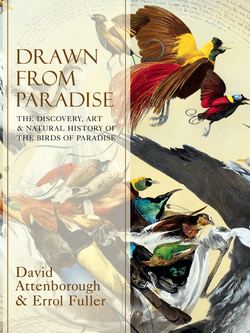

Читать книгу Drawn From Paradise: The Discovery, Art and Natural History of the Birds of Paradise - David Attenborough, Errol Fuller, Sir David Attenborough - Страница 9

Оглавление

Twelve-wired Birds of Paradise (details). Joseph Wolf. Hand-coloured lithograph from D. G. Elliot’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1873).

Two adult male Twelve-wired Birds of Paradise. William Hart and John Gould. Hand-coloured lithograph from Gould’s Birds of New Guinea (1875–88).

The Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise

Genus Seleucidis

The second distinct kind of bird of paradise to arrive in Europe, of which we have any record, is a very odd one, the Twelve-wired. Indeed, it is so odd that many might be surprised to know that it even belongs to the bird of paradise family at all. But to hunters collecting plumes in the forest of New Guinea, plumes are plumes. And plumes it has.

They sprout from the male’s flanks and are the same golden colour as the hunters’ usual quarry, the Greater and Lesser species. And they are unquestionably plumes, for the barbs on either side of each quill do not zip together like flight feathers and are nothing more than gauzy filaments. But they are not erectile and each bunch contains six that are twice the length of the rest. In their lower sections, which are buried within the rest of the plumes, these strange feathers are white and fringed on either side with very short barbs. But where they extend beyond the main bunch they are no more than thin naked quills which are a shiny jet black. These are the wires that give the species its name.

Doubtless the golden plumes were enough to attract hunters in New Guinea and persuade oriental traders to accept the skins, perhaps at a lower price, as second-best birds of paradise. At any rate, at the end of the sixteenth century, one example found its way across Asia and Europe and into that cabinet of curiosities assembled by the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (1552–1612) and kept at his castle in Prague.

Around the year 1600, he commissioned artists to produce a series of paintings of animals and birds living in his menagerie, and also of interesting specimens from his curiosity collection. Acting on the royal instruction, Dutch artist Joris Hoefnagel (1542–1601), or perhaps his son Jacob (1575–c.1630), painted a picture of the Twelve-wired.

The specimen must have arrived in Europe only recently, for the artist shows the colour of its flank plumes as bright yellow and – as we now know – they always fade to white after a few years. Indeed, they do so even in live captive specimens if they are not given pandanus nuts in their food. The emperor’s specimen, nonetheless, was clearly badly mangled. Its neck seems to have lost some of its feathers, for it is very scrawny, and instead of twelve wires, the bird has only ten, five on each side. That at least is understandable, for the wires, the quills, can become very brittle with age. Its other disfigurements, however, may have been inflicted by the native hunters who collected the specimen in New Guinea and treated it in the same way as other more famous species, the Greater and the Lesser, cutting off its wings and feet in order to emphasise the splendour of its similarly coloured golden flank plumes, and removing the skull to make preservation of the skin and feathers easier. Certainly there are no signs of either wings or feet in the painting, and the bird’s body and tail appear to be little more than a black tube with a clump of golden plumes flaring on either side like the engines of a jet aircraft.

It is easy to sympathise with the predicament Hoefnagel faced when he came to paint his picture. After all, he was confronted with a dried relic bearing only a passing resemblance to the creature in life, and he had, of course, never had the opportunity of seeing a living individual. Furthermore, birds of paradise – with their often peculiar arrangement of plumes, fans and wires – hardly conform to the morphological patterns shown in more familiar birds.

Perhaps because the illustrations Rudolf commissioned remained the private property of the Habsburgs, the painting was long overlooked by naturalists, and the Twelve-wired remained largely unknown in Europe. Even the great Carl Linnaeus failed to give it a scientific name in the 1758 edition of his Systema Naturae.

A Twelve-wired Bird with a Scarlet Ibis below. Joris or Jacob Hoefnagel, c.1600. Gouache on parchment, 36 cm × 27 cm (14 in × 11 in). National Library of Austria, Vienna.

Twelve-wired Bird of Paradise, painted soon after François Daudin scientifically described the species, and showing the faded plumes on which he based his description. Jean-Gabriel Prêtre, c.1810. Watercolour on paper, 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). Private collection.

It wasn’t until the year 1800, some two hundred years after Hoefnagel painted it, that the Twelve-wired was named scientifically and registered as an accredited member of the Bird of Paradise family. Then a French naturalist, François Daudin (1774–1804), a man who took up zoology despite the fact that his legs had been paralysed by a childhood disease, published a description of it. He recognised that although it was indeed a bird of paradise it was sufficiently different from any other species to be given a genus of its own. Searching, perhaps, for a name that might reflect its paradisal connections, he called it Seleucidis