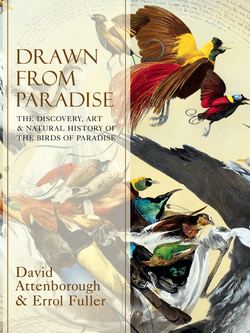

Читать книгу Drawn From Paradise: The Discovery, Art and Natural History of the Birds of Paradise - David Attenborough, Errol Fuller, Sir David Attenborough - Страница 8

Оглавление

Greater Bird of Paradise (detail). Jacques Barraband, c.1802. Watercolour.

The First of the Family – the Plume Birds

Genus Paradisaea

The first specimens of birds of paradise to arrive in Europe looked very odd indeed. Several were unloaded from a small weather-beaten ship, The Victoria, that docked on 6 September 1522, in the little port of Sanlucar de Barrameda, 32 km (20 miles) north of Cadiz on the southwestern Atlantic coast of Spain, and close to Seville. That the shrivelled dried skins had once been birds was evident from the fact that they had beaks. But there was no skull in the skin of the head, the flattened feathered bodies were entirely empty, and there was no sign of wings or feet. Two strange wire-like quills projected from the tail, each about twice the length of the bird’s body. But the most wonderful part of their anatomy was their plumes. Thick golden bunches sprouted from either side of the body. These plume feathers did not have barbs that link together into an air-catching vane like normal wing feathers. Instead, the barbs were thread-thin but rigid and widely separated, giving each feather a breath-taking gauzy delicacy. And the feathers were so long that lower down the body the two bunches amalgamated and extended far beyond the tail, had there been one, in a single glorious, golden cascade.

The Victoria was the only survivor of a small fleet of five ships that three years earlier had set out from Sanlucar, under the command of Ferdinand Magellan (1480–1521), in an attempt to reach the far distant Spice Islands, the small archipelago west of New Guinea that today is known as the Moluccas. Magellan planned to do so by sailing, not down the coast of Africa and then eastwards across the Indian Ocean as Portuguese rivals had done, but by heading west across the Atlantic, rounding the southern tip of South America for the very first time, and then crossing the vast emptiness of the Pacific. The expedition succeeded in doing so, but at great cost. It became embroiled in a local war in the Philippines and Magellan was killed. Four of the ships were lost – wrecked, burnt or so weather-beaten that they were abandoned. But The Victoria had survived and so became the first ship ever to circumnavigate the globe.

A Lesser Bird of Paradise painted from a wingless and footless specimen in the collection of Emperor Rudolf II. Joris or Jacob Hoefnagel, c.1600. Gouache on parchment, 36 cm × 27 cm (14 in × 11 in). National Library of Austria, Vienna.

Three early paintings of preserved skins of Greater Birds of Paradise.

Anonymous, c.1630. Watercolour and body colour, 23 cm × 9 cm (9½ in × 3½ in). Private collection.

Anonymous, sometimes attributed to Conrad Aichler, 1567. Watercolour and body colour, 45 cm × 22 cm (18 in × 8½ in). The significance of the inscription ‘Meralda’ is unknown, and the image bears some connection to the woodcut from Gesner’s Vogelbuch of 1557; the same preserved skin may have served as the model. The distorted shape of the head is due to Papuan methods of preservation – the skull was removed during the drying process. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden.

Anonymous, c.1560. Watercolour and body colour, 59 cm × 37 cm (24 in × 15 in). Graphische Sammlung, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg.

Her crew had wonderful tales to tell – of new lands and new peoples, of Patagonian giants who quenched hunger by thrusting arrows down their throats so that they threw up their meals and could eat them again, of sea monsters that threatened their ship, and of gigantic birds so big they could pick up elephants in their talons. The shrivelled skins were proof of another marvel – birds that floated high in the skies beyond the sight of men. There they fed on dew, and were only found by humans when they died and fell to earth. That was why, as all could see, the skins lacked both wings and feet. The people in the Spice Islands called these wonderful creatures ‘bolong diwata’, birds of the gods.

The skins had been presented to the expedition as a gift to the King of Spain by the Rajah of Bacan, one of the Spice Islands. But in truth neither the Rajah nor his people had any first-hand knowledge of the living birds. The specimens were brought to them by traders from lands far away to the east of their islands.

Most European artists and scholars seem to have accepted the stories about the birds’ way of life at face value, although the first known European drawing of these extraordinary creatures is an unflattering but honest portrayal conveying little of the wonder that was so captivating. Produced in 1522, very soon after The Victoria landed, by a German artist, Hans Baldung Grien (1484/5–1545), the plumes are indicated by just a few simple parallel lines. The skins were certainly circulating quickly. By October 1522 the scribe of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, was writing to a bishop in Salzburg explaining that he had acquired for the emperor (from The Victoria’s captain) the boneless body of a wonderful bird, ‘so that he may delight in its rarity and splendour’.

A second picture, made some 20 years later, and this time in colour, gives more than a hint of the magical legends that still surrounded the birds. It was painted by a Croatian artist, Giulio Clovio (1498–1578) and appears in a small illuminated prayer book, now known as The Farnese Hours. Clovio clearly accepted the stories of the birds’ connections with paradise, for he shows one sailing through the sky, trailing its plumes gloriously behind it, but without any sign of wings.

Even scholars and natural historians, whom one might have expected to be somewhat more critical, seem to have accepted the stories as truth. Ulysses Aldrovandus (1522–1605), in his great thirteen-volume encyclopaedia of natural history, which he started to publish in 1599, included illustrations of the bird drinking dew among the clouds. Other authors, pondering on how such creatures could perpetuate themselves – as they must surely do since they are mortal and die – stated as a fact that the female laid her eggs on the male’s back and then incubated them by sitting on both them and him as they sailed together through the sky. The wire-like quills projecting from the tail were also given a function. They, according to some accounts, were used as hooks with which the birds suspended themselves from the branches of trees when they wanted to rest from floating.

The first known European image of a bird of paradise. Silverpoint drawing by Hans Baldung Grien, 1522, 10 cm × 15 cm (4 in × 6 in). Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen.

The first known coloured image – painted on a page of the prayer book known as The Farnese Hours by Giulio Clovio, c.1540. Pierpont Morgan Library, New York.

Detail of Clovio’s picture.

Two fanciful birds of paradise drinking dew from the clouds, both apparently wingless and footless. Woodcuts from Ulysses Aldrovandus’ Ornithologiae (1599).

The Garden of Eden. Jan Brueghel the Elder, c.1617. Oils on oak panel, 53 cm × 84 cm (21 in × 33 in). Victoria and Albert Museum, London. A plumed bird of paradise is perched on the thinnest branch in the top left corner, and another flies just beneath.

The Earthly Paradise and the Fall of Man. A collaboration between Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder, c.1617. Oils on panel, 78 cm × 112 cm (29 in × 45 in). Mauritshuis, The Hague.

It was not until the seventeenth century that more rational ideas prevailed. The Garden of Eden was a popular subject for artists as it allowed them to paint pictures that had religious connections and yet also permitted the inclusion of images from the natural world. Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625) produced one in which a bird of paradise perches on a branch – on two legs. Close by is a toucan and a macaw, and beneath them another bird of paradise in flight – with wings.

Brueghel also produced a picture, The Earthly Paradise, in collaboration with his Flemish countryman Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640). Rubens is said to have painted the human figures, the horse, and the serpent in its tree, while Brueghel produced the rest. And on the ground stands a bird of paradise complete with wings and legs. Another flies to the left of the ostrich’s head. At last birds of paradise were being portrayed un-mutilated, as real birds. Nonetheless, even after Brueghel, legions of other artists continued to show birds of paradise magically floating across the sky with their plumes streaming behind them – unconcealed by wings.

Concert of the Birds. Frans Snyders, 1629–30. Oils on canvas, 98 cm × 137 cm (38 in × 54 in). Many pictures with this title were produced by northern artists during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. They nearly all show an owl in the centre holding up a sheet of music surrounded by other birds, open-beaked, singing in chorus. Doubtless, they were inspired by the common sight in the countryside of an owl that dared to perch out in the open during daylight being mobbed by other smaller birds. Those shown here are all European with the exception of a South American parrot on the right and a Greater Bird of Paradise, with somewhat faded and dusty plumes, on the left. The score held by the owl seems to make no musical sense but that, perhaps, is of little consequence, since nearly all the birds shown have extremely discordant voices. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

The boy who would grow up to be Charles I, King of England, with a sword hilt in his left hand and a hat decorated with the skin of a bird of paradise behind him. Robert Peake, c.1610. Oils on canvas, 127cm × 85 cm (66 in × 34 in). Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh.

As the decades passed, more and more of these extraordinary skins began to appear. They all came from the great 1,600 km (1,000 mile)-long island of New Guinea, lying north of Australia, or from its outlying archipelagos. From there they were traded right along the Indonesian island chain and into the mainland of Southeast Asia. Some went even further into the Himalayas to become part of the regalia of the Kings of Nepal, which they still are. They even reached Britain. A certain amount of evidence suggests that bird of paradise plumes were found among the personal possessions of Henry VIII after his death. The evidence that the ill-fated young Scottish prince who would become Charles I of England also possessed them is beyond question. About the year 1610 he posed for his portrait standing beside a table upon which he has placed a sumptuous fur hat with, pinned to it by a brooch, the preserved skin of a bird of paradise complete with plumes.

Just under 30 years later, Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–69) felt compelled to draw two specimens that, presumably, he had just acquired from a Dutch trading vessel, recently arrived from the East Indies. Rembrandt is known to have delighted in the rare and the curious, and such tastes were among the weaknesses that eventually led him into bankruptcy. When his goods were finally impounded and inventoried by bailiffs, a bird of paradise skin was listed among them.

The birds brought back by Magellan’s men had in life – as well as gauzy plumes – yellow heads, bibs of rippling iridescent green, and brown bodies. Grien’s drawing doesn’t show quite enough detail positively to establish that they were Greater Birds of Paradise, although there are good grounds for supposing that they were. But there are, in fact, half a dozen species that fit the description. Carl Linnaeus (1707–78), the great Swedish cataloguer of the natural world, invented a generic name for them, Paradisaea. To the biggest of them, he added, no doubt with his tongue in his cheek, the specific name – apoda, meaning ‘without feet’. A second species, the Lesser Bird (Paradisaea minor), also has golden plumes but is slightly smaller and lacks a small brown feathery cushion that the Greater Bird wears on his chest. The yellow plumes have a tendency to fade dramatically in preserved specimens, which is why many artists, using such specimens as reference, have shown them as white.

Two birds of paradise. Rembrandt van Rijn, c.1640. Pen and bistre with wash and white body colour, 18 cm × 15 cm (7 in × 6 in). The Louvre, Paris.

Three other species, the Red Bird (P. rubra), Count Raggi’s Bird (P. raggiana) and Goldie’s Bird (P. decora), are somewhat similar but have plumes that are not yellow but red. A sixth, the Emperor of Germany’s Bird (P. guilielmi), which is restricted to a small patch of mountains near the eastern tip of the island, has genuinely white plumes that are even more lace-like than those of its relatives. It is only the males of each species that develop these ravishing plumes. The females are comparatively drab – brown above, somewhat paler beneath and often quite difficult to tell apart.

Count Raggi’s Bird of Paradise – the first known illustration. Hand-coloured lithograph by Joseph Wolf and Joseph Smit from D. G. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

The Emperor of Germany’s Bird of Paradise, male and female. Watercolour by William Cooper, c.1976, 60 cm × 47 cm (24 in × 17 in).

Greater Bird of Paradise, male. Engraving after a watercolour by Jacques Barraband from François Levaillant’s Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux de Paradis (1801–06).

Goldie’s Bird of Paradise, male and immature male. Hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart and John Gould from Gould’s Birds of New Guinea (1875–88).

The Red Bird of Paradise. Engraved plate, printed in colours and finished by hand by Jean Baptiste Audebert, from Audebert and Vieillot’s Oiseaux Dorés ou a reflets Metalliques (1802).

Lesser Bird of Paradise, male and female. Watercolour by William Cooper, c.1976, 60 cm × 47 cm (24 in × 17 in).

Something of the wonder and curiosity that was inspired in naturalists by the arrival of bird specimens in Europe is captured in a painting by Ramsey Richard Reinagle (1775–1862). Painted around 1800, it shows a taxidermist examining the skin of a plumed bird of paradise newly arrived from foreign parts, with an Argus Pheasant lying on the table beside him. Some controversy exists over the identity of the man in the painting. An old inscription on the reverse identifies him as ‘Mr Thomson, animal and bird preserver to the Leverian and British Museums’, but during recent decades the picture has been listed as a portrait of the celebrated English ornithologist John Latham (1740–1837). That this identification is incorrect is shown by the presence of a Lyrebird specimen hanging on the rear wall. Lyrebirds did not arrive in England from Australia until around 1800, by which time Latham would have been 60 years old. The most likely interpretation of the painting is that it shows the otherwise unknown Mr Thomson inspecting the recent arrival and considering its suitability for proper stuffing.

The Greater and the Lesser Birds were both portrayed in one of the first of the spectacular folio books that deal with the birds of paradise. It was written by the French zoologist Francois Levaillant (1753–1824) and published in 1806. Its great distinction lies in its plates, which were drawn by one of the finest of all bird artists, Jacques Barraband (1767–1809), who had the most extraordinary ability to represent the many different textures that feathers may have. Until the last decades of the twentieth century, his ornithological reputation rested largely on these engraved hand-coloured plates. But they give little hint of Barraband’s true talent. The exquisite watercolours on which the engravings were based were almost entirely unknown. They had been acquired privately soon after they were painted and had remained in private possession, carefully preserved in albums that have protected them from fading ever since. It was only during the 1980s that the collection was split up and the full beauty and accuracy of the artist’s work was revealed to the world.

But Barraband, like all his predecessors and those that followed him in the next few decades, had to work from skins. Consequently, their interpretations were, at best, inaccurate and often downright wrong. But then no European explorer travelling through New Guinea had even seen the living birds in the wild. The first to do that was a French traveller, René Primevère Lesson (1794–1849). He was serving on board a corvette, La Coquille, as the ship’s naturalist with the explicit task of collecting zoological specimens. Going ashore in July 1824 at Dorey Harbour, today’s Manokwari, at the western end of New Guinea, he glimpsed one of the birds. ‘Whilst we were walking very carefully on a wild pig trail through the dense scrub,’ he wrote, ‘suddenly in a slight curve a bird of paradise flew gracefully over our heads; trailing light like a meteor. We were so amazed,’ he added, ‘that the flintlocks in our hands did not move.’

Mr Thomson, Animal and Bird Preserver to the Leverian and British Museums. Ramsey Richard Reinagle, c.1800. Oils on canvas, 147 cm × 147 cm (58 in × 58 in). Courtesy of The Yale Centre for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, New Haven.

Two watercolours by Jacques Barraband, c.1800.

An immature male Lesser Bird of Paradise. 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in).

Greater Bird of Paradise. 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). This painting was used as the basis for an engraved plate, printed in colours and finished by hand in Levaillant’s Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux de Paradis et des Rolliers (1801–06).

Red Bird of Paradise, male, one of the species that Alfred Russel Wallace encountred during his travels in New Guinea and its surrounding islands. This engraving by T. W. Wood was one of a number of pictures produced for the celebrated book that Wallace published on his return to Britain, The Malay Archipelago (1869). A curiosity of this particular species is the structure of the two long central tail feathers. In other birds of the genus these resemble thin wires, but when examined closely those of the Red Bird are more like straps of plastic.

Eventually, however, he did shoot specimens which were brought back to Europe and duly described in his book, the first treatise to be devoted to birds of paradise by someone who had actually seen living specimens. It is illustrated by several rather undistinguished (although charming) plates, drawn by French artists Paul Oudart (1796–c.1860) and Jean-Gabriel Prêtre (fl. 1800–50).

But even Lesson did not see the birds in display. The first European to do that was an Englishman, Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913). He was a self-educated man of limited means, but with a passion for natural history and a burning ambition to see nature at its most varied and wonderful in the tropics. He planned to pay for his journey there by collecting natural history specimens and selling them to museums and wealthy collectors. His first journey to the Amazon had ended in disaster when, after four years of arduous travel and industrious collecting, he started on the return journey to Britain. Three weeks out to sea, his ship caught fire and he lost thousands of carefully prepared specimens and all his meticulous field notes. He was lucky to escape with his life. When he at last reached Britain, nothing daunted, he made preparations for another expedition. This time, he decided to go to New Guinea, expressly to search for birds of paradise.

Landing in Singapore, he started a series of journeys travelling from island to island in local craft, and living often in conditions of great hardship. Eventually, he reached the Aru Islands that lie south of the western tip of New Guinea and established himself in the trading village of Dobbo. Here men came from all over south-east Asia to obtain bird of paradise skins that were still being prepared in the same way as in Magellan’s time. And eventually, by following the hunters into the forest, Wallace found a tree in which Greater Birds were displaying. This is how he described the scene:

The birds now commenced what people here call their ‘sicaleli’ or dancing parties, in certain trees in the forest… which have an immense head of spreading branches and large but scattered leaves, giving a clear space for the birds to play and exhibit their plumes. On one of these trees a dozen or twenty full-plumaged male birds assemble together, raise up their wings, stretch out their necks, and elevate their exquisite plumes, keeping them in a continual vibration. Between whiles they fly across from branch to branch in great excitement, so that the whole tree is filled with waving plumes in every variety of attitude and motion. At the time of [the bird’s] excitement, the wings are raised vertically over the back, the head is bent down and stretched out, and the long plumes are raised up and expanded till they form two magnificent golden fans, striped with deep red at the base and fading off into the pale brown tint of the finely divided and softly waving points. The whole bird is then overshadowed by them, the crouching body, yellow head and emerald green throat forming but the foundation and setting to the golden glory which waves above. When seen in this attitude, the Bird of Paradise really deserves its name, and must be ranked as one of the most beautiful and wonderful of living things.

This, published in 1869, is the first account of the display of any bird of paradise and it could have been a good guide for anyone who tried to portray the dance of any species in the genus Paradisaea. Four years after it appeared, a wealthy American ornithologist, Daniel Giraud Elliot (1835–1915), published a huge book on the family, measuring 61 cm by 48 cm (24 in by 19 in), with plates drawn by Joseph Wolf (1820–99), a German artist who had settled in London. Wolf was already recognised as one of the great zoological artists of his time, whose pictures not only brought splendour to scientific publications but, on occasion, were hung in London’s Royal Academy of Arts. He must surely have known of Wallace’s description, for the book he illustrated for Elliot is dedicated to Wallace. Even so, the individual that dominates his plate of the Greater Bird is shown with relaxed plumes. Only in the distance and on a much smaller scale does he portray the display posture, and then he does so rather hesitantly – and inaccurately.

Greater Birds of Paradise, two males and a female. Hand-coloured lithograph by Joseph Wolf and Joseph Smit from D. G. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

He was bolder with his picture of the Lesser Bird. This plate is certainly one of the glories of Elliot’s book, and it shows the bird with plumes erect in a spectacular haze that extends to the very margins of the huge plate. Glorious though it is, it too in its details fails to match Wallace’s description.

Strangely, when in 1869 Wallace himself published his much delayed account of his travels, the artist T.W. Wood, who was given the task of providing the illustrations, also failed to show the birds’ display posture correctly, and makes it appear that the plumes sprout from above rather than beneath the wings. It seems very odd that such an accurate and meticulous observer as Wallace did not correct him.

In the year 1874, the challenge was taken up by the most famous ornithological publisher of his time, John Gould. (1804 – 1881). Gould had started his scientific career with the Zoological Society of London, where as taxidermist he had the responsibility of preserving the mortal remains of the rare animals that died in the Society’s Gardens, the London Zoo. In 1830, he had published a set of illustrations based on a collection of bird skins that had been sent to the Society by a collector working in the Himalayas. It proved to be a great success and it set the pattern for the publications which occupied him for the rest of his life.

Each work Gould produced was issued in parts, each part containing a dozen or so plates accompanied by a scientific text written by Gould himself. The plates were spectacular, approximately 55 cm tall and 37 cm wide (22 inches × 14 inches), and each species had a plate to itself. Gould himself had little talent as an artist but in most cases he would make a rough sketch showing the composition he had in mind which he gave to an artist. Initially this was his wife, but after her untimely death he engaged a succession of specialist ornithological illustrators. Each had the difficult and highly specialised task of deducing from a dried feathered skin what the bird must have looked like in life. The drawing was then transferred to lithographic stone, either by the original artist or by a draughtsman specialising in such work, and from this an edition of several hundred black and white copies were printed. Each print was then coloured individually by hand to match the original drawing.

The parts, each with its dozen or so plates, were then sent to subscribers over a period that sometimes extended for several years before the entire work was complete. Often, Gould would add new parts to the number listed in his prospectus, as new species were discovered Sometimes, he would start on a completely new project before its predecessor was finished. His Himalayan Birds were followed by The Birds of Europe. Then came a survey of the toucan family and another of trogons. After that he tackled The Birds of Australia and started on yet another long-running series devoted to hummingbirds. And in 1875 he began work on The Birds of New Guinea and engaged as one of the primary artists, an Irishmen, William Hart, (1830–1908) who had already worked on several of his previous volumes.

Lesser Birds of Paradise, male and female. Hand coloured lithograph by Joseph Wolf and Joseph Smit from D. G. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

Lesser Birds of Paradise, males. William Hart, c.1875. Oils on canvas, 34 cm × 24 cm (13½ in × 9½ in). Private collection.

Goldie’s Bird of Paradise, male and immature male. William Hart, c.1875. Oils on canvas, 34 cm × 24 cm (13½ in × 9½ in). Private collection.

At least two of Hart’s oil studies survive. One of these shows Goldie’s Bird, which has red plumes and the artist, perhaps becoming confused by the illustration in Wallace’s own book, shows them, incorrectly, as being erected beneath the wings rather than being raised above them.

The subject of the other study, a Lesser Bird, is apparently in display but also shows the plumes incorrectly raised and they droop rather limply instead of trembling as Wallace so vividly describes.

Maybe Wallace commented on these attempts, for by now he was well settled in Britain and in touch with London’s circle of naturalists and scientists. Whether he did or not, the plate of the Lesser Bird that Hart eventually produced for Gould is a great improvement. It shows the bird in almost a correct display posture – tail depressed, wings erect, with its plumes raised above its back, and squawking vigorously.

But it was left to William Cooper, in 1977, illustrating a monograph written by Joseph Forshaw, to finally produce a truly accurate picture of one of these Paradisea species at the height of its ecstasy. The species in question is the red-plumed Count Raggi’s Bird, and Cooper’s painting, used on the dust wrapper of his book, shows – in exquisite detail – a male, head lowered beneath the branch on which it perches, displaying his magnificent plumes in a great scarlet fountain above his back, while a female watches critically.

Still life with Sword, Velvet and Lesser Bird of Paradise. Dirk de Bray, 1672. Oils on canvas, 37 cm × 52 cm (15 in × 21 in). Private collection.

But one species in the genus stands apart from the other six. It does not have a golden head or an iridescent bib like all the others in the genus. Instead its head and body are a comparatively sober black. But its wing feathers and its plumes are blue, pale on its wings and intense in its plumes. And yet on their reverse side these same plumes are coloured rust red. Indeed, the species is so different that some authorities believe it should be given a genus of its own. It was discovered in 1884 by the German explorer Carl Hunstein in the then little-explored mountain range that runs down the centre of eastern New Guinea. Hunstein sent this specimen to another ornithologist, Otto Finsch, who duly named it Paradisaea rudolphi after Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria. In Finsch’s ingratiating dedication he described the Prince as ‘the high and mighty protector of ornithological researchers over the entire world’. Sadly the prince was to become rather more famous a few years later for dying in a suicide pact with his lover at a hunting lodge at Mayerling.

Lesser Bird of Paradise, with plumes of exaggerated length. Wilhelm Kuhnert. Oils on canvas, c.1900. Size and whereabouts unknown.

Count Raggi’s Bird of Paradise, male and female. William T. Cooper. Watercolour, produced for the dust wrapper of Cooper and Forshaw’s book The Birds of Paradise and Bower Birds (1977), 60 cm × 42 cm (24 in × 17 in).

By the time of this species’ discovery, John Gould was dead and his book on New Guinea birds had been completed by his friend Richard Bowdler Sharpe (1847–1909), who was in charge of ornithology at London’s Natural History Museum. But so many new species of birds of paradise had now been identified that Sharpe took on another task – to publish a work devoted exclusively to the family (together with the bowerbirds that were then thought to be closely related). Many of the plates were taken from Gould’s earlier work. Some were redrawn, and new plates of the latest discoveries were added, drawn once again by William Hart. Among these was the Blue Bird.

It is one of Hart’s more awkward compositions. The male stands on a branch above the female, feathers fanned out to either side, breast shield extended with a slightly wider, darker fan beneath and a pair of long, ribbon-like wires tipped with small blue discs, extending downwards. Clearly Hart was attempting to show the male in display, but he could hardly have posed the bird in a more inaccurate way. He can scarcely be blamed because the male Blue Bird, when he attempts to attract a female, puts on one of the most improbable performances of the entire family.

Unlike all the rest of the Paradisaea genus, the male does not display alongside others. Instead, each has his own display perch in the forest, a gently sloping branch usually within a metre or so of the ground. The owner arrives in the early morning, often alighting high in the canopy above, and calls to announce his forthcoming performance. Then he descends to his perch. Holding tight with his toes, he slowly swings backwards until he is hanging upside down and facing in the opposite direction. Now he expands his plumes so that they form a shimmering triangular fan that covers almost his entire body with its point beneath his neck. The two wires in his tail, now pointing upwards, fall in an arc on either side.

Male Prince Rudolph’s Blue Bird showing the surprising rust colour on the reverse of the blue plumes. Errol Fuller, 1994. Oils on panel, 40 cm × 25 cm (16 in × 10 in).

Male and female Blue Birds. Hand-coloured lithograph by William Hart from R. Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1891–98).

He begins to call, narrowing his white-lidded eyes until they are almost shut. As he does so he expands a patch of black feathers, rimmed with a rusty red on the edge near his feet. This now begins to pulse. With each expansion, a horizontal wave of shimmering ultramarine ripples upwards across the fan. And then he sings – if the sound he makes can be called a song. It is best described, perhaps, as an electronic buzzing interspersed with the shaking shuffle of maracas and a few random croaks, and it is unlike any other sound that comes from a bird’s throat.

The Australian artist William Cooper is one of the few painters who has attempted to portray this almost unbelievable dance, and he does so superbly. One suspects, however, that had William Hart or any other nineteenth-century artist tried to paint a picture of this surreal performance, his viewers would have regarded it as just as fanciful and improbable as they regarded Aldrovandus’ version showing the birds wingless and legless and floating in paradise.

Male Prince Rudolph’s Blue Bird of Paradise displaying to a female. William Cooper, c.1990. Acrylic on panel, 76 cm × 114 cm (30 in × 45 in). Private collection.