, born on 24 September 1881, while another child was stillborn in late 1882 or early 1883.

At this time he was working as a journalist in Sydney, contributing substantial serial essays to the Sydney Mail on topics like “The Queensland Transcontinental Railway,” “White Versus Black,” “The Far Far North,” and “The Thirsty Land.” “The Far Far North,” which appeared in August and September 1882, described an expedition Favenc took from Normanton in far north Queensland to Powell’s Creek station in order to establish cattle stations. “The Thirsty Land,” serialised in November and December 1883, describes a journey to the same region made during March to May 1883. On this occasion Favenc was accompanied by Harry Creaghe, a business associate of Favenc’s, and his wife, Caroline, who left a detailed diary of the expedition. Leaving the Creaghes at Powell’s Creek station, Favenc continued north-east with two companions, exploring the headwaters of the Macarthur River, which they followed to the coast. They then travelled west, arriving at Daly Waters on 15 July. Soon afterwards, Favenc led a survey ship, the Palmerston, commissioned by the South Australian government to chart the mouth of the Macarthur and the Sir Edward Pellew group of islands in the south-west corner of the Gulf of Carpentaria.

The years following this flurry of activity were relatively barren, in terms of both writing and exploration. Favenc appears to have returned to Sydney where he experienced ill health, which according to Favenc’s biographer, Cheryl Taylor, could be a euphemism for the drinking problem that affected him intermittently for the rest of his life. It was not until the end of the decade that he began to write regularly again. The monograph Western Australia, Its Past History, Its Present Trade and Resources, Its Future Position was published in 1887, and resulted in a commission to explore the Gascoyne region north-east of Geraldton, which he undertook between March and June 1888. In the same year he published the magisterial The History of Australian Exploration, which has remained a classic of its kind and is still regarded as a useful source. Dedicated to the Premier of New South Wales, Sir Henry Parkes, the book reveals Favenc’s passion for exploration and adventure; he wrote in the preface that a complete history of the exploration of Australia can never be written as “[t]he story of the settlement of our continent is necessarily so intermixed with the results of private travels and adventures.” To some extent Favenc filled out his history in his fictional accounts of explorations into the outback.

The 1890s were Favenc’s most productive period as a writer, and his best tales of mystery and the supernatural were published between 1890 and 1895. By this time he had abandoned the discursive, over-complicated plots of his early short fiction in The Queenslander in favour of tightly controlled shorter pieces like “Doomed,” “A Strange Occurrence on Huckey’s Creek,” and “The Red Lagoon.”

The 1890s also saw the separate publication of two novels and a novella. The Secret of the Australian Desert was serialised in the Queenslander in 1890 before being published by the London publisher, Blackie & Son, in 1895. Like the best of Favenc’s fiction, the novel weaves fact, fiction and speculation. The Secret of the Australian Desert traces the fortunes of an expedition that sets out northward from Central Australia in search of fate of Ludwig Leichhardt’s famous expedition, which disappeared without trace. The novel crosses over into fantasy in its portrayal of a lost tribe of aborigines “wholly unlike any tribes known ever to have existed,” which draws heavily on contemporary interest in the lost land of Lemuria.

Similarly, Marooned on Australia (1897) is based on fact. As indicated by its subtitle, Being the Narrative of Diedrich Buys of His Discoveries and Exploits “In Terra Australia Incognita” About the Year 1630, the story speculates about the consequences of the wreck of the Dutch ship Batavia and the depredations committed by the mutineers. The first person narrator, Diedrich Buys, is one of the two mutineers who escaped execution and were instead marooned in North West Australia. As he battles to survive in a hostile land he comes across the Quadrucos, a race distinct from the Aborigines because its technology is too advanced and culture too sophisticated.

A novella, The Moccasins of Silence, was published by the Australian publisher, George Robertson, in 1896, and featured strange native shoes that were worn to attack enemies by stealth at night. The same shoes appear again in the late story, “The Kaditcha: A Tale of the Northern Territory” (1907).

During the 1890s Favenc worked mainly for The Bulletin, which was edited by J. F. Archibald whose preference for the unadorned bush yarn may have influenced Favenc’s style. Known as ‘the bushman’s bible,’ The Bulletin was an important newspaper that helped shape Australia’s national literature and published important work by Henry Lawson, ‘Banjo’ Patterson, Barbara Baynton, Miles Franklin and the cartoonist Phil May, in whose Summer and Winter Annuals Favenc would contribute.

A selection of seventeen stories published in The Bulletin between 1890 and 1890 was published in The Last of Six: Tales of the Austral Tropics (1863), the third volume of The Bulletin’s short story and verse anthologies. In 1894 the London publisher, Osgood, McIlvaine published Tales of the Austral Tropics, which dropped six stories from the earlier collection and added two others. A third collection of stories from The Bulletin, My Only Murder and Other Stories, was published by the Melbourne publisher George Robertson in 1899; this collected twenty four stories published between 1890 and 1895. Of the thirty one stories gathered here, six were published in The Last of Six: Tales of the Australia Tropics, and seven appeared in My Only Murder and Other Stories. A collection of verse, Voices of the Desert, was published in 1905.

Favenc was a part of the acclaimed group of Bulletin writers living in Sydney during the 1890s, and was a good friend of Louis Becke who was also a master of the short form, compared in his day with Robert Louis Stevenson. In 1898 Favenc joined the Dawn and Dusk Club, a group of Bohemian writers and artists and it was around this time that his alcoholism began to take a toll on his health again. Certainly, by the end of the 1890s he was less productive and there was a marked decline in the quality of his work, although between 1899 and 1903 he did write six stories for Phil May’s Summer and Winter Annuals with Gothic and supernatural elements. At that time, the annuals were edited by Harry Thompson, who preferred tales of horror and the supernatural.

By May 1905 Favenc was seriously ill in Royal Prince Albert Hospital, and later in year a bad fall that broke his thigh confined him to St Vincent’s Hospital. He died on 14 November 1908 in Lister Hospital in western Sydney.

Further Reading

Cheryl Frost, The Last Explorer, the Life and Work of Ernest Favenc (Townsville: Foundation for Australian Literary Studies, James Cook University of North Queensland, 1983).

Ernest Favenc, Tales of the Austral Tropics, edited by Cheryl Taylor (née Frost) (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, Colonial Texts Series,1997). This book collects the stories in The Last of Six and Tales of the Austral Tropics with a full scholarly introduction and critical apparatus.

Index of Stories in Ernest Favenc’s Short Story Collections

The Last of Six: Tales of the Austral Tropics (Sydney: Bulletin Newspaper, 1893)

The Last of Six

A Cup of Cold Water

A Haunt of the Jinkarras

The Rumford Plains Tragedy

Spirit-Led

Trantor’s Shot

The Spell of the Mas-Hantoo

The Track of the Dead

The Mystery of Baines’ Dog

Pompey

Malchook’s Doom: A Nicholson River Story

The Cook and the Cattle Stealer

The Parson’s Blackboy

A Lucky Meeting

The Story of a Big Pearl

The Missing Super

That Other Fellow

Tales of the Austral Tropics (London: Osgood, McIlvaine, 1894)

A Cup of Cold Water

The Rumford Plains Tragedy

A Haunt of the Jinkarras

Trantor’s Shot

Spirit-Led

The Mystery of Baines’ Dog

The Hut-Keeper and the Cattle-Stealer

The Parson’s Blackboy

A Lucky Meeting

That Other Fellow

Stolen Colours

Bunthorpe’s Decease

The Story of a Big Pearl

My Only Murder and Other Tales (Melbourne: George Robertson & Co, 1899)

My Only Murder

A Tale of Vanderlin Island

Blood for Blood

The Other Mrs Brewer

The Burial of Owen

The Red Lagoon

Tommy’s Ghost

The New Super of Oakley Downs

An Unquiet Spirit

George Catinnun

Bill Somers

Jerry Boake’s Confession

What Puzzled Balladune

The Story of a Long Watch

The Ghost’s Victory

The Sea Gave up its Dead

Mrs Stapleton No. 2

The Boundary Rider’s Story

The Eight-Mile Tragedy

The Belle of Sagamodu

Not Retributive Justice

A Victim to Gratitude

A North Queensland Temperance Story

A Gum-Tree in the Desert

A Note on the Texts

The texts of the stories in this collection are taken from their book appearance, for which they were often substantially revised, apart from those that saw their first and only publication in periodicals. The stories are arranged in order of their first publication.