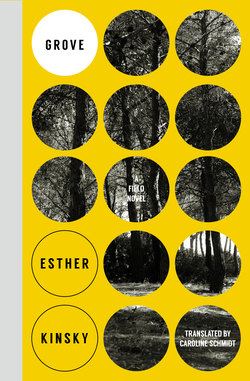

Читать книгу Grove - Esther Kinsky - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCemetery

IN THE EARLY MORNINGS I would walk the same route every day. Up the hillside, between olive trees, curving around the cemetery to the small birch grove. The two kiosks with cheerful-colored greenhouse flowers and garish plastic bouquets weren’t open yet. The municipality workers, busied since my arrival with thinning out the cypresses that had grown into one another, arrived in a utility van and unpacked their tools. The roadsides were littered with debris from the felling: sprigs, cones and pinnate, scaly leaves. Beside the cemetery entrance larger tree clippings piled up, thrown together sloppily and interspersed with stray tatters of plastic bouquets: pink lily heads that refused to wilt, yellow bows. Seen from here, the house on the hill lay between the village in the background on the right, and the cemetery in the foreground on the left. A different order. The village, quiet in the blue-gray morning light. Behind the cemetery wall the men called loudly back and forth to one another.

From the birch grove I looked onto the village and the cemetery; in the mornings not a sound from there reached this spot. I could see only white smoke past the wall and a row of ascending cypresses. Tree remains were being burned. The arborists were not yet felling. They first brought their small sacrifice. They must have stood there watching the fire. When the smoke thinned, the first saw revved.

In the afternoon I visited the graves. Both flower kiosks were open. On the left fresh flowers were for sale: yellow chrysanthemums, pale-pink lilies, white and red carnations. The kiosk on the right offered artificial flower bouquets with and without ribbons, hearts, little angels and balloons of various sizes. The woman selling flowers at the kiosk on the right was occupied with her phone for the most part, but occasionally cast me a sullen, mistrusting glance.

I searched for a term for the grave walls that made up a large part of the cemetery. Stone cabinets with small plaques, mostly bearing the name and a photo of the deceased, rendered on ceramic. Rocchi, Greco, Proietti, Baldi, Mampieri. The names on the graves were the same as those above store entrances and shop windows in the village. The walls are called columbaria, I learned, dovecotes for souls. Later someone told me the grave compartments are referred to in everyday language as fornetti. Ovens, into which the caskets or urns are slid.

The cemetery was always busiest in the early afternoon. Young men above all fulfilled their duties as sons and grandsons then; they would race in, jump out of their cars, slam the doors and slide rattling ladders up to their fornetti, in order to trade wilted flowers for fresh ones, wipe off the photographs, check the small burning lights. Old men scuffled by the grave walls, exchanged greetings, carried wilting bouquets to the trash and filled the vases with fresh water for the flowers they had brought with them.

In front of each fornetto was a small lamp, evoking an old petroleum lamp, or a candle, or an oil lamp like in The Thousand and One Nights. The lamps were hooked up to electric cables which ran along the lower edge of each tier of the grave walls, and burned at all times. Lux perpetua, someone explained to me. Everlasting light. In daylight their faint glow was barely perceptible.

On rainy days I would stand by the window, not wanting to go out. I fought fatigue brought on by the heavy, wet air. Sometimes the rain was mixed with snow. From the rear windows of my house, which faced north, on the low ground to my left I saw the new housing estates of Olevano, the road to Bellegra, the paved market place, the new school and the sports field, all lying between the cobbled-together, angular new construction and the hillside too steep to develop, with its narrow sheep pastures and a holm oak forest.

Above on the right was the cemetery, a darkly framed stone lodge with a view out onto the ripped-open valley. From their lodge, the dead could watch how ambulances were cleaned at the foot of the hillside, while paramedics made phone calls and smoked; how Chinese merchants set up their booths on Mondays, in order to sell cheap household goods, artificial flowers and textiles; how soccer games took place at the sports field on Sundays. Whistles and calls would echo from the hillside during soccer games, and the dull-green ground glistened in the rain, while old women on the steep path up to the cemetery slowly carried their umbrellas through the olive groves.