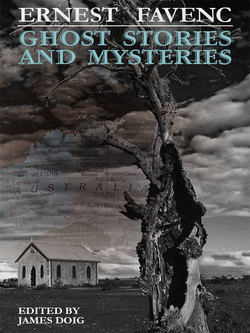

Читать книгу Ghost Stories and Mysteries - Ernest Favenc - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE MEDIUM

(1876)

Chapter I

The end of a dry season; the roads foot deep in dust; the grass, what was left of it, as brown as grass could be; the waterholes dwindled down into puddles of liquid mud—in fact, everything looking just as it always does after an Australian drought, as though it only wanted a fire-stick put into it to burn the whole concern up, and forestall the last day.

It was just sundown one day, during this desirable period of the year, when a traveller came cantering along the road leading to the Stratford station. On he went, raising as much dust as a marching regiment would in any other country, until he pulled up at the slip rails, dismounted, let himself and horse in, and wended his way up to the homestead.

The house he was approaching was the usual style of thing in the bush: two or three rooms, and verandah, with smaller huts scattered around. A very tall man was leaning against one of the verandah posts, smoking. He turned as he heard the horse’s tread, and welcomed the horseman by the name of Jackson. They shook hands, Jackson unsaddled his horse, and they went inside.

The tall man’s name was Starr, and he was the owner of the place.

Jackson handed him a couple of letters, remarking as he did so that he heard he was mustering, and had come down to look after his cattle if it was the case. “No,” said Starr, as he broke the envelopes, “I was only getting some fat cattle for Blatherskyte; I start to-morrow with them.”

“The beggers told me you were mustering down here, so I’ve had my ride for nothing. Luckily I am not very busy, for one can’t do much till we get some rain.”

“Well, I’m glad to see you down here. Tea will be in directly.”

“I will just rinse some of the dust off,” said Jackson, stepping into one of the bedrooms.

A trampling was just then heard outside. Starr went out, and was immediately greeted by name by one of the new comers—a young and good-looking man. The other was dark-eyed, with a black moustache, and rather a theatrical looking personage.

“Why, Starr, you are looking jollier than ever. I think you have grown even taller since I last saw you.”

“Glad to see you back again, Harris,” returned Starr as they shook hands.

“Mr. Haughton,” said Harris, indicating his companion. Starr bowed, and Jackson made his appearance, giving his face a finishing rub with a towel. Harris and he were old friends, so his greeting done, and Mr. Haughton having been presented for the second time, they went inside.

“What is the news from Blatherskyte, Harris,” said Starr, when they were all seated at tea.

“Any amount of gold being got by some; nothing by others. Mr. Haughton is one of the unlucky ones.”

The other two glanced enquiringly at the stranger, who had scarcely spoken as yet. He remarked that he had been up there for the last six months, that he went on to the field with money, and had now scarcely enough left to carry him off; so his luck had not been in.

“Everybody drunk last night,” said Harris, taking up the thread. “We were going to have a concert, but the singers got too drunk to sing, and the audience to listen—so that it was a failure as far as the melody of the affair went. You are going up to-morrow, did you not say, Starr?”

“Yes, I start in the morning, with some bullocks, and expect to get in some time during the next day. Any water at the twenty-mile creek?”

“Yes, enough to do you, and that is about all. When will you be back?”

“I intend to come straight back the day after I get in. I am going down to Imberwalla, to take down some gold I want to get rid of.”

“You will be worth sticking up.”

“Yes, I shall; for old Jawdon, the butcher, owes me for half of the last draft, which I shall get this time. I shall have about seven hundred, mostly in gold.”

“Well, that is not such a great sum, but many a man has lost his life for less.”

“I hope that is not going to be my case,” replied Starr; and after the usual bush talk about horses and cattle they rose from the table.

“Where is your old hutkeeper?” said Jackson, after the things were cleared away.

“I had a row with him this morning; he had been here too long, and was getting cheeky, so he went this morning. This man happened to be passing, and wanted a job, so he got the place.”

“I never did like that other fellow, he had an evil look about him,” remarked Harris.

“He was a very good cook,” returned Starr.

“Let us have a game at whist,” he said, rising. “Do you play, Mr. Haughton?”

“I don’t mind taking a hand.”

They sat down, Harris and Jackson against Starr and Haughton. They played for some time, but after the first game or two all the luck went over to Haughton and his partner. Harris, who was a volatile sort of fellow, after a great deal of restlessness, proposed changing the game to euchre. The game was changed, but not the luck; Haughton and Starr still won. It was about ten o’clock when they left off playing, the winnings then amounted to a couple of pounds or so. Haughton proposed to his partner that they should play off—who took the lot. They did so, and Haughton won. Starr rose, and, going into his room, brought out a couple of pair of blankets.

“You will have to be contented with a shake down to-night, Mr. Haughton; I have no spare bed to offer you.”

“Oh, I will do right enough,” said the other, smilingly. “I will sleep in the verandah; it is cooler.”

He went outside, after bidding the others good night. Jackson was sitting on the table, playing at patience with the cards.

“Well, I intend starting early to-morrow, so shall say good night,” said Starr.

“All right, but don’t go just yet; it is not so very late. I have any amount of news to tell you, but I cannot get it all out at once,” returned Harris.

“Well, let us hear some of it”

“You know Rowdy Jack, who was horse breaking for you?”

“Yes.”

“He has got bored and is lodging at the expense of the country for three years.”

“It is certainly news that he has got it, but none that he deserved it. Anybody else come to grief?”

“Yes, two or three married.”

“You call that coming to grief, do you?” said Jackson, putting the fourth story on a card house.

“In most cases I do,” said Harris. Jackson’s card house came down with a run.

“What do you know about it,” he said.

“I am a married man, and speak from experience.”

“You married, Harris! You are only joking.”

“No, unfortunately, I am not. You two fellows are old friends, so I will tell you all about it.

“When I came out here ten year ago a regular new chum, I went up to live at Bloomfield’s station, on the Wantagong. I had been up there about two years, and being only a raw, foolish boy found it very dull after the first novelty wore away. The place is all cut up into farms now; it was pretty well selected on even when I was there. I got very intimate with one of the selectors, an old fellow named Delaney, who used to live upon his wits I suppose, for it was very little I ever saw growing on his selection. I said that I got intimate with him. I ought to have said with his daughters. They were the attraction. The eldest I thought a regular beauty. Looking back on her now with the utmost detestation, I must admit she had remarkable good looks. She possessed a great deal of tact, too, and concealed her defects of manner and education admirably. I fell over head and ears in love with her; she was two or three years older than I was, and could do anything she liked with me. One day I called just as the priest, one Father Carroll, was leaving. I went in and found Mary crying, sobbing at least. Of course I was up in arms directly, and when we got by ourselves I insisted upon knowing the cause of it. After a great deal of feigned bashfulness and reluctance, she told me that Father Carroll, whom the Lord confound, had been warning her, telling her that my visits were becoming common talk, that I was only trifling with her, meant nothing serious, and all the many hints you can imagine. I am convinced now that this was nothing else but lies from beginning to end. Father Carroll, who was much respected in the neighborhood, knew too much of her to talk in that strain; repentance was the subject he would be most likely to choose for his homily. I confounded him just now, for if his name had not been introduced I do not think I should have been worked upon like I was. How I could have been such a mad infatuated fool is incredible to me now. But I was only a boy, and she and the devil had regularly ensnared me. I had a little money, not much; rumor had greatly magnified it, and they thought they had a prize. Anyhow, to make short work of it I married her that day week. I left the cottage immediately after the priest had married us, and hastened home to prepare a place to take my wife to. When within two miles of home I met a man on horseback. He pulled up at we came together, and I recognised a young fellow who had left the station shortly after I arrived on it.

“I was looking for you,” he said. “They told me I should find you down at old Delaney’s. I am looking for some horses of mine that are running down this way. Mr. Morgan (the superintendent) told me that you knew where they were running.”

I was in a hurry, but the horses were no distance away I knew, so I turned off to show him the place. He commenced asking me about the people in the neighborhood as we went along; he said that he had been in Queensland ever since he left the station, and only came back two or three days ago.

“You have been down seeing the Delaney, girls,” he went on to say; “how is Mrs. Morgan?”

“Mrs. Morgan,” I said. “I don’t know her.”

“Why Mary Delaney, of course. Did you not know that she consented to be Mrs. Morgan for six months or more? She might have become Mrs. Morgan in reality, for she was making a regular fool of him, but old Bloomfield in Sydney heard of it, and he saw that he had either to lose her or his billet, so he sent her away. That is not the first trial she has had of married life, and her sisters, I suppose, are running the same track. They say that you are down there pretty often.”

“He had scarcely finished speaking when we caught sight of his horses, and he started after them, leaving me to meditate on the pleasant piece of information he had just imparted to me.

“I did not do anything sudden or rash, but rode quietly home. Next morning I left the district, never to return. I wrote to her a letter I do not think she would forget very easily, and have made her an allowance—as much as I could afford—ever since, on condition that she never called herself by my name or attempted to join me. She consented perforce, for I went to New Zealand, and remained there for three years.”

“Have you heard of her lately; are you sure your information was correct?” said Starr, after a pause.

“I have; and her conduct since my departure fully comes up to, nay exceeds, the character I heard of her.”

There was a pause of some minutes, during which the regular breathing of the sleeper outside could be heard.

Jackson’s attention was attracted by it.

“Who is he?” he said, in an undertone to Harris, indicating the object of his remark by a move of the head.

“I don’t know; I only met him a day or two ago, and we travelled down together. He says that he has been in the army.”

“Looks more like a skittle-sharper,” said Starr, rudely.

“Don’t be spiteful now, because he won when you played off!”

“Not I, but I saw something that you fellows didn’t see. The stakes were not worth making a noise or a scene about, but the cards know him as well as he knows them.”

“What! Did he cheat?” said Harris, turning as red as fire.

“Something very like it.”

“Confound him forever. To think of my having brought him here. Old Fitzpatrick introduced him to me; he seems to have been educated, and I supposed that he was as good as most of the other men you meet. “

“Of course, Harris, it is impossible to know what a man is from just riding along a road with him. Good night,” he went on, shaking hands, “we shall have breakfast at sunrise to-morrow, but you need not get up unless you are going to start early too.”

“I am off the first thing,” replied Jackson. “And Harris, of course you will come to my place to-morrow?”

“Yes. But I have a good mind to wake Mr. Haughton up, and tell him something that will stop him from proceeding with us to-morrow. I feel almost as though I had been found out doing something dirty myself.”

“Oh, nonsense,” said Starr, “it is not worth speaking about; only don’t play at cards with him any more.”

By sunrise next morning breakfast had been despatched, and the horses were ready, saddled. Haughton complained of an attack of fever, and declined any breakfast. Starr and Jackson bade him good morning, and made some ordinary remarks.

Harris stalked by him like a muzzled tiger past a shin of beef.

Haughton took no notice of his changed behaviour, though it was open enough. He said that he would ride slowly and overtake them in an hour or two if he felt better.

The station was soon tenanted by the cook and stockman only. Haughton’s horses were in the yard, and about an hour after the others had left, the men saw Haughton catch and saddle them, then ride away along the same road taken by Jackson and Harris.

They had pushed on, and by three o’clock arrived at Jackson’s station, Glenmore. Harris was easily persuaded to stop the next day, the station of which he was superintent being only fifteen miles distant

“Mr. Haughton does not seem to be showing up,” he said, as he was preparing to start the following morning.

“No, he could not help noticing your behaviour towards him. I will be down your way in a day or two—good bye.”

Chapter II

On the second day after Harris’ arrival at home, Jackson rode up to the station, a black boy following him. Harris came out to meet him, and was immediately struck by the gray expression of his friend’s face.

“Why, Jackson, you look serious enough for half-a-dozen parsons; what is the matter?”

“Starr has been murdered,” returned Jackson, shortly.

“Good God! You can’t mean it”

But Jackson’s face assured him that he did mean it.

“He was found dead at Yorick’s Lagoon, shot through the head. Here is his black boy, Dick, who found the body.”

Harris turned to the boy.

“Mr. Starr been killed?”

“Yöi; ben shootem here,” touching the top of his head.

“Had he been robbed too, Jackson?”

“There were no tracks of any other horse but his own within two miles of the place; no signs of a struggle, and his body appeared to be untouched by anybody after falling.”

“And the gold?”

“No gold was found upon him. Some papers, two or three £1-notes, and some loose silver, were all the articles of value on his person. His horse was found with a mob of station horses, but without the valise, which Dick says was on the saddle when he left the Blatherskyte diggings. This is all I can learn from Dick. If you can come we will start back at once. An inquest will be held to-morrow or the day after; Williams has gone up to Blatherskyte.”

All that was elucidated at the inquest was, that on Monday, the 24th of January, James Starr had left Blatherskyte diggings alone, leaving a stockman named Williams and the black boy, Dick, to come on slowly. He was not again seen alive by anybody then present. Williams stated: That he was a stockman in the employ of the deceased; assisted him to drive a mob of fat cattle to Blatherskyte; that he left the diggings on the same morning, though some hours later, than the deceased did; a storekeeper of Blatherskyte, named Thompson, and the black boy, Dick, accompanied him; went as far as the creek called the “Twenty-mile,” and camped there that night; arrived at Yorick’s Lagoon about twelve o’clock; saw the body of a man lying at the edge of the water; the upper portion of his body was on a log; went over to it and found it to be the body of his employer, James Starr; a bullet wound was visible on the top of his head; appeared to have been dead about twelve hours; the body was quite stiff; deceased had some gold in a valise in the front of his saddle when he left the diggings; did not know the amount; found his horse close to the station, with some other station horses; the saddle was on the horse, but no valise.

Thompson’s testimony was to exactly the same effect.

Jawdon, a butcher of Blatherskyte, stated that he paid the deceased the sum of one hundred and sixty ounces of gold, and a cheque for £155, before he left the diggings; it was in payment for cattle sold and delivered to him by the deceased; saw the deceased put it into a valise and strap it on in front of his saddle; made some remark at the time about the horse getting away with it on; Starr left his place immediately afterwards; did not see him stop anywhere as long as he was in sight; believed that he went straight away. Williams, recalled, stated that after finding the body the black boy, who was an excellent tracker, went round with him to look for tracks; saw no fresh tracks of wither horse or man, excepting the track of deceased and his horse; knew the track of deceased’s horse by his having been newly shod on the diggings, and having a very peculiar shaped hoof; could swear to it; had shod the same horse himself at various times; the track of Starr’s horse went straight to the place where the body lay, and from then back to the road, and along it until the horse joined the mob he was found with; the lagoon was a small piece of water, about five miles from the station, close to the road; saw no horse tracks on the other side of the lagoon; it was about thirty to forty yards broad; cattle had been watering on the opposite side of the lagoon during the previous night; saw fresh tracks of a large number; saw the tracks of Starr’s horse all the way along the road to Yorick’s Lagoon; saw no other fresh tracks; met no one on the road.

The medical testimony showed the cause of death to have been a bullet wound in the top of the head; bullet produced was a small one seemingly, belonging to a very small bored rifle.

Jackson and Harris were examined, but of course their testimony threw no light on the affair. Suspicion first settled on Starr’s discharged cook. He was found at a public-house, some fifty miles from the scene of the murder. Had gone there direct from the station, and had been there ever since, “on the spree.” Several witnesses could swear to his presence there at all hours of the day and night.

Haughton was then enquired for, and found at Imberwalla. Proved to have stopped at a shepherd’s hut, six miles beyond Glenmore station, the night after he left Stratford; he accounted for not calling at the station by mentioning the changed manner of Harris towards him; arrived at Imberwalla three days after wards; had to camp on the road, on account of sickness; was still suffering from fever; did not possess either a rifle or revolver; had not had one for the last six months.

A verdict of willful murder against some person or persons unknown was returned; but years passed and nothing ever transpired.

Dick went into the service of Harris, and one day passing the scene of the tragedy he persuaded Harris to ride over, and then made an explanation which seemed to have been troubling him.

“You see, Mitter Starr bin get off to drink, lay down, like it there, doss up along a log. Some fellow been come up along a nother side, you see, where cattle track big fellow come up. That fellow bin shoot em Mitter Starr when he bin stoop down drink. Then go away along a cattle track. Cattle come up along at night, look out water, put em out track all together.”

Dick’s conclusion struck Harris as being correct, but it went no further towards pointing out the murderer.

Chapter III

More than twelve years after the events of the last chapter, Jackson and Harris met in Sydney. They had not seen each other for several years, both having left the district in which they formerly resided.

“Jackson, you must come and stay with me for a while. I want to introduce you to my wife. No! not the one I told you about. She is dead, died from drink I believe. I heard she was dying, and went to see her. If I had not seen it, I could not have believed that a woman could alter so. I am not a hypocrite, Jackson, nor are you, so I can say thank God she is dead without fear of your pretending to be shocked. No! I can show you a wife I am proud of.”

Jackson stayed several days with Harris, whose wife certainly merited her husband’s praise. One evening the conversation turned upon spirit rapping. Mrs. Harris remarked that some friends of hers, who were devout believers in it, had pressed her strongly to accompany them to a séance the next evening. She did not at first mean to go, but on Harris and Jackson saying that they would accompany her, they made up their minds to see the wonders of spirit-land the next evening.

Mrs. Harris’ friends called at about three o’clock in the afternoon, and the party, after proceeding down several rather shabby streets, stopped at a more than rather shabby house.

Jackson whispered that he wondered the spirits did not select a more fashionable, or at least a cleaner, neighborhood to make their communications in. After payment, they were shown into a dimly-lighted room, where several other well dressed persons were present. Some were seated round a table, others standing. The medium and another person, who was not a medium at present, only a disciple, were holding a conversation on spirit-rapping for the good of the company.

The medium was a thin-faced, crafty-looking man, evidently in bad health. Not bad looking, but still not exactly prepossessing. After a time, he seated himself at the table, the disciple left the room, and silence was demanded. The medium having explained the meaning of the knocks, what one knock stood for, etc, put himself into communication with the spirits. Several people asked questions of deceased relatives, some trustingly and confiding, others sneeringly. Sometimes the answers were strangely correct, to judge from the countenances of the enquirers; others, and by far the greater number, were as evidently wrong. Presently a conversation arose, which soon ended in a discussion between believers and unbelievers.

The medium then took a pencil and paper, and stated; “that any of the company might write a question on a piece of paper, fold it, and lay it on the table; that his arm would be guided by the spirits to write the answer, without having seen the question. This was evidently the display of the evening, and the company evinced a good deal of interest in the proceeding.

As before, some few of the answers seemed to be correct, and the majority wrong. The spirits, to judge from the manner in which the medium jerked his arm about, were fighting for possession of the pen.

Harris and Jackson determined to ask a question out of fun. Harris took out a note-book, wrote a question on a leaf, tore it out, and then handed the book to Jackson. He took it, but did not write anything. Harris walked up to the table and placed his folded paper on it; at the same time looking half-laughingly, half enquiringly, into the face of the medium, immediately afterwards though turning his gaze on to his wife.

The medium’s sharp black eyes looked for a moment disconcerted, as they met Harris’ frank look, but they noted its after direction, and a curious puzzled expression came into them. The spirits at first did not seem inclined to answer the question, but presently the mystic arm moved, and with a doubtful look, which soon changed into a triumphant one, the seer handed the answer to Harris.

It was a small piece of paper, and there were only two words on it, but they were quite enough to make Harris look at the medium with a scared face that was quite ludicrous; he drew back without speaking.

Jackson, who had been intently watching his friend’s success, wrote a question rapidly on a sheet of the note-book, tore it out, folded it, strode forward, and laid it on the table.

The medium looked at Jackson, his lips moved, but no sound came. His face grew very pale, and his gaze turned with a fixed look on the folded paper; it deepened into such an expression of intense and absolute horror as to startle the surrounding company. It was evident to the most sceptical that there was no acting now. His hand moved over the paper and formed a few hasty words, he folded it, trembling as he did so, handed it to Jackson, and fell with a deep groan on to the floor.

Jackson, nearly as startled and scared-looking as the prostrate medium, put the paper into his pocket, and stooped over the fallen man. The rest crowded round, the people of the house were called, and they conveyed the pallid conjurer, now slowly recovering from his swoon, out of the room. The séance was broken up, and the company began to disperse. Some expressed great curiosity to see the answer which had produced such a commotion. Jackson, however, did not satisfy them, they looked for his question, but that and the former one had disappeared. “Taken by the spirits,” one devout believer suggested. In reality quietly pocketed by Harris during the confusion occasioned by the medium’s collapse.

Harris, his wife, and Jackson, left their friends a short distance from the spirit’s residence and went home. Scarcely a word passed between them on the way. Jackson appeared to be lost in deep thought. The only remark he made was—

“Did you ever see that fellow before, Harris?”

“Never that I know of,” was the answer.

Jackson was silent the rest of the way.

When Jackson and Harris were alone in the room, Mrs. Harris having gone upstairs to remove her bonnet, etc., Harris drew forth the two questions, his own and Jackson’s. He handed his to Jackson. It was—

“If the spirit of my first wife is really present let her sign her name.”

“Here is the answer,” he said.

“Mary Delaney.”

Jackson looked very scared and excited as he almost whispered, “Look at my question, then we will look at the answer.”

Harris read—

“Who was the murderer of James Starr?”

Jackson opened the paper, the writing on which no one but the unhappy seer had as yet seen.

On it was written in a good, bold hand, differing entirely from the writing on Harris’ paper—

“Rudolph George Rawlings, known to you under the name of Haughton”

“It was him! I knew it!” exclaimed Jackson, in a voice which brought Mrs. Harris into the room in a fright.

“Who? Who?” cried Harris, nearly as excited as his friend.

“Haughton himself; I thought I knew him. No wonder he should faint; he wrote and handed to me his own death warrant.”

Harris still held the paper in his hand.

“Look Jackson,” he said, “it is Starr’s handwriting,”

He went to a bookcase and took down a book, on the fly-leaf was written, “T. C. Harris, from James Starr.” The handwriting was identical!

“Let us go at once and get a warrant, and have him arrested,” said Jackson, whose excitement could scarcely be controlled.

“We have no evidence to do so,” replied Harris; “we are no nearer towards doing justice on Starr’s murderer than we were before. This may carry conviction to you and me, but what magistrate would issue a warrant on such a lame story. We can inform the police that suspicious circumstances connect this medium—who you may be sure is well known to them—with the Haughton who was mixed up with Starr’s murder. They may find out some further evidence, but we are powerless. “

A knock at the door. Mrs. Harris, who was listening with a white face, went and opened it. The servant said that a woman wanted most particularly to see Mr. Jackson. Harris looked at him, then told the servant to show her up. She came in, a faded-looking woman, who handed a slip of paper to Jackson.

He read on it— “Come and see me before I die. R. Rawlings.” He passed it over to Harris; his wife read it over his shoulder.

“I will come with you,” said Jackson to the woman.

“And so will I,” said Harris.

She led them back to the house of the séance, to a room with a miserable bed in it, wherein lay the man they had seen acting the part of medium. He gazed wistfully at Jackson and spoke very feebly, and in abrupt sentences.

“I am dying, but I will tell you how it was done.”

The woman left the room, and closed the door.

“That night, which you remember as well as I, I went out on the verandah to sleep. I did not go to sleep until long after you all went to bed. I heard every word you said. I heard Harris tell the story of his marriage, which enabled me to make the lucky answer I did today. I knew you both directly you came in. I heard Starr expose me about the cards in a contemptuous sort of way that made me hate him. This led me on to recall your talk about the gold. I determined to rob him, but I was a coward, and assassinated him. I had not the courage even of a common bushranger to stick him up. I knew the exact day he would be back, as you know. I feigned sickness the next morning, and only went as far as the shepherd’s hut. The next day I went on a short distance past Harris’ place and camped. That night after dark I started back to Yorick’s Lagoon.

“I meant to conceal myself behind the bushes growing on the bank, and shoot him as he rode along the road, which, as you know, is close to the lagoon. I reached the neighborhood of the lagoon about daylight. My keeping off the road as much as possible led to my coming in along the cattle track, on the side of the lagoon opposite to the road. I had a short rifle in my pack, the barrel taken off the stock, which was the reason you did not notice it. I tied my horse up some distance off, and went down the dusty cattle track to the water’s edge on foot. There I waited the whole of the morning—how long it seemed! It was about three o’clock when I saw Starr coming. I was about aiming at him, when he pulled up, got off and stooped down to drink. He was right opposite to me, his horse drinking alongside of him, his head down on the surface of the water. I was a dead shot, and struck him right on the top of the head. He scarcely seemed to move; his horse gave a slight start and snort, stretched his neck, and snuffed once or twice at the body of its rider; presently, finding itself free, began feeding, and after a few minutes’ nibbling at the grass, walked towards home.

“I was in doubt what to do, but determined to follow the horse and obtain the valise. Should the gold not be in it, I would have to return and search the body. During the latter part of my watch, several mobs of cattle had come along the track I was lying on, smelling me when they got close; they had run back again. This gave me the idea of following the track back for a couple of miles, trusting to the cattle to obliterate all marks of my presence. Starr’s horse seemed to be making straight home. I determined to chance finding him somewhere along the road. I followed the track out, took a circle round, and came on to the road just as Starr’s horse and some more he had picked up with came along. He was quiet and easily caught. The gold was in the valise. The presence of the other horses prevented my track being noticed, and by midnight I was back at my camp. At daylight I looked along the road, and saw by the tracks that no one had passed during my absence.

“I was safe. You know all about the inquest. I am ill of a terrible disease which plagues me with fearful torments. I must die in a day or two, perhaps to-night. Remorse now is useless, but I tell you that I have known little peace since I shot Starr. Leave me now, and don’t attempt to preach to me.”

Neither of the two friends felt either fitted or able to attempt it, and seeing that their presence there availed nothing, they left. But when they reached the foot of the stairs, Harris called the woman, and, giving her money, told her to call and inform him of the fate of Rawlings.

She came next morning and told them that he died a few hours after they left, never having spoken again.