Читать книгу Grove - Esther Kinsky - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеVillage

IN THE MORNINGS I would walk to the village via a different lane every day. Whenever I thought I knew every route, a staircase would reveal itself somewhere, or a steep corridor, an archway framing a vista. The winter was cold and wet; along the narrow corridors and stairs, moisture crackled in the old stone. Many houses stood vacant and around lunchtime the village was very quiet, almost lifeless. Not even the wind found its way into these lanes, only the sun, which usually stayed away in winter. I saw elderly villagers with scanty purchases, bracing their feet against the steepness. The people here must have healthy hearts, trained on these slopes, day after day, with and without burdens and beneath the weight of winter’s dampness. Some climbed very slowly and steadily, while others paused, drew breath—whatever breath there was to draw here, in the absence of light or any scent of life. On these winter afternoons, not once did I smell food. On brighter Sundays in the early afternoon, clattering plates and muted voices would sound from the open windows on Piazza San Rocco, but on gloomy winter weekdays the windows remained closed. There were no cats roaming about. Dogs which might have remained silent had they had a bone yapped at the occasional passersby.

Then one day the sun shone again. The elderly came out of their houses, sat down in the sun on Piazzale Aldo Moro and squinted in the brightness. They were still alive. They thawed like lizards. Small, tired reptiles in quilted coats trimmed with artificial fur. The shoes of the men were worn down on one side. Lipstick crumbled from the corners of the women’s mouths. After an hour in the sun they laughed and talked, their gesticulations accompanied by the rustle of polyester sleeves. During my childhood, they were young. Perhaps they were young in Rome, rogues in yellow shoes with mopeds, and young women who wanted to look like Monica Vitti, who wore large sunglasses and stood in factories by day, occasionally partaking in demonstrations, arm-in-arm.

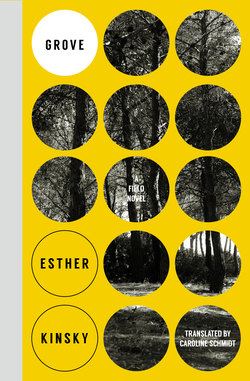

Above the valley whitish plumes of smoke unfurled, more buoyant than fog. After the olive trees were pruned, the branches were burned—daily smoke sacrifices in the face of a parasite infestation that threatened the harvest. Perhaps the stokers stood in the groves by their fires, shading their eyes with their hands, looking to see which columns of smoke rose in what way. All was blanketed in a mild burning smell.